It has been several generations since Greek art felt relevant. Of course, college professors and television historians have never stopped placing it at the summit of ancient achievement — that’s their job, to give us a neat civilisational framework we can envisage — but that is merely professional culture-mongering. Where it counts, on the front line of art, in our daily aesthetics, it has been many, many years since the efforts of the sculptors Phidias or Polykleitos have meant much to us. By my reckoning, you have to go back to the generation of Henry Moore to find the Greeks having a tangible impact on British art.

Why this has happened is a no-brainer. The Greeks don’t speak to us any more. Where the gleaming whiteness of Greek art and architecture used to feel like a civilisational template, it now feels like a restriction. Given a choice between Heracles and a hobbit, we go for the hobbit. The world has turned multicultural, colourful, misshapen and spicy, all the things, we reckon, the Greeks were not.

It is in these circumstances, and with this opposition, that the British Museum, in a moment of curatorial brilliance, has chosen to confront us once again with Greek achievements. More than that, the display sees Greek art very differently from the way it was seen in the past. Instead of the haughty cultural whiteness of old, what we get here is art that is, yes, multicultural, colourful, misshapen and spicy. Hah!

The key to this new understanding is found in the second room, where a group of gaudy re-creations of ancient Greek statuary, borrowed from the Glyptothek, in Munich, make the point, very loudly, that Greek art was actually highly coloured and never purely white. It may have come out of the ground, centuries later, with all the paint worn off, but that was not how it went in. Reader, we’ve been worshipping the wrong aesthetics.

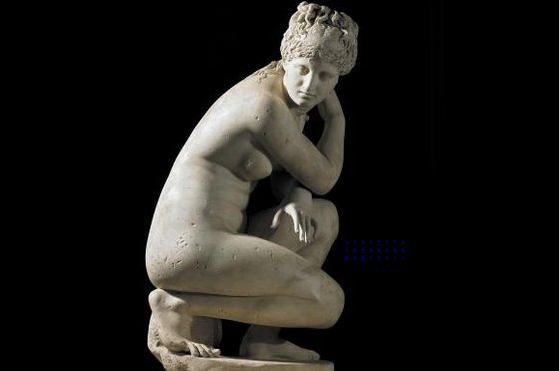

Back at the beginning of the show, this ambition to serve up some new Greeks is made fully evident by the first thing you see: the looming backside of a crouching Aphrodite, pitted with tiny holes, as if someone has fired a shotgun at her arse. This is actually the same lovely Aphrodite, goddess of love, who usually greets us in the Parthenon rooms at the BM. There we see her from the front, as she covers her nudity with sweet, emblematic modesty. Here, approached from the back, the way she’s supposed to be approached, she becomes a provider of voyeuristic thrills as we tiptoe up behind her and sneak a look.

Although it’s called Defining Beauty, the show isn’t really about that. It’s about the many ways in which the human body was represented in Greek art. The bulging terracotta woman with the squashed muffin rolls squeezed comically into an armchair near the end is not a thing of beauty. Nor is poor old Socrates, whose huge philosophical contribution tends to be forgotten in the portrayals of him as a podgy human satyr, preying on young boys in the gym.

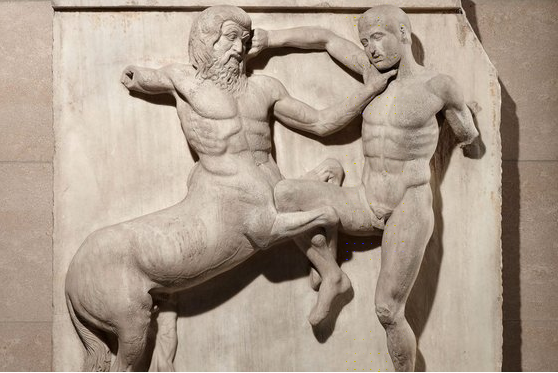

What is true is that the Greeks were the first ancients to recurrently and proudly get their kit off in their art. The Egyptians would have considered it unseemly. The Cypriots didn’t do it. Nor did the Persians. And this pioneering Greek nudity, says the show, as it impresses us with a superb athletic cast of striding spear carriers and reclining middleweights — some of whom are making their first appearance away from the other Elgin Marbles — was a concept, not a description.

Beyond Aphrodite’s tempting rear, a mighty opening threesome of heroic male athletes, wearing not a stitch as they flex and flaunt their perfect bodies, makes the same point. At their centre is Myron’s famous Discobolus, the discus thrower, whose pose, unpicked cleverly in an adjacent caption, consists entirely of opposites: one hand hanging, one hand raised; weight on one leg, not on the other; one foot down, one foot up. This is nudity that places mankind at the centre of nature’s great geometry and deliberately parallels the harmony of the universe.

It’s tempting, however, to see something of our own times in this constant disrobing. The sculptural airbrushing that rids the Greeks of their unsightly bits may differ in purpose from our own airbrushing, but it achieves the same results. The shaved, glistening and mightily six-packed specimens gathered here could all be played by Hugh Jackman. One notable difference is the size of the willies. We like them unnaturally big because we’re obsessed with sex. The Greeks liked them unnaturally small because sex was the last thing on their minds.

Not that they couldn’t do sex when they wanted to. In its determination to rebrand them, the show includes some notably uncivilised depictions of sexual abandon. Have you ever seen a satyr and a deer enjoying the 69 position? The startling gym scenes painted onto the sides of wine coolers, meanwhile, in which aroused older men balance handsome young boys on the ends of their Doric columns, are involved in a second conceptual war — “the war against reason”.

All this is beautifully presented and flamboyantly argued in a display with a magical second presence in the reflections and repetitions of its glass cases. Dispensing with a legible chronology and bouncing instead from treat to treat, it humanises Greek humanism with surprises.

There is, thus, a section on babies, who, for the first time in art, begin popping up on the sides of pots and vases as little bundles of fun who like to scamper. I was particularly taken by the miniature wine jugs from which Greek toddlers were encouraged to take their first sips at the age of three, in a Dionysian ceremony that celebrated their survival of infancy. Kawaii Greek art? Who saw that coming?

There are also unexpected appearances on wine jugs and terracotta statuettes of beautifully modelled African faces from the far reaches of the Greek empire; while the rare terracottas that have survived with their original colour intact, especially a delightful scene of two young girls playing knucklebones, are so disconcertingly realistic.

It’s as if everything we have previously imagined about the Greeks is being challenged and updated. Off the top of my head, I’m not sure if I can remember a more obviously revisionist show.

Defining Beauty, British Museum, London WC1, until July 5. Read Christopher Hart’s review of Introducing the Ancient Greeks by Edith Hall in Books