The first time I came into contact with Shaun Greenhalgh I had no idea I was doing so. Unfortunately I was on national television at the time, talking about the French post-impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, blissfully unaware that I was making a fool of myself in front of a couple of million witnesses. And that somewhere in Bolton, in a pub, Britain’s greatest forger was watching me and thinking to himself: “What a plonker.”

I am an admirer of Gauguin’s art and for the centenary of his death, in 2003, I persuaded the telly people to let me make a film about him. At the same time a big show opened in Amsterdam, in the prestigious Van Gogh Museum, telling the story of the wild weeks that Van Gogh and Gauguin spent together in the south of France before Van Gogh cut off his ear. The Amsterdam exhibition was brilliant: packed with important artworks borrowed from the finest museums in the world. I had to film it.

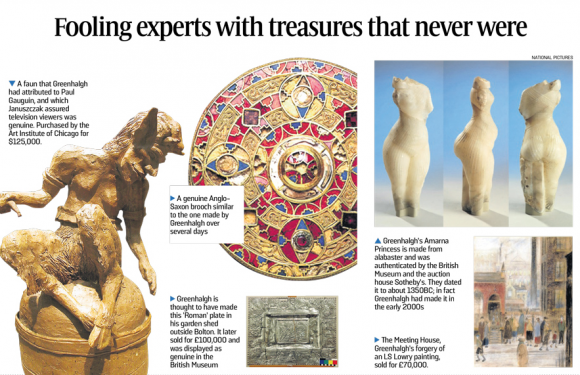

Sitting in a Perspex case at the start of the show was a sculpture by Gauguin that had been bought in the late 1990s by the Art Institute of Chicago. If you know your American museums, you will know that Chicago’s Art Institute is blue chip — one of the best collections in the world. It is where Seurat’s A Sunday on La Grande Jatte hangs, and a ton of Monets, Manets and Cézannes. The newly acquired Gauguin showed a faun, a mythological wood nymph that is half-man, half-goat, sitting impishly on a mound of clay.

The sculpture, which had not been shown before, was signed “PGo”, a cheeky shorthand signature that Gauguin sometimes used that was derived from the nautical slang for a penis. In his youth he had been a merchant seaman and had picked up various naughty nautical practices. I wanted to make a point about it, and the sculpture from the Art Institute seemed the perfect opportunity.

You can watch the encounter on YouTube. There I am, talking about the PGo signature, and speculating cleverly about the possible self-portraiture implied by the image of the naughty faun. Back in Bolton, meanwhile, Greenhalgh, who had made it a few years earlier and lost track of it, was interested to find out that it had now been acquired by the Chicago Art Institute and that the museum had paid $125,000 for it.

It was not until I opened a newspaper one morning in 2006 that I saw The Faun again. There it was, lined up in a long row of photographic evidence that had emerged in court about a forgery ring set up in Bolton by the least likely forging supremos of all time — the Greenhalgh family. According to the newspapers, Greenhalgh, his father and his mother, both of whom by then were in their eighties, ran their ring out of a shed in the garden of their council house. Shaun made the fakes; his dad and mum sold them. That is what the newspapers were reporting.

Apart from the sheer unlikeliness of this arrangement, the most surprising thing to emerge from the court proceedings was the range of fakes the Greenhalghs had supposedly produced. They had made Assyrian reliefs, LS Lowry paintings, Barbara Hepworth ceramics, English watercolours and post-impressionist sculptures. Was there anything the Bolton forgers could not fake?

The newspapers reported that the three Greenhalghs were in it together, which is why they were able to produce so much. In fact they were a one-man band. Shaun made everything himself. As he makes clear in the remarkable memoir he wrote in prison it was Shaun, and only Shaun, beavering away in his shed in Bolton, who was the forger. His poor mother and father were roped in to help him complete some sales. But that was only after three decades of relentless pastiching had been and gone.

I got my hands on Shaun’s memoir by accident. In 2007, when the crown court in Bolton sentenced him to four years and eight months in prison, I fired off a quick letter to a couple of commissioning editors in television demanding to be allowed to make a film about him. This bastard had fooled me on British television, I complained. Too late, they replied. Someone else had got there before me.

In the end both Channel 4 and the BBC made separate programmes devoted to the “Artful Codgers”. Both were profoundly inaccurate. How inaccurate was brought home to me when I finally got round to reading the thick stack of typewritten pages that thudded onto my mat a couple of years later — A Forger’s Tale: the prison memoir of Shaun Greenhalgh.

