The two things most people in the art world know about Marlene Dumas are: she is a South African who grew up in the apartheid era; and she is the most expensive living woman artist. Actually, the second is no longer true. In 2011, Cady Noland’s Oozewald sold for $6.6m, making it marginally more expensive than the $6.3m paid in 2008 for Dumas’s painting of five prostitutes waiting for a client, called The Visitor. However, once you have been “the most expensive”, nobody can ever take away the badge.

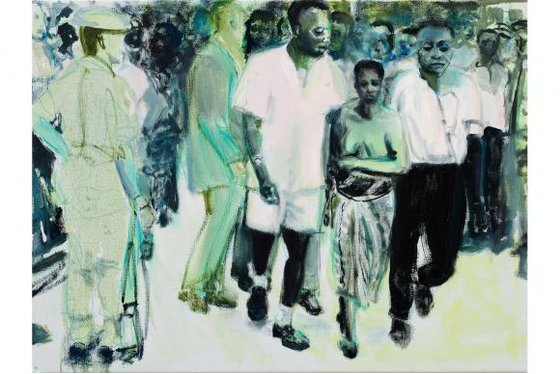

I mention all this money here as a warning, because at the heart of Dumas’s presence there is a disconnect: a sense of mismatch. Her art, rooted in the soil of her South African past, is about blackness versus whiteness, about apartheid, about the image of women, about identity, about war, about the voice of the individual in the crowd. It could hardly be more right-on. Yet the global super-rich have been falling over themselves to acquire it. It’s all very surprising.

Tate Modern’s encapsulation of her career has duly called itself The Image as Burden, a glum title for a celebration of painting, but one that signals the problematics ahead. If I had titled the show, I would have called it The Burden of Modernity. Or, perhaps, How to Be Old-Fashioned in a Contemporary Way. What we actually witness here, at the start of her journey, is a clumsy attempt by deep and ancient human emotions to express themselves with fiddly and ill-fitting conceptual methods. It’s like watching an elephant trying to squeeze itself into a bikini.

As a student in Cape Town in the 1970s, Dumas began cutting out photos from newspapers, redrawing them in 3H pencil and captioning them with scribbly texts. She was trying to be progressive and western. But the mushy stuff below — the pathos, the empathy, the disquiet — kept soaking through. It’s difficult to imagine a clearer example of the heart saying one thing and the brain saying another than her first, spidery collages.

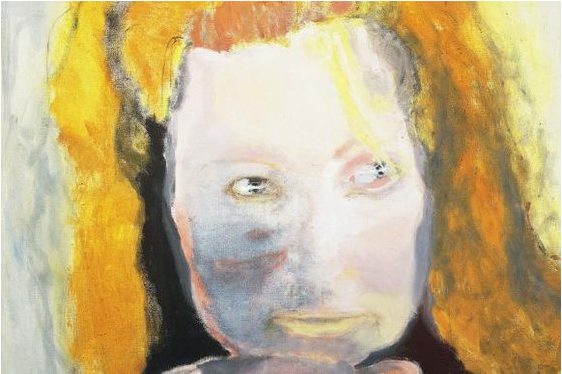

Thankfully, this conceptual phase didn’t last long, and after three walls of timid 3H fiddling, we get quickly to a gallery filled with the large painted heads for which she is best known, and which announced her arrival in the international world so loudly in the mid-1980s. They remain magnificent and powerful.

Based on humble and often nondescript photos, the heads have a small ambition to achieve a likeness and a much bigger one to say something universal about the human condition. Martha — Sigmund’s Wife, painted in 1984, is a portrait of Freud’s wife, the rarely noticed Martha Bernays. Half of her face is red. The other half is grey. Her eyes and her hairline are legible, but her mouth has been rubbed out with smudges of white. She is simultaneously a human presence and a human absence. Which is what happens to you if you’re Freud’s wife.

All the heads have an in-built sense of symbolism. All of them seem to have been through a battle to find the best painterly approach with which to suggest their bigger meanings. A portrait of Dumas’s mother, also called Martha, is as washed out as the Turin Shroud. While a portrait of Moshekwa, an artist friend of Dumas’s, and a rare appearance here by a male face, uses a surprising splodge of Rothko purple across the forehead to smuggle powerful abstract expressionist emotions into the image.

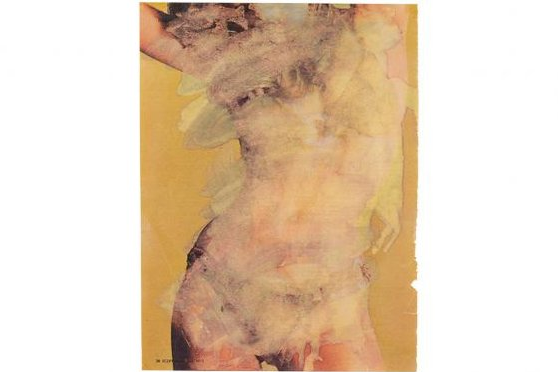

As a display of inventive mark-making, all this is impressive. The suggestive possibilities of paint are treated to an exciting exploration. Here, it’s done with splodges. There, with monochromes. Unfortunately, painting large heads is not enough for Dumas and, having shown how potently she can do it, she spends the rest of the show growing more ambitious in her subject matter, less impressive in her art. A room filled with full-length female nudes has as its centrepiece a two-part portrait, or diptych, featuring Princess Diana and Naomi Campbell, called Great Britain 1995-1997. Diana is in a pink princess ballgown. Naomi is in the nude. Painted separately, then brought together as an afterthought, the two contrasting likenesses — black and white, clothed and naked — are seeking to comment on the binary female reality of modern Britain. But the choice of subjects is as symbolically clunky as a shot of Big Ben in a Hollywood title sequence.

Dumas is at her best when she achieves her power with inventive paintwork; at her worst when her meanings are conveyed with stiffly obvious imagery. Having grown up in South Africa under apartheid, she is particularly sensitive to separations and colour codings. But the painting of a line of Orthodox Jews praying before that hideous new Berlin wall with which the Israelis have separated themselves from the Palestinians is little more than a black-and-white cartoon. Mindblocks, meanwhile, from 2009, a row of large grey slabs stacked across the picture, is based on a grim close-up of an Israeli roadblock.

This pictorial literalness culminates in a particularly off-putting Crucifixion. Ouch. What kind of contemporary vanity could have driven Dumas to repeat an image freighted with as much past as the Crucifixion? Inevitably, her feeble effort finds itself shown up massively and comprehensively by all those better Crucifixions that came before her.

Speaking of the past, the Fitzwilliam Museum, in Cambridge, announced last week that the two Renaissance bronzes of male nudes riding a panther now on show there are actually by Michelangelo. I remember them from their last gallery appearance, at the Bronze exhibition at the Royal Academy. They are very elegant. Very beautiful. And very certainly not by Michelangelo.

Not only are the faces wrong, but so, too, is the heft and mood of the two anatomies. Michelangelo didn’t do decorative pairs. In every surviving artwork by him, there is a sense of him going mano a mano with his subject. You can’t go mano a mano with two elegantly matching nudes, riding a panther.

Marlene Dumas, Tate Modern, London SE1, until May 10