The butterfly in art: now there’s a subject. All manner of animals have crept, slithered, raced, flown and charged onto art’s great stage — the poor old snake will always stand for Satan; St Jerome will always be accompanied by his lion — but among these busy symbolic presences, the butterfly’s role has always been especially profound. Butterflies may be tiny, fluttery and paper-thin, but their lot in art is to stand for stuff that is huge, weighty and problematic.

To the ancient Greeks, they were manifestations of the human soul. That’s what Aristotle believed. The ancient Greek word for a butterfly, “psyche”, was also the ancient Greek word for the soul. At the other end of time’s rainbow, at our end, Damien Hirst’s butterfly pictures, made with real butterflies mimicking the appearance of stained glass, are a morbid reminder of life’s ultimate uselessness. And what are Gainsborough’s daughters chasing in that sad and lovely painting of them in the National Gallery? A butterfly, that’s what. A pale, fluttering, ghostly cabbage white.

So the butterfly is a crucial presence in art, and in unveiling for us the astonishing career of Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) — butterfly painter extraordinaire, fearless traveller, curious mystic — the Queen’s Gallery has added something valuable to a pictorial tradition that was already full of wonders.

Merian was the daughter of the excellent Swiss engraver Matthäus Merian, who produced the finest early set of topographical views of Germany. After he died, in 1650, his widow married the equally celebrated still-life specialist Jacob Marrel, who taught Maria Sibylla how to paint flowers, butterflies and caterpillars. So her training was world-class, and it predisposed her to capturing the wonder-filled world of nature in exquisite detail.

We catch up with her here painting a bouquet of Provençal roses, those pretty Dutch hybrids packed with layers of pink petals that are notable, also, for their scent. Renoir himself, in his porcelain-painting phase, could not have bettered the pink and dreamy bewitchment of Merian’s roses. You don’t just see them, you smell them.

This is supposed to be a show about butterflies, but it is also a show about plants, flowers, leaves and fruit. As a child, Merian kept silk moths, and it was while watching the transformation of egg to caterpillar to chrysalis to moth on a branch of willow that she developed the fascination with metamorphosis that became her signature concern.

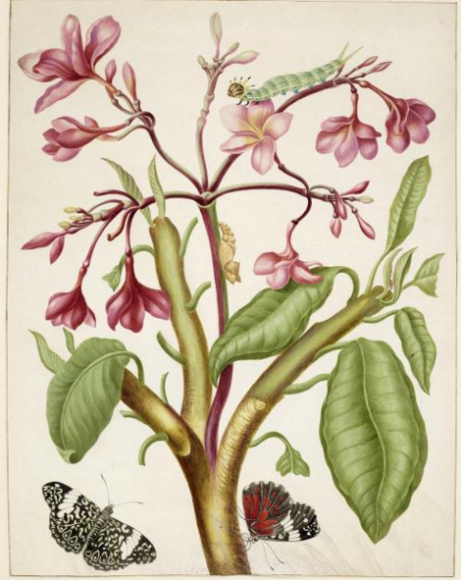

For Merian, it was never enough to paint the final insect. She wanted always to tell the full story of its creation. When she painted a red underwing, that exciting moth with the red flashes that also feeds on willow, she added its eggs, its caterpillar, its chrysalis and some visiting puss moths, too. What we’re getting isn’t just a picture of a moth, it’s the encapsulation of a life cycle with a sense of the miraculous about it.

All this is happening at the end of the 17th century, when most viewers of her work would still have believed that life was a spontaneous creation by a divine force: that butterflies came from nowhere and caterpillars were a different species. Her ripostes to those views are always beautiful and precise, but they have something else about them, too: something I’m going to call spirituality, because I cannot think of another word. It’s a fascination with the natural world that feels as if it has the underlying ambition to understand deep religious truths.

The continuing facts of her life bear this out. Having married one of Marrel’s pupils, she had two daughters, both of whom became her apprentices. In 1685, she parted from her husband and settled in Holland, where she fell in with the Labadists, a curious religious grouping who believed in extreme piety, fasting, giving away your possessions and the lawfulness of a separation from an unconverted partner. This last belief must have been especially appealing. In Amsterdam, she worked her way into the company of a pioneering generation of natural-history collectors, who would wait at the docks for exotic new specimens to arrive from the Dutch colonies scattered about the world. The thriving market for natural wonders triggered a thriving market for illustrations of them. It was into this market that Merian pushed herself with her love of natural detail and her fascination with metamorphosis.

In 1699, she took the remarkable decision to travel to Suriname, the most exotic of all the distant Dutch colonies. The Dutch had acquired it from the British under the Treaty of Breda in 1667, in exchange for an unwanted settlement called New Amsterdam, now known as New York. The Labadists had a branch in Suriname, and Merian voyaged there in her early fifties, to continue her gorgeous exploration of the cycle of creation.

The Suriname pictures are the spectacular heart of the show. When it came to exhilarating colours and extravagant shapings, the lepidoptera of Suriname were of an entirely different order from the sensible grey beasties of Holland and Germany. See that huge sheet of bright blue paper swirling around a pomegranate branch? That’s not a sheet of paper, it’s the menelaus blue morpho, drawn to size. As with all her butterflies, she shows it from one angle with its wings open. And from another with its wings folded. Below is the caterpillar. Below that the chrysalis.

Where Holland was flat, wet and grey, this new world was vivid, colourful, sun-drenched. Merian’s picturings of it, scientifically courageous though they were, feel also as if they feed directly into the paradise myth. Whatever paradise was, and wherever it was, it must surely have looked more like the colourful world evoked by her now than the one she had left behind in Amsterdam.

The book she published on her return is one of the greatest of all natural-history books. Long before Gould and Catesby, a woman from Amsterdam was illuminating the wonders of the insect world with a combination of precision and poetry that was her trademark. George III bought not only the book but, more adventurously, an almost complete set of her coloured drawings for it, painted on vellum to make them particularly bright. Both are here.

Later, there were grumbles about her inaccuracy. As a pioneer, she could hardly help but make the occasional scientific blunder. To illustrate the origins of the lanternfly, an extraordinary insect whose head mimics the appearance of a baby crocodile, she planted the top of a lanternfly onto the bottom of a cicada, creating a weird hybrid that could never have existed.

Scientists may tut, but I love these mad swervings from the facts. Merian’s intoxicated jungle art does something pure science could never do: it captures not only the look of things, but the dumb excitement triggered in us all by nature and its wonders.

Maria Merian’s Butterflies, Queen’s Gallery, London SW1, until Oct 9