He had been persuaded to write it by a researcher from another television company that also wanted to make a film about him — a biography. Nothing came of the project, except the memoir. Once he started, he could not stop. With nothing else to do in prison, it all came pouring out. How he made his first fakes when he was still in primary school. How Victorian pot lids were all the rage at the time and how, with the knowledge he had picked up in pottery classes, he was soon banging them out at a fiver a head. By the time he was in his teens he was earning more a month than most of his friends’ fathers.

At school in a Bolton comprehensive he gave up art classes after a couple of years and set about learning it all for himself. This was Bolton in the 1970s, where the dark satanic mills had turned into dark satanic ruins and where a precocious lover of art had little to encourage him. As the newspapers presented it, the Greenhalghs were a Bolton Cosa Nostra, a ruthless ring of Lancashire fakers who had set out to con the art world. But what they really were was a modest north of England family who had managed to spawn a boy wonder: a kid who could make anything.

Paradoxically, it was the Bolton Museum that saved Shaun by firing in him a fascination with all things Egyptian. He taught himself hieroglyphics. And stone carving. And the Egyptian system of proportions. Years later, when he got really good at carving, he sold an Egyptian sculpture of an alabaster princess to this same museum for £440,000.

This sculpture, the so-called Amarna Princess, had been pored over for months by all manner of experts in London and beyond. The damn thing fooled me as well — thanks again, Shaun — when it popped up alongside Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus in an exhibition at the Hayward Gallery celebrating 100 years of success by the then National Art Collections Fund. Now that I think about it, it did look a little clean.

How it was made is detailed in the memoir, including the startling information that Shaun dropped the piece of alabaster and had to glue it back together “with Araldite Rapid” when it cracked in two. The experts should surely have noticed that the Amarna Princess was carved out of a piece of stone that had been glued together. But they did not.

The Araldite Rapid came in useful as well for Gauguin’s faun, which was made in separate pieces and then stuck together in an entirely un-Gauguiny way. I did not see the glued-up bits either, but hey, it was in a Perspex case, and the lights were glary!

Not long after leaving school Shaun made his first Degas drawing. And successfully sold it in a big auction in London. He made Egyptian heads. And sold those. And studio ceramics in the style of Hans Coper. And gothic crucifixes. And watercolours of birds in the manner of Archibald Thorburn. Lots and lots of Thorburns. Then there was the Lalique glass. The Chinese pots. The Venetian bronzes. Easily bored, he kept changing styles, forms, materials, epochs, always getting as good as he could at every different technique. Then he would drop it and move on to something else.

It was this appetite for variety that led me to him, and him to me. I was making a television series about the Dark Ages, that much-misunderstood epoch when the lights of civilisation were said to have been switched off across Europe, and I wanted someone to show me some sophisticated Dark Ages manufacturing skills so that I could make the point that the Dark Ages were not dark. In Shaun’s court case it had emerged that he had produced several Visigoth eagle brooches, as well as various Anglo-Saxon artefacts, so he clearly was just the man for the job.

Tracking him down was difficult. Shaun keeps himself to himself. Since his release he had been working in jobs organised by the prison service and was collecting wheelie bins when I met him. The police had taken everything away when they arrested him, including his first school sculptures that his mum and dad had kept, as you do with your children. The Yardies snaffled the lot. But they could not take away all that deep and intense knowledge built up from 40 years of making things.

For our film, he produced an Anglo-Saxon brooch, made of silver and rock crystal, the kind of thing a noble might pin to his cloak. I was only interested in seeing roughly how it was done. But Shaun went all the way. First, he made an ingot, produced from exactly the right quantities of silver and mixings that the Anglo-Saxons would have used. Then he spent days hammering it into the right Anglo-Saxon thickness. Then he cut it up, engraved it, made the enamel inlay, shaped the rock crystal, fashioned a copper pin mechanism, put it all together and set about making it look 1,000 years old.

The last part I had not asked for. Indeed, it was not what I wanted. But old habits die hard and having knocked a few chips off the rock crystal he began opening and closing the brooch a thousand times. That, he explained, was how often it might have been used before it was lost in a field. He also deliberately wore down one of the evangelist engravings on the front because that was the part that would have been grasped by the thumb every time the brooch was put on.

I watched all this with pure fascination. I have met lots of impressive people in my life, but they have generally been impressive with their minds or their mouths, not with their hands. Shaun’s hands had magic in them. When he was making things, he became a different person. Gone was the shy and suspicious middle-aged van driver from Bolton, replaced by a technical wizard who darted this way and that, producing the bits for his brooch with myriad kinds of alchemy. In Anglo-Saxon times this would have been the work of 10 people. Now it was just him.

