Has performance art grown too safe, too middle-class? I ask the question because it used never to be either of those things. When Chris Burden nailed himself with outstretched arms to the back of a Volkswagen in 1974, in perverse imitation of Christ, he was not being safe. When Vito Acconci lay on the floor of the Sonnabend Gallery, in New York, in 1972 and masturbated continuously for eight hours a day, he was not being middle-class — even if you include judges.

No. In its earliest manifestations, performance art was scary, visceral, rude, wild, revolutionary and definition-testing. But, given how popular it has become in curatorial circles, is it still seeking to épater le bourgeois?

The blunt answer is, no. Not in most cases. Traipse round Tate Modern’s expensive new extension, devoted principally to performance art and its derivatives, and you will find nothing that offends your mum or savages you subcutaneously. At today’s Tate Modern, visitors are counted, not challenged. In most contemporary-art situations, performance art’s role is to eat up lots of visiting time with gentle experiential tickles.

What a relief, therefore, to encounter the work of Ragnar Kjartansson at the Barbican Art Gallery. Described in the pre-publicity as “the world’s finest performance artist”, Kjartansson, who is from Iceland, may actually be the world’s finest performance artist. He’s certainly tangy, exciting, inventive, visually intoxicating and, yes, obsessive and unsafe.

The show’s opening performance, called Take Me Here by the Dishwasher: Memorial for a Marriage, has you wandering into a scene of memorable squalor. Thrown onto the floor is a collection of soiled-looking mattresses, surrounded by empty beer bottles, across which are slumped 10 unkempt guitarists who look as if they were discovered in the doorways of Camden, begging for 10p pieces to spend on ketamine. Long-haired, blank-faced, they ooze depression and boredom as they endlessly strum the same tune on their battered guitars. And that’s when the magic happens.

The scene may look like something Tracey Emin discarded for her unmade bed — on the grounds that it was too squalid — but the melody emerging from the simultaneous strumming of the down-and-outs is so haunting and beautiful that it lifts you out of the Barbican and deposits you on a glacier in a forest on a mountain in some faraway Icelandic love saga. Composed by Kjartan Sveinsson, formerly of the Icelandic indie band Sigur Ros, the haunting Nordic chorus ought to be describing the feelings of a Brünnhilde for a Siegfried. Instead, the subtitles tell us, it records the lust of Ragnar’s dad for Ragnar’s mum, and the naughty things they got up to by the dishwasher. A helpful video, projected onto the walls, bluntly illustrates their spurty kitchen antics.

Apparently, the work commemorates Kjartansson’s conception. His parents were both actors, and a family legend has it that Ragnar was conceived live on set during the making of a movie in 1975. It’s a nice bit of extra info. But what makes this performance work so well is the sensuous intermingling of squalor and beauty. The grubby cast of down-and-outs, and the heavily beer-bottled environment in which they slump, ought to be the setting for a depressing kitchen-sink drama. If a British performance artist had created this, it surely would have been. Here, though, the continuous accompaniment of the haunting Icelandic melody enables a transformation to occur. Cinderella goes to the ball. An orchid grows on a rubbish tip. Enlarged by the angelic chorus of love, the passion of Ragnar’s dad for Ragnar’s mum ceases to be domestic and furtive, and floats up into the Barbican eaves, where it becomes something eternal and rousing.

Born in Reykjavik in 1976, Kjartansson studied painting at art school and, like so many of his generation, harboured parallel fantasies of becoming a musician. Music features prominently in most of his works. So, too, does a sulky desire to belong to a previous century.

If you are lucky enough to catch the performance that takes place on the Barbican lake at weekends, in which two dreamy girls in Edwardian costumes float across the water, locked in an unbreakable kiss, you will recognise moods that belong in an Ibsen drama or a painting by Arnold Böcklin: which is to say, northern moods that are simultaneously romantic and hopeless.

Outside the Barbican, above the main entrance, a huge neon sign informs us that Kjartansson has called his show Scandinavian Pain. Cheeky bugger. He is both teasing us about our appetite for Nordic noir and promising us further helpings of it. All the way through this engrossing retrospective, as it switches from performance to film to painting, big Nordic moods with a heroic ring to them get mixed up with the beery, faggy textures of the modern world and manage, usually, to apotheosise them.

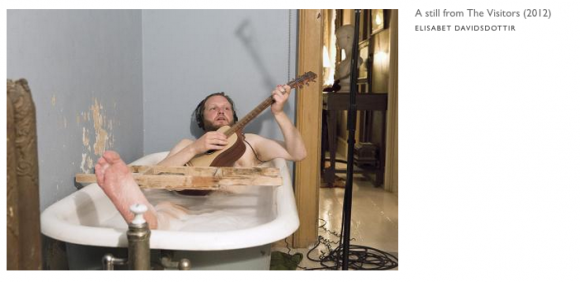

The Visitors, from 2012, is a huge film piece set on nine screens simultaneously. Each screen features a different room in a large, rambling Victorian mansion, in which a chamber orchestra of contemporary musicians — pianists, cellists, guitarists, banjoists, flautists — has gathered for an ensemble performance. As it unfolds across the nine screens in real time, Big Brother-style, the piece flicks between episodes of dreamy boredom that are curiously fascinating. Who is the naked woman with her back to us in the bed next to the guitarist? Why does the angsty cello player in the droopy dress look like someone out of a pre-Raphaelite painting? As the music slowly unfolds, the quotidian questions die down and a transportation commences to ethereal realms.

I read that The Visitors was inspired by an Abba record of the same name. It was the band’s last album, recorded while their interpersonal relationships were falling apart. Something of this sense of fracturing has survived the transition into a performance piece. As the singers in Kjartansson’s mansion chant their lonely chorus of “Once again, I fall into my feminine ways”, everything grows increasingly edgy, fragile and melancholy.

Unlike many lesser performance artists, Kjartansson pays extreme attention to his visuals. Ultimately, they are what lingers. The fin de siècle mansion in which The Visitors unfolds is a perfect mix of decrepit and romantic. An earlier film piece, playing upstairs, features a popular Icelandic actor called Laddi, who wanders about in the snow, firing a rifle at nothing in particular. Laddi is dressed in black. So the surrounding snow turns him into a nihilistic shadow puppet whose hopeless gun campaign seems to be saying something stark on the subject of life’s ultimate pointlessness.

The darkest work here features Kjartansson’s mother, of all people, whose theatrical past enables her to spit repeatedly in her son’s face, in a startling performance piece called Me and My Mother, filmed in front of the same background at five-yearly intervals since 2000. He looks at us, she spits at him. Look, spit. Look, spit.

Has performance art grown too safe, too middle-class? Not in Iceland, it hasn’t.

Ragnar Kjartansson, Barbican Art Gallery, London EC2, until Sept 4