The first name that sprang to mind as I toured the V&A’s rousing and pertinent excavation of the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s was, of all people, Keith Vaz. The connection was prompted by a niche in the show devoted to Christine Keeler and the Profumo affair. Inside the niche were the famous chair, based on a design by Arne Jacobsen, that Keeler straddles in that provocative naked portrait of her, and the contact sheet from which the photographer, Lewis Morley, chose her riskiest pose. Also there were the pages of the Daily Mirror detailing the scandalous relationship between the war minister and the showgirl, and a collage of hypocritical headlines regretting the sexual shame, the human failing, the letting down of the nation. It’s all horribly familiar.

Of course, Profumo was a Tory minister, a breed of whom we expect sex scandals. And Vaz is not. But the bigger point here, the point the show ahead keeps trying to make, is that the 1960s invented all manner of attitudes and behavioural patterns that remain relevant, either because they continue or, more interestingly, because they do not.

One thing the Swingies are not is unfamiliar. Thus, the present show — entitled precisely You Say You Want a Revolution? Records and Rebels 1966-1970, though the actual timescale covered is groovily organic — is brusquely determined to describe a different epoch from the one we know so well. Fear not, Beatles fan. It doesn’t happen immediately. At the entrance, they give you some headphones that blast out a fabulous soundtrack that continues all the way through — the Animals, Barry McGuire, the Stones, the Small Faces. This alone is worth the entrance fee. It’s not often you’ll see Waldemar Januszczak busting out his moves on a gallery tour, but the moment We Gotta Get Out of This Place cranked up, I was hitchhiking left and right like a bespectacled chubby on Top of the Pops.

Also at the entrance, a row of album covers borrowed from John Peel’s collection tempt us with the promise of Motown, Dylan, the Grateful Dead. In this scholarly context, it’s more obvious than usual that the art of the album cover offered something unconfined and intrepid. Playing around with typefaces, styles, looks, the first wave of cover artists plunged greedily into the global goodie shop, following the new rule that there were no rules. The results have a mood of fearless exploration that you only get at the start of artistic journeys.

The show ahead is sprinkled thickly with the best results. There’s a full-size recreation of Sgt Pepper, featuring the original costumes sported by John and George — Paul and Ringo wouldn’t lend! There’s Andy Warhol’s banana for the Velvet Underground. And that fabulously spacy hologram for Their Satanic Majesties Request, the druggiest Rolling Stones album, inspired subversively by the directive found on every British passport that Her Britannic Majesty Requests…

So far, so predictable. We know about 1960s fashion, music, faces, album covers. But, having softened us up with irresistible Sixties fare, the show begins to grow glum. In fact, it spends the rest of its length becoming denser and darker. I have always understood these years as an explosion of hope. Hurrah. The 1950s were over. But that is not how they are understood here. Instead, we are confronted with a catalogue of dashed dreams.

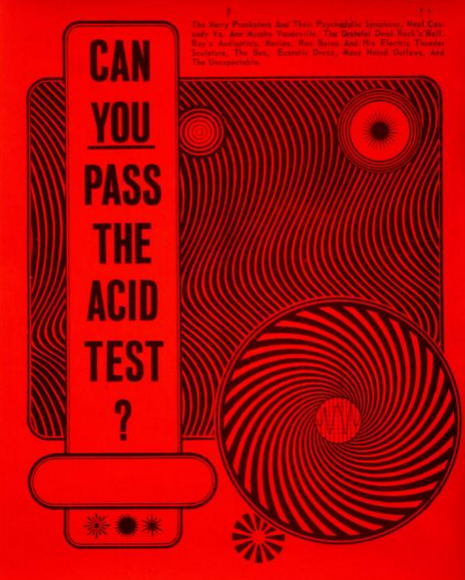

It begins in a section devoted to LSD and the expansion of the mind. For legal reasons, the organisers were unable to include actual tabs of acid in their drug moment, but they evoke it well enough with a feast of psychedelic posters, Pink Floyd on the soundtrack and some busy niches filled with stuff about Timothy Leary and Ken Kesey. Leave lots of time to peruse it all. The show is packed with texts, documents, photos and archives. The handwritten lyrics to Lucy in the Sky… are here. So is the passport given to George Harrison by his Indian guru, declaring him to be a citizen of Planet Earth. Stick that in your pipe, Your Requesting Majesty, and smoke it.

What is clear is that LSD and its mind expansions yanked the 1960s across the boundaries of legality. The drug busts that followed, the battles with authority, the street fighting in Paris and Kent State, can all be understood as attempts to force the genie back into the bottle. And all the time, the elephant in the corridor, the Vietnam War, prowled the perimeter, offering its murderous accompaniment.

Find time in particular to read the propaganda material collected by an American soldier in Vietnam, in which a calm version of the American truth/lies is compared with the searing and scary napalmed truth/lies of the Viet Cong. And while admiring the cute outfits worn by Pan Am stewardesses in this pioneering moment of transatlantic tourism, remember that the same planes with the same stewardesses in the same outfits were simultaneously transporting 19-year-olds from Idaho to Saigon.

Having descended into the underworld, herd-style, the show spends its second half darting in and out of the light. The point keeps being made how many of the telling features of life today started life in the 1960s. The first Apple computer, an unimpressively messy arrangement of solderings and circuit boards, assembled in his bedroom by Steve Wozniak, is presented as a tribute to thinking so far outside the box that it’s in the next cosmos, man. The first computer mouse is here, invented and fashioned out of an old bit of wood and a lightbulb by Douglas Engelbart.

In the show’s most spectacular space, the invention of festivals is celebrated with a surround-sound presentation of Woodstock that involves slumping down on a beanie bag and listening to the Mamas & the Papas. Mama Cass’s kaftan is on show as well: it’s extra extra extra large. The first environmental almanac. The Whole Earth Catalog. The birth of feminism. All were achievements of the 1960s.

But having drawn a vivid picture of a fiery and revolutionary decade in which so much was hoped for and achieved, You Say You Want a Revolution? says hello/goodbye to us on a mournful note, with John Lennon singing Imagine on the soundtrack. Lennon encourages us to remember how much was hoped for, but never happened. The point, you feel, is aimed squarely at our dismal present. We could have been this. We should have been that. But we aren’t any of them.

You Say You Want a Revolution?, V&A, London SW7, until Feb 26