I should add that all this was going on in a garage in Bolton borrowed from Shaun’s sister, and that the garage had a low retractable door at the front on which he kept banging his head. If anyone makes a film of his life — which they should — it would be a mix of Billy Elliot and an Ealing comedy. With some F for Fake thrown in. How could anyone get this good at meticulous international forgery while growing up in Bolton in the 1960s and 1970s?

The answer arrived on my mat a few months later. Written on A4 pads in prison, Shaun’s story starts out as an attempt to explain his actions and correct the various inaccuracies that had been peddled about him and his family. But pretty quickly it becomes a runaway train of information about the things he made and how he made them. The court case, it turns out, had only scratched the surface of his output.

Having made his pieces, much of his most inventive effort as a forger went into giving them provenances, or as he prefers to call them in the book, “stories”. Among all the dodgy art world practices described here, nothing is quite as troubling as the creation of provenances. Without a provenance nothing sells. So Shaun needed to be especially inventive in coming up with his own. For the Amarna Princess a brief line in an old catalogue bought by post from a book trader was all it took to persuade the experts that his newly made Egyptian alabaster had a rightful past. Too many “provs”, warns Shaun, are “hardly different from a myriad tales you hear on the Antiques Roadshow”.

What, then, are we to make of his own contentious claims? The story of how he claims he made the drawing now known as La Bella Principessa, by Leonardo da Vinci, but which ought really to be called Sally from the Co-op, by Shaun Greenhalgh, is hilarious. Sally — whose real name was Alison — worked at the checkout in the Co-op where Shaun was also employed in the late 1970s. To draw her he says he bought an old land deed that had been written on vellum, and finding the “good” side to be too ink-stained to use, turned it over and drew on the rough side instead, as Leonardo would never have done.

It was never meant to be a da Vinci. But he did have some fun pretending he was left-handed. In a book about La Bella Principessa written by the distinguished Leonardo scholar Martin Kemp much is made of the left-handedness of the artist. But Shaun claims all he did was turn the drawing through 90 degrees when he did the hatching, and voilà. As for the wooden board to which the drawing is glued, that came from Bolton Tech. His dad worked there and when the college began throwing away unwanted desks he brought one home and Shaun reused the lid. To make it look older, he popped in some inconsequential butterfly joints, learnt in his woodwork classes at school.

Some Renaissance experts will not need Shaun’s book to tell them La Bella Principessa is not by Leonardo. She has been triggering grumblings ever since she popped up in auction some years after Shaun made her. To me, she never looked right: whoever drew this was not a Renaissance genius. It is clear, too, that someone aside from Shaun has tinkered with her in the past in an effort to give her a credible provenance. But with sums of £100m being bandied about for a real Leonardo, the news that La Bella Principessa might be Sally from the Co-op is certainly startling.

The memoir is full of such claims and revelations. Poor old William Jefferson Clinton bought a bust of Thomas Jefferson in auction that was also by Shaun. Let us hope he does not send over the CIA to rub out its maker when he finds out who really made it. As Shaun puts it in the book: sorry, Bill. The royal family is also owed an apology for the medieval crucifix it acquired on the understanding that it came from the tomb of King John. It did not. It came from the garage in Bolton.

While Shaun generally comes across as a lovable rogue, the book is also packed with genuine bad guys. Very bad guys. Shaun is hardly an angel — he knows it, we know it — but you cannot turn yourself from a comprehensive kid in Bolton into a master forger whose work is scattered around some of the world’s greatest museums without serious collusion from the crooks and mountebanks who inhabit the art world. I thought I knew that world well, having spent so many decades sampling its wares. But I knew nothing. After you read this book you will never — never — trust the art world again.

There is also lots of tiptoeing through the complex moral territory of forgery. The point Shaun keeps making — and it is a good point — is that you should buy things because you like them, not because of the signature in the corner. That way you cannot be disappointed.

The vast majority of the creations that get described in A Forger’s Tale in forensic detail were not sold under false signatures. They were sold as unknown quantities. It was the dealers and the mountebanks, pumped up with imagined self-knowledge, who added the signatures, the fake provenances, the fanciful stories of origin. Shaun was taking them for a ride, but crucially they thought it was the other way round.

From the outside, the art world looks like a world of beauty, inspiration, civilisation and culture. It is not. It is a cesspit. And by making that crystal clear, this book is doing us all a big service.