What is an artist? It’s a big question, and probably a silly one, but I ask it because an exhibition has opened at Buckingham Palace, in the Queen’s Gallery, that provides us with a spectacular hoard of material with which to attempt an answer.

It’s a show about how artists are portrayed. How they see themselves. How you can recognise one in the crowd. All the work on show deals in some way with the image of the artist. And because the Royal Collection is so rich in unexpected examples (different monarch, different tastes), it’s an event that keeps you on your toes as it skips hither and thither in the hunt for its quarry. The quarry, meanwhile —Rembrandt, Rubens, Leonardo, Dürer — refuses to be caught. Artists are slippery beasts at the clearest of times. When they are dealing with their own image, they are especially slippery.

Among the first faces we see is David Hockney — sunny, cheeky, cocky David Hockney — who, having been appointed to the Order of Merit, presented the Queen with a self-portrait so glum, it belongs on the face of a cancer surgeon. A few drawings later, the great Bernini, the most talented, skilled and thrilling sculptor of the baroque age, shows himself at the age of 80, looking like a character out of Dickens. Straggly hair. Wrinkly face. If you asked him for a rise, he’d go: “Bah, humbug!”

The point is, when it comes to themselves, artists cannot be trusted.

As they sit there staring into the mirror, trying to record what they see, they invariably see what isn’t there. Look at Rembrandt. The Royal Collection has a splendid self-portrait painted in 1642, when he was at the height of his career. On his head, there’s a huge black bonnet of a type more usually found on the heads of 15th-century dukes. Dangling from his ear is a piece of bling Elton John might envy. Across his chest, two thick gold chains signal a badge of office that he never held. Yet look how bluntly honest it all feels, how forthright his stare is. All this intense sincerity devoted to a fraudulent identity.

With artistic make-believe so thick on the ground, I found myself searching for moments of genuine honesty, rather than the pretend variety. Unexpectedly, I found one with Rubens, who, in a marvellous scrap of self-portraiture scrawled quickly onto a corner of a page, shows himself podgy, ageing, rheumy-eyed. You can imagine him startled by his own appearance in a mirror, and needing quickly to jot down the disappointment. Across the room, a pair of delightful self-portraits by the brothers Annibale and Agostino Caracci, done when they were still in their teens, have the same fresh air of quickly recorded truth. In baroque Bologna, a pair of local ragazzi are showing off their drawing skills. Today, they’d be challenging each other at keepy-uppy.

I am giving you the impression that this is a show about self-portraits. It isn’t. It’s a show about how the artistic identity evolved, how it was defined in art, and the visual language used to signal it. As aesthetic territory, it’s complex and confusing, and if you add to this innate complication the wildly different collecting tastes of the various royals who created the Royal Collection, you have a show that feels as if it keeps changing direction.

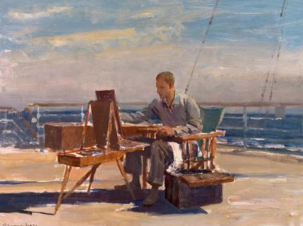

Having tackled the relatively straightforward issue of self-portraiture, we career next into the adjacent but hardly succedent territory of how artists are shown at work. What signals that they are artists? Sometimes the answer is banally obvious, as when Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun paints herself standing at an easel, brushes in hand, starting a portrait. Elsewhere, more interestingly, it’s something we have to intuit.

In a marvellous double portrait with his wife, Joos van Cleve, that odd presence in the Flemish Renaissance, shows himself with his hand twisted into an uncomfortable position. Weird. What’s he doing? Actually, he’s mimicking the action of holding a palette. The hand is there, in the right place, but the palette isn’t.

Savoldo, meanwhile, that odd presence in the Venetian Renaissance, shows himself from the top and the sides in a lop-sided pose achieved with mirrors.

No brushes. No palettes. The only evidence the sitter is an artist is the pose itself, which refers to the arguments raging during the Renaissance about the superiority of painting over sculpture. Painters can present the figure in the round in a single view. Sculptors cannot.

As the exhibition fast-forwards into the Victorian age, the exquisite complexity of Renaissance thinking gives way to lowlier ambitions. Landseer, the nation’s leading animal painter, shows himself drawing while two watching dogs assess his work. With his big whiskers and fluffy moustache, he looks as if he might have a chance at best of breed himself. Only in the Victorian mind could such a ludicrous image of an artist pass for something serious.

Thus we hop between epochs, tastes and themes as the show clings chaotically to the coat-tails of its artists. Some will find the frequent changes of direction annoying.

I found them stimulating. Tasked with arranging the wild lurches of the Royal Collection into straight lines, the Queen’s curators are, in my estimation, some of the most skilled and creative around.

And, of course, they have such diverse treasures to work with. Pottery types, for instance, will find much to enjoy in the precious Sèvres tea set featuring portraits of the great artists. Pour your darjeeling out of Michelangelo. Sip it from Raphael. Sweeten it with Poussin.

All that is fun, and very Royal Collection. But I’m a pictures man at heart, and it is among the pictures that the real pulse-quickeners are gathered. Chief among these is Artemisia Gentileschi’s portrayal of herself as La Pittura — the embodiment of painting. Acquired by Charles I circa 1638, when Gentileschi was working in England, it is the exhibition’s masterpiece, a picture in front of which I would happily be cemented for the rest of my mortal journey.

The fact that it is the vision of a woman artist is merely the most obviously exceptional thing about it. There’s so much more. The pose she adopts is spectacularly original. What devilish arrangement of mirrors was needed to look down on herself from these acute angles? See, too, how fresh the paintwork is, how lively the capturing of the fabrics and the flesh. Amazingly, the bare canvas she shows herself embarking on is just that — bare canvas. Here is an artist in the 1630s employing visual strategies that are centuries ahead of their times.

Palette in one hand, brush in the other, Artemisia is both the embodiment of painting and an utterly tangible human presence. Her hair is dishevelled. From her neck flops a pendant with an image of imitation. All this is prescribed in the iconography books as the symbolism of La Pittura. But there’s also an important difference.

In the symbol books, Pittura is always shown gagged, because painting is silent. Here, however, Artemisia, this fleshy, powerful, gorgeous force of nature, dispenses with the gag. It would be an affront to her reality, you feel, a lie she cannot tell.

Portrait of the Artist, The Queen’s Gallery, London SW1, until Apr 17