There has been a shift in art in recent years towards abstraction. Unlike some of art’s shifts, it has not grown into an avalanche. Not yet, at least. But the rumblings have been loud and unmistakable. Abstraction is back.

It’s a surprise because it had a stake driven through its heart in the 1980s, and I for one never expected to see it return. When art adopted the cut-and–paste preferences of the internet world — figurative, glossy, packed with logos and soundbites — there seemed no space left for something as un-poppy and languid as abstraction.

Yet a quick perusal of the art calendar this month sees abstraction shows springing up everywhere. At Parasol Unit, they will soon be opening the first British survey devoted to Rana Begum, a Bangladeshi abstractionist who paints subtle and inch-perfect geometry onto sheets of mild steel. At Megan Piper’s new space on Jermyn Street, there’s a show of works by Tess Jaray, the veteran British abstractionist (b 1937), whose minimalist paintings are a response to baroque architecture. At Greengrassi, the especially inventive Tomma Abts is creating abstract hybrids like none that have existed before.

Now, all these abstractionists are women. It could be a coincidence. But what if it is not? What if something in the current revival of abstraction is answering a distaff need for an art filled with possibilities: with less prescription and more subtlety; fewer words and more sights?

My first stop on an adventure tour of contemporary abstraction was the Whitechapel Art Gallery, where Mary Heilmann, another veteran female presence (b1940), is being treated to her first British survey. She’s from San Francisco, which is also unusual, as there’s a tangible divide in American art between West Coast and East Coast. Put crudely, East Coast art is taken more seriously than its opposite. Put even more crudely, New York is for artists, San Francisco is for hippies.

It’s a prejudice that, rather surprisingly, finds itself illustrated perfectly by this messy and disappointing event. Heilmann studied literature first, in Santa Barbara. Then poetry and ceramics in San Francisco. Then ceramics and sculpture at Berkeley. It’s a CV that tells you she has always wanted to be a creative, but also that her creativity has always been all over the place.

These days, she’s primarily a painter who also designs coloured chairs to dot about her shows. The opening sight here is a set of grid paintings from the 1970s, in which the black lines have been scratched with a finger into red backgrounds, a technique inspired, I read, by Heilmann’s work with children in her teaching days.

Grids are grids for a reason. Their role in art is to create precise minimalist patterns so that a sense of perfect order can prevail. Think of Mondrian, Malevich, Agnes Martin. Creating them with school fingers gouged into blobs of acrylic is the artistic equivalent of making a soufflé on a campfire.

Heilmann’s training as a ceramicist is another messy influence on her progress. Enamoured of the beauty of coloured glazes, she is happy to bash out blobs of inchoate clay and to allow the coloured surfaces to shoulder all the creative responsibility. Unfortunately, a blob will always be a blob. And no blob in the world has ever been the perfect setting for an exquisitely coloured glaze.

Whether she’s making paintings or ceramics, drawing sketches or making chairs, Heilmann’s enthusiastic sloppiness gives her output an evening-class air. It’s an impression heightened by the intrinsic quickness of the acrylic paints she favours. Acrylics, so popular in the 1960s and 1970s, are a fast way of painting abstracts: too fast. They dry to a thin surface that never feels as profound as it pretends. In the hands of a master — John Hoyland springs to mind — acrylics can indeed be made to feel deep and mysterious, rather than scratchy and plastic. But that doesn’t happen here. Trying her hand at thunderous abstract expressionism, as with the billowing Crashing Wave (2011), Heilmann makes pictures whose drama looks as if it came from a mail-order supplier.

And that’s not the end of the bad news. Too often, too easily, she borrows too obviously from her gaudy Californian surroundings. Inspired by Mexican rugs, she paints pictures that look like Mexican rugs. Inspired by pueblo houses, she paints pictures that look like pueblo houses. The recent rediscovery of “forgotten” women artists has been valuable and successful. But it can lead to the overpromotion of small talents. That, I’m afraid, is what is going on here.

It is not, however, what we see in the Tess Jaray show at the Megan Piper gallery. Piper has smartly carved a niche for herself as a dealer who works exclusively with artists with long careers behind them, but who are currently undervalued. It’s a smart move, because older artists have big back catalogues, and if you succeed in reappraising them, you’re quids in.

Jaray is from the other end of abstraction’s rainbow from Heilmann. Working precisely with exact minimalist measurements, she paints exquisite arrangements of grids and rectangles that usually have a twist to them. Here, the chalky Georgian shades of pale grey and eggshell blue are divided by a jagged line borrowed, apparently, from the baroque balustrade created in Rome at the church of San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane by Francesco Borromini. It’s a subtle but beautiful borrowing that whispers big ideas from the wings, like a prompter at a play.

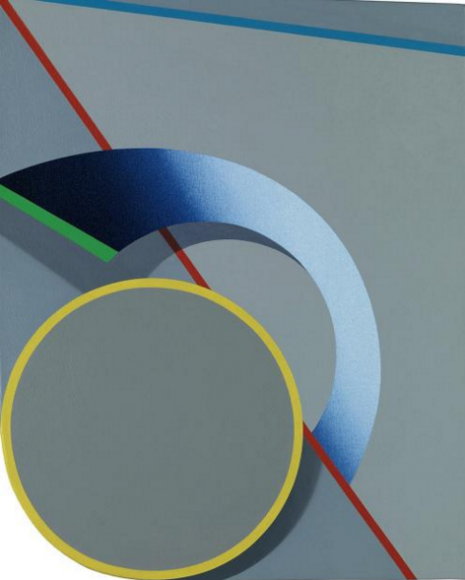

Although the German-born Tomma Abts won the Turner prize in 2006 for her brilliant and brilliantly puzzling contributions to abstract art, she has since kept a low profile. Her shows are rare. She’s never in the news. Her exhibition at Greengrassi is her first London display for five years.

As always, the pictures are tiny and on identical canvases (48cm x 38cm), creating the immediate impression of a carefully plotted project. Only when you lean in and let them speak to you individually do you begin to appreciate how much mad variety there is in them. Some are as jagged as panes of broken glass. Others are floaty, spacey, cosmic.

What’s really different is the range of visual sources that are being mined: there aren’t any! At least, none that are easy to recognise. Most abstraction ends up reminding us of something. It can be something from the natural world, like Heilmann’s billowing waves, or something architectural, like Jaray’s Borromini tributes. But Abts’s pictures have a strikingly independent presence. It’s as if the varied sights before us have been created out of thin air by a new type of artistic technology.

Here and there, there are hints of a corporate logo or a snappy brand identity. But in the main they remind you of nothing you have seen before. The contemporary world is being treated to a contemporary abstraction that suits it perfectly.

Mary Heilmann, Whitechapel Art Gallery, London E1, until Aug 21; Tess Jaray, Megan Piper, London SW1, until Fri; Tomma Abts, Greengrassi, London SE11, until Sat