Truly great artists have a wide emotional range. It’s one of their defining characteristics. Among the lesser talents it matters not if they do only tragedy or only comedy; or only landscapes and only flowers. But among the Picassos, the Michelangelos, the Rembrandts, it matters a lot. To gather the admirers they have — over the ages, across the nations — they need to impress on many fronts.

Goya is habitually included among the ranks of the truly greats for exactly these reasons. He painted the black horror of war and the sunny pleasures of the village. He did tapestry designs and witch etchings. There are churches filled with his frescos and books of advice filled with his terror. He did nudes, he did contemporary events, he did satire, he did social realism. And because he was driven by a powerful fascination with humanity, he did portraits, too. These are now the subject of a superb investigation by the National Gallery.

Goya: The Portraits is the first such show in Britain. To have brought together the armada of faces assembled here — to have forced this many important Goyas out of the clutches of their Spanish owners — is a substantial diplomatic achievement, as well as an impressive display of curation. The Prado could have been a mite more generous and allowed us a few more belly laughs at the expense of the Spanish royals as painted by Goya, but in big-picture terms, this event has everything it needs to tell its story.

Goya’s flight path in portraiture was typically chaotic. He was already 37 when the Count of Floridablanca commissioned the first proper portrait from him in 1783. Before that, he had designed tapestries by the yard for the royal tapestry works in Madrid and filled the churches of Zaragoza with his hard-to-like religious dash-offs. So, like a non-league footballer who signs for Real Madrid in his thirties, he was both set in his ways and suddenly given an opportunity. The result was portraiture unlike anyone else’s: fresh, excited, original and gauche in places.

Floridablanca was one of the most powerful men in Spain, the first minister of state and in charge of infrastructure. Goya shows him in his office, surrounded by lackeys, as he goes about the onerous business of redesigning the country’s canal network. Among the lackeys is Goya, who is showing the first minister a painting. Floridablanca ignores him. Dressed in a suit of outrageously bright poppy red, the lizard-thin duke takes off his glasses and stares out at us magnificently, a great man interrupted in his pomp while running the state.

None of this quite works. All round the picture, realism and symbolism are having a catfight. The composition is confused. Floridablanca is so impossibly tall, he might have been stretched out on the Inquisition’s rack. The expression on his face conveys… er… now there you have me. But in the middle of the muddle, the outrageous red of his clothes emits a trumpet blast of colour that halts you wherever you stroll. Who cares what Floridablanca looks like? Feel that red.

The air of wonkiness that distinguishes these opening pictures takes several rooms to die down and never disappears entirely. The figures are puppetlike. The physiognomies verge on caricature. The children are angelic, and little else. In another early group portrait, The Family of the Infante Don Luis de Borbon, the highly placed royal who ought to be the focus of the occasion, Don Luis himself, is the least prominent personage in the scene. His wife dominates the centre. Goya, again, dominates the left flank. On the right, courtiers form a lively row, one grinning, one thinking. Poor Don Luis, meanwhile, crouches at their feet like an idiot uncle in a wheelchair. As a picture, it only just holds together. As a display of wayward pictorial invention, it’s a feast of possibilities.

And so it continues. From the start with Goya, you feel you are in the presence of an artist who is always working to his own agenda, but who occasionally permits the sitters gathered here to make cameo appearances in his plans. None of the specific concerns of portraiture — likeness, anatomy, character, the imprint of the soul — seem to be Goya’s main concerns.

It’s an aside, but a crucial one, that he is always a superb painter of clothes. Don’t ask me what the Count of Cabarrus really looked liked in 1788, because Goya has given him little more than a standardised rococo mask for a face. But his outfit, vivid yellow-green coat and breeches, is unmistakable, and recorded with a zest you can sense from two rooms away.

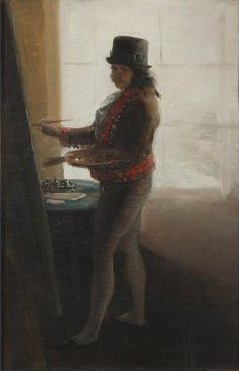

By the time Goya paints the dark self-portrait in which he stands silhouetted in front of a large studio window, making the light conditions as tricky as possible, the meanest test of contre-jour, he is almost 50. But from now on the portraiture flows with no hiccups. The hesitations over, it’s an opportunity to enjoy more clearly the eccentric cast list assembled for us by the National Gallery.

Prominent among them are, of course, the Spanish royals. What possessed them to entrust their historical likenesses to Goya is one of the enduring mysteries of Spanish culture. He became court painter in 1789 and proceeded to immortalise them in the least flattering sequence in the canon of royal portraiture.

We know from history that Ferdinand VII was a particularly bad Spanish king. But by the time Goya had finished portraying him in his best court dress, he appears to have been demoted to the rank of royal bumpkin. Not even Fred West had sideburns as sinister and clumpy. His parents, the notably nicer Charles IV and his busy wife, Maria Luisa, who bore him 14 children and lost 10 more in miscarriages, are gently mocked in the grand portraits of them in the Prado — but not in the two fine full-lengths here. I’ve encountered them before at the Palacio Real, in Madrid, where the glare of the chandeliers made it impossible to see them properly. Here, they are perfectly presented and turn out to be delightful and sympathetic. The show is full of spectacular loans of that order.

Just as notable is the full-length Duchess of Alba, who has arrived from the headquarters of the Hispanic Society of America, in New York. Goya’s notorious and confusing relationship with the duchess is and was the subject of much juicy gossip. The portrait reveals her to have been a surprisingly plain-looking woman with a scintillating sartorial presence. Dressed in black lace that has been painted with amazing invention, she points down at the ground to where Goya has signed his name in the sand, like a dutiful lapdog who knows his place.

As the show shimmers into solidity, Goya takes his time becoming a convincing painter of women. But once he gets there, there’s no stopping him. Thérèse Louise de Sureda (1804) sits in a golden chair dressed in cangiante silks that switch miraculously from blue to pink. Antonia Zarate, borrowed from the National Gallery of Ireland, is nothing less than one of the most strikingly beautiful women in art. The yellow settee on which she perches, and the way the black lace of her mantilla has been captured, are moments of instinctive paintwork that slap you across the face with their impertinent brilliance. It’s immediately obvious, too, how much Manet took from Goya, and how it was all passed on to the impressionists, when invention turned into full-blown revolution.

At the far end of the show, in a spooky portrayal of himself awaiting death in the arms of his doctor, Goya’s art seems to dispense with the niceties and to employ the fewest number of brushstrokes it needs to paint the brutal truth. It’s a remarkable picture. And a remarkable conclusion to a remarkable journey.

I’ve missed out many good things; there are too many to list. Truly great artists never form a solid outline, so no collection of their work can claim to be definitive. This, though, is one hell of a stab.

Goya: The Portraits, National Gallery, London WC2, until Jan 10