The Jackson Pollock exhibition in Liverpool begins as all exhibitions should begin — with a burst of art that thumps you in the chest and forces your mouth open. At least, that’s what it did to me. Staggering unsteadily between the first half a dozen pictures, I felt things I cannot describe adequately to you here because they were art things, not word things. Throbs. Expansions. Eruptions. If the rest of the show maintained the levels of excitement achieved at its opening, you might not be reading this now, because I’m not sure I would have survived it. But it doesn’t.

Pollock exhibitions are rare in Britain. So rare, I do not recall seeing any since the 1999 retrospective. If you want to encounter the greatest and most emblematic of the abstract expressionists, you need to tour America, where his work is scattered democratically about the national museums, and where no single collection owns enough to tell his full story.

In Britain, there are no great Pollocks to be seen anywhere. The Tate’s own picture, Summertime, from 1948, included in the present selection, has spectacular dimensions — it’s 19ft wide — but is a weak work in which the excitements are rolled out in a thin strip, as if someone has squeezed them through a pasta machine. The density of Pollock’s drip pictures usually makes his sources difficult to discern. With Summertime, it’s too obvious too quickly that he has been looking too fondly at Miro.

The Liverpool show has called itself Blind Spots. Its ambitions are brave and Tate-ish. The bravery comes in daring to mount a Pollock show at all, when doing so is so difficult. His paintings are fragile. Their conservation is problematic. If you have one, the last thing you want to do is lend it. Getting five roomfuls of assorted Pollocks into Britain must have been quite a task.

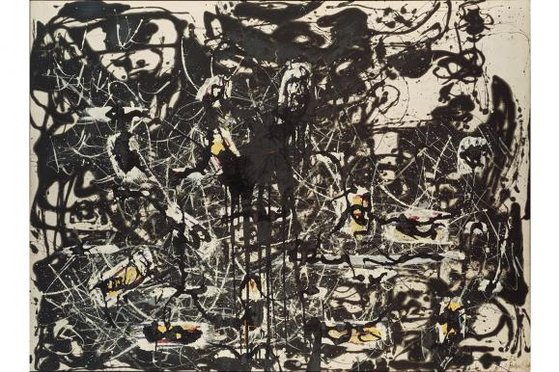

Where it becomes Tate-ish is in the choice of subject matter. The present event’s focus is the black-and-white art Pollock produced early in the 1950s, when he was seeking to become a deeper, darker, more austere artist. It’s his least popular and most difficult moment: the one everybody tries to avoid.

I should quickly add that this is not what is examined at the start of the journey — the part that sent me reeling. Happily, Blind Spots commences with a short reminder of what Pollock had previously achieved — a handful of the full-colour paintings from 1948 to 1950, which saw him weaving dense and delirious patterns with drips, dribbles and splatters that look as if they have been taught how to move by a galaxy. Everything is swirling, orbiting, intersecting. It’s a bit like gazing up at a meteor shower, but also like gazing down into a molecule.

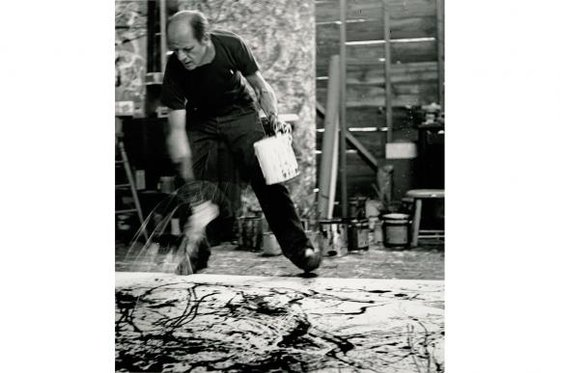

The painting that got me going was called Number 3, 1949: Tiger. It features a dense orbit of reds, silvers, blacks, yellows and greens, at the centre of which a dagger of white seeks to pin everything in place, like a stick trying to stop a river. The materials used to create this throbbing masterpiece of action painting are listed as “oil paint, enamel paint, string and cigarette fragments on canvas”. As with all Pollock’s pictures, you can feel him making it while you’re looking at it — stooping, pirouetting, twitching, dripping to the left, dripping to the right, dancing the fabulous art dance he’d invented, all the while dropping careless ash into the paint from the fag on his lip.

Number 3, 1949: Tiger is worth the admission charge on its own. Yet so eloquently does it summarise Pollock’s approach, everything that follows is doomed to appear a lesser achievement. Compared with Pollock in full colour, the black-and-white work of 1951 will always look austere, problematic and, frankly, dull.

Why did he turn to black? The show never specifically tells us. My guess would be that, as an agoniser by nature, he had become disillusioned with his notoriety as Jack the dripper and was trying to turn himself into a more obviously serious artist. The elephant in the room is surely Picasso’s Guernica, which was touring America at exactly this time, and which had shown observers how to achieve a monumental seriousness with black-and-white art.

Unfortunately, Pollock was no Picasso. Having dispensed with figurative references in his action painting, his efforts to reintroduce them in his black-and-white art are initially unconvincing. For a couple of rooms, we see him doodling with dribbles of black. His wife, Lee Krasner, described him using a large syringe, “like a giant fountain pen”, to dispense the paint. The results are a cross between painting, drawing and calligraphy, with a lot of the white canvas showing through. Occasionally, the swirls and blotches suggest a faraway figure or a face. More often they remain as squiggles and blotches in a display of austere mark-making that’s hard to love.

That Pollock himself found this phase in his art unsatisfactory is made clear by what happens next. Having kept colour out of his paintings for a year, he allows it to return in small but effective increments. At the same time, the figurative elements grow more obvious, too. By the time we get to Number 7, 1952, the image formed by the swirling drips of black, enlivened with small splashes of yellow, is clearly a large and monumental head.

In pictorial terms, his problems are over. Having found a convincing way to thread his art between abstraction and figuration, and having learnt again how to use colour in targeted patches, Pollock was through his dodgy period. On this evidence, he was set to achieve marvellous things again. And to finish itself off properly, the present show ought to have climaxed with The Deep, that particularly spooky painting from 1953 of a black chasm in a white expanse, which forms such a natural conclusion to Pollock’s troubled experiments with black and white. But The Deep belongs to the Pompidou Centre, in Paris, and is hardly ever loaned.

Instead, the wrapping-up duties fall to Portrait and a Dream, also from 1953, a hybrid of abstract and figurative elements that is as delicately mysterious a painting as Pollock ever produced. On the left, the black squiggles form a blur in which I thought I could discern a pair of lovers locked in an ecstatic embrace. I might have been imagining it. That’s the dream. On the right, a monumental head has been part painted, part sculpted out of thick layers of grey and orange. That’s the portrait. It’s surely a self-portrait.

As I said, in pictorial terms Pollock’s problems were over. In personal terms, alas, they were increasing. By the time we leave him, he is already a shuddering alcoholic who has all but ceased to work. By 1956, he was dead, having driven his Oldsmobile into a tree. All these struggles led nowhere.

Jackson Pollock: Blind Spots, Tate Liverpool, until Oct 18