Given how much attention our galleries have lavished already on pop art — principally on Andy Warhol, who has now overtaken Picasso as art’s most exposed presence: another week, another Warhol show — it is with some surprise that I am able to comfort you on the subject of Tate Modern’s new exhibition, The World Goes Pop. Yes, it is a show about pop art. No, we haven’t seen it all before. Not at all.

The pop art we know, the one we have been bombarded with, has focused on the two principal streams emanating from Britain and America. There has been some amusing cultural argy-bargy about who got there first, with the British supporters yelping at the American supporters — but, essentially, pop art has been presented to us as a cheeky display of capitalistic delight created by the two loudest capitalist nations of the postwar world.

From our side, it was mainly about desire. Coke bottles, Cadillacs, Elvis, Marilyn, fridges, pin-ups, Mickey Mouse: they had them, we wanted them. But the first thing to say about The World Goes Pop is that it is almost never about desire. Usually, it’s about accusation.

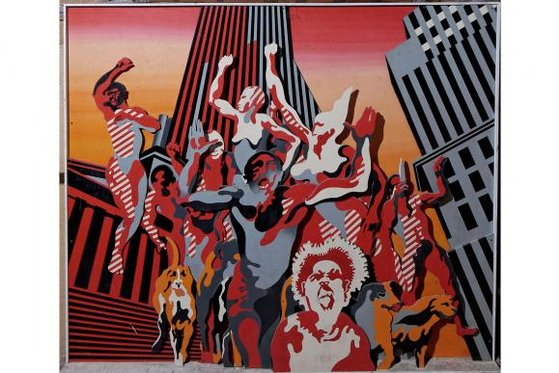

Featuring a global selection of artists who are not, generally, Brits or Yanks, many of whom have been yanked out of the obscurity they certainly do not deserve, this punchy survey skips back to the 1960s and 1970s in Buenos Aires and Madrid, Tokyo and Warsaw, Bratislava and Rome. With 64 artists and 160 artworks, the display comes at us like a French water cannon fired at rioting students in Paris in 1968. And from the off, it seems determined to remind us how ghastly the world actually was in the 1960s, the moment you stepped off Carnaby Street.

The Polish artist Jerzy Zielinski opens the fusillade with a giant head, out of which lolls a giant tongue that has been nailed to the ground. It’s called Without Rebellion, and its task is to summarise the freedom-of- speech possibilities available in a Cold War country in 1970. While Poland was in the hands of the communists, Spain had a fascist dictator at the helm. So the Barcelona artist Eulalia Grau gives us an American muscle car, in the back of which a screaming victim is being “disappeared”, pop art-style.

These really were terrible times for the world. Spain had Franco. Brazil had a junta. So did Argentina. And Greece. France had de Gaulle. Romania had the communists. So did Croatia, and Czechoslovakia. America had Nixon. And by a pleasing art-historical irony, the style best suited to attacking all these international enemies on all these international fronts was pop art.

Why this was so, the busy artworks make quickly obvious. Pop art was just too clever for the censors. Packed as it was with dizzy assortments of cultural references that had been cut out, pasted and madly jumbled, it implied everything, but stated nothing. To know what point Equipo Cronica were seeking to make when they painted a speech balloon emerging from El Greco, filled with pictures of Dick Tracy, the Winged Victory of Samothrace, some invading Red Army guards and the words MAAHW! and VOOMP!, the government department charged with enforcing Franco’s views in Spain would have needed a roomful of encyclopaedias and yearbooks.

Also deceptive was the humour. Say something with a smile and the world thinks you are joking. It’s a strategy satirists have always employed, and is used here to plant various international stilettos into various international backs. Erro’s American Interiors of the 1960s are as effective as they are because they make something smile-worthy out of the invasion of a typical American home by gangs of rabid foreign guerrillas, dressed for the jungle. Nearby, Martha Rosler takes a pop at the male-oriented hierarchy of pop art by showing a woman in an art gallery — doing the vacuum-cleaning! It’s a tip of the hat to Richard Hamilton’s pioneering pop collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing?, and it works because it is funny.

The sheer brightness of pop is another effective disguise. Walking through this lurid show is like walking through a giant selection of liquorice allsorts. Lady Penelope pinks. Tweetie Pie yellows. Green Lantern greens. No wonder the eyewear of choice for so many 1960s dictators was a pair of dark glasses.

While the first half examines the political attacks mounted on the bad guys by grinning popsters around the world, the second half focuses on pop art’s involvement in the politics of the personal. The curators, Jessica Morgan, from New York, and the Tate’s Flavia Frigeri, are transparently determined to foreground the struggle for women’s rights raging through the era, and as soon as Franco and Nixon are out of the way, their show turns its attention to the forgotten women artists of the era. On this evidence, they certainly deserved more attention than they received.

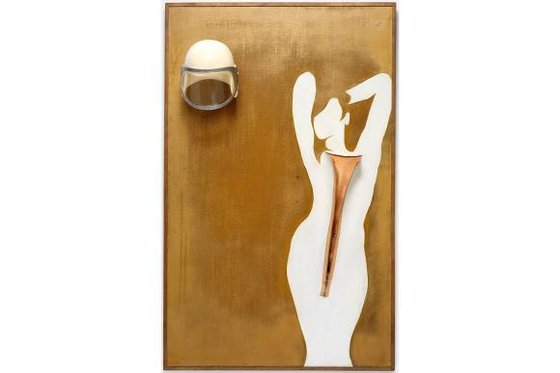

Evelyne Axell, a Belgian popist who died in 1972, and whose feminism was charged slyly with eroticism, is a fabulous rediscovery. Her wall relief, Valentine, features a space helmet like the one worn by Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman cosmonaut, alongside a flying costume unzipped to reveal that, underneath, Valentina was all woman. It’s intended, I imagine, as a comment on the objectification of the female. But the fact that naughty doubts about its purpose are allowed to linger is what makes it such a successful artwork.

Jana Zelibska, from Slovakia, is another sly feminist, using the seductive pop language of the bathroom interior to produce a set of disorientating female close-ups that can only be glimpsed through curtains or in mirrors. By making peeping toms of us all, Zelibska is both an accuser and a supplier. It’s a tribute to the unsettling freshness of her work that you leave the exhibition uncertain of her motives.

There are scores of others. The single best thing about this show is the fascinating array of new artists it brings together for us from around the world. Pop art washed up on many troubled shores. And something about its immediacy and its bounciness made it particularly popular with inventive naysayers.

The show also begs an important question: how many more of art’s great movements have a lot more to tell us once we bang open the atlas?

The World Goes Pop, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Jan 2