That sad corner of the Edinburgh festival that deals with art has unsaddened in recent years. Where previously it seemed the Scottish art world was merely going through the motions in Edinburgh at festival time, grumpy at having to delay its summer holiday, there is now some evidence that the Edinburgh Art Festival is becoming as ambitious as it should be.

Flicking through this year’s thickish festival booklet, sardined with gallery entries, you might even imagine the city to be bursting with aesthetic opportunity. It isn’t. As always, the art contribution consists mostly of old shows, touring shows, regular shows and unrelated shows, all trying to sneak in under that big Edinburgh festival blanket. But something real is also stirring. A spirit of adventure runs through it. And, best of all, Edinburgh has lent it its architecture.

To experience it tangibly, track down the far-flung series of displays necklaced together under the title More Lasting Than Bronze. There are seven of them scattered about the city — by the docks, off the Royal Mile, down vicious stairs, up vicious stairs, a test for the thighs as well as a timely examination of the issues raised by the modern attitude to monuments. The title comes from Horace, who began his most plangent ode with the claim: “I have built a monument more lasting than bronze.” He was referring to the power of his words, the power of poetry, and how its impact can outlast the impact of metal or stone. By extension, Horace was claiming this power for all art.

His exhortation is timely because the recent anniversary of the First World War encouraged all of us to undertake acts of remembrance, and remembrance is what monuments are erected to prompt. At least, they used to be. These days, however, statues in squares have other ambitions. They are there to entertain, to cheek, to stimulate. The artistic antics on the Fourth Plinth in Trafalgar Square, for instance, are consistently tickling. But should we, a society that needs so often to deal with death and darkness in our daily world, avoid death and darkness so actively in our monuments?

Hiking through Edinburgh searching for events marked More Lasting Than Bronze is an adventure and a lesson. I blundered into a stony architectural cluster called the Old Royal High School with no idea what to expect. I was directed to a leather-benched lecture theatre, in which I was the only visitor and where sad voices were singing sad songs in a language I could not follow. It turned out to be Punjabi. The artist, Bani Abidi, had tracked down the ballads sung by the mothers of Indian soldiers sent to the front in the First World War, in which they begged their menfolk not to go. A beautiful sadness echoed through a beautiful space as it remembered a forgotten loss.

Personally, I have given up on the London art world ever finding enough emotional seriousness in itself to give us a public art that triggers memorial profundity as successfully as this. Look how sniffily the curatorial classes reacted to the poppies at the Tower of London. The London art world doesn’t do emotional truths. But the Scottish art world does.

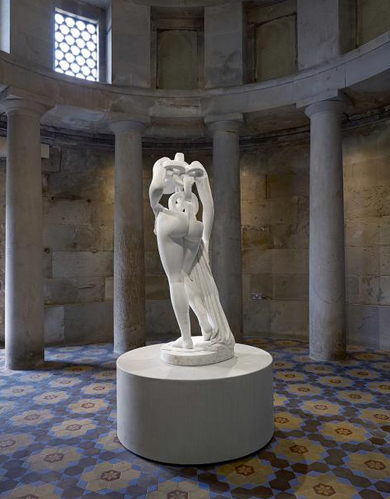

Up the hill, inside an unlikely monument to Robert Burns erected in 1831 that looks like a circular Greek temple, I encountered a new sculpture by the Edinburgh artist Jonathan Owen, in whom the age of neoclassicism lives on. Owen reconditions old statues. He cuts into the ancient marbles and replaces their former look with their newest one. In this case, he has taken a naked nymph — page one in the catalogue of classical statuary — and recarved her torso into a thick chain that slumps uselessly sideways. Time has been hacked. Brunel has taken up classical sculpture.

Connecting the Burns Monument with the valley below is a painfully steep stone staircase called, excellently, Jacob’s Ladder. The exhibition map directs you down it, and after a thigh-killer of a descent, you find yourself encountering the neon art of Graham Fagen, glowing eerily under a railway bridge. A skeleton. A boat. A beach. What is being remembered here? It turns out that Fagen’s neon records a voyage by Rabbie Burns to Jamaica in 1786, when he set off to work as an overseer of slaves on a sugar plantation. Under a gloomy railway arch, another dark past collides with a dark present. And Owen’s chained nymph at the top of Jacob’s Ladder begins to mean something more.

All this is superbly set and superbly plotted. The citywide search for meaning mounted by More Lasting Than Bronze sends you to Prince of Wales Dock to find the lighthouse supply boat that Ciara Phillips has dazzle-painted with words that glow only at night and say: Every Woman a Signal Tower. In the lovely Trinity Apse, an unexpected slab of authentic gothic in the foothills of the Royal Mile, Olivia Webb has recorded the poignant efforts of a New Zealand choir to serenade the victims of the Christchurch earthquake. Think Gareth Malone in a beret, with a tear.

Elsewhere, it’s a lucky dip. The best of the shows hitching a lift on the festival ride is Surreal Encounters, at the Gallery of Modern Art. Centred on the collecting story of the shape-shifting surrealist supporter Roland Penrose, whose personal collection was bequeathed largely to Edinburgh, this firework of a show features the finest spread of surrealist art — paintings and objects — to be seen in Britain since the momentous Surreal Things: Surrealism and Design show at the V&A in 2007. Dali, Picasso, Ernst, Miro, Magritte — especially Magritte — they’re all here, with impressive examples in impressive numbers.

I was less pleasured by the thick sludge of drawings by Joseph Beuys that has arrived across the road in the other half of the Gallery of Modern Art. Having lived through the era when every second show in Europe seemed to be of Beuys, I feel I have seen enough of his shamanic blunderings to last several lifetimes. Beuys cannot be made sense of. He speaks through textures, materials, half-truths, half-myths. It works on a grand scale in his installations and sculptures. But drawing is a medium for saying things more precisely. Too much here is a brown mess.

Back among the festival treats, a journey to Jupiter Artland thrusts us deep into the West Lothian countryside, where art has bloomed mysteriously among the forests and the lakes. If you’ve already been there, you’ll know that Artland is a cross between a sculpture park and an adventure playground. As you yomp along its winding trails, you encounter unexpected art sights: an opening to the centre of the earth by Anish Kapoor; a sobbing Gretel lost in the woods by Laura Ford.

For this year’s festival, Christian Boltanski, the much exhibited French memorialist, has imported sighs and sobs into the park. On a small island in a small lake, Boltanski has planted a fragile display of tinkling Japanese bells attached to the tops of swaying stems that move with the wind. Apparently, the stems and bells reproduce the map of the stars on the night he was born: September 6, 1944. The fact that the island and its tinkling bells are across the water, over there, out of reach, seems to mimic the feeling of a distant memory that you cannot fully recall.

At the Fruitmarket, the Mexican sculptor Damian Ortega is attempting to transport the moods of Oaxaca to the environs of Edinburgh station. It’s a struggle. Working in primitive clay, left usually in atmospheric blobs though sometimes formed into the sun-dried bricks from which the Aztecs constructed their pyramids, Ortega quotes too obviously from his ancient Mexican surroundings. The results feel perversely touristic, as if he has studied his own culture from an open-top bus.

I wanted to write about a show at the Dovecot Gallery enticingly entitled The Scottish Endarkenment. But when I got there, an attendant stormed across the floor to stop me taking photos of any exhibits. As there was no catalogue, I needed them as an aide-mémoire. But apparently I was infringing “copyright issues”. Welcome to the Scottish endarkenment.

Edinburgh Art Festival, various venues, until Aug 28; edinburghartfestival.com