I have always had issues with Egon Schiele. Not just because of the alleged incest with his sister, or the child models he stripped and sexualised in his work, or the appalling treatment he dished out to the young women unfortunate enough to get entangled with him. Most of the worst Schiele stories are unprovable. The Jimmy Savile side of his nature that led to his arrest for seducing an underage girl in Neulengbach in 1912 was perhaps exaggerated by the accusing citizens whose village life he had gatecrashed.

What can be proved without trusting to rumour is the character of his output. Schiele is one of those artists whose art is so mannered that mistaking it for anyone else’s is impossible. Like Modigliani, like Chagall, like — at the extreme end of things — LS Lowry, his style appears to be doing most of the work.

The other problem is his emotional range. There isn’t any. All Schiele’s art is set in the same narrow band of psychosexual angstiness. He doesn’t do happy, he doesn’t do gentle, he doesn’t do warm, he doesn’t do intelligent or poetic. Schiele only does charged and harsh. There’s a cruelty to his depiction, an emotional severity, that makes Biafrans of all his sitters, especially his women. In the aesthetic concentration camp of Egon Schiele’s art, everyone is always shivering, wired and neurotic.

And because he died so young, aged just 28, in 1918, in Vienna, all these problematics are frozen in their final state. Schiele in his immature, shouty, rock-star form is all we will ever have. The modern world, which worships rock-star forms, doesn’t mind any of that; indeed, it loves it. But the passion for Schiele that has sent his prices soaring to ridiculous heights at auction is, in itself, an immature passion. Like the passion for art nouveau, or for Salvador Dali, it is something you grow out of.

These were the prejudices with which I entered Egon Schiele: The Radical Nude at the Courtauld Gallery. They were not, however, the prejudices with which I exited this marvellous and punchy little show devoted to the drawings Schiele made of the human nude between 1910 and 1918. From the moment you walk in, the art on the walls buffets you with its emotional force. While it certainly didn’t cure me of all my disbelief, it just as certainly slapped some sense into me on the subject of Schiele. Yes, he was a narcissistic weirdo you wouldn’t want coming anywhere near your sister. Yes, his mannerisms do most of the work. But what exciting mannerisms they can be.

The son of a railway worker, Schiele (1890-1918) arrived in Vienna in 1906 with his foot pressed to the floor on the rebellion pedal. Within a year, he’d left his first art school. Three years later, he left his last one. He was 19. We come to him here just a year later, in 1910.

A triptych of emaciated male nudes, contorted into strange angles, was apparently modelled by Schiele himself. How he managed to twist himself into these impossible positions in front of a mirror, while keeping his hand free to record it, is again a matter of conjecture. Imagine a nude twisted out of wire coat hangers. Most naked bodies have two elbows. Schiele’s naked bodies have elbows at every joint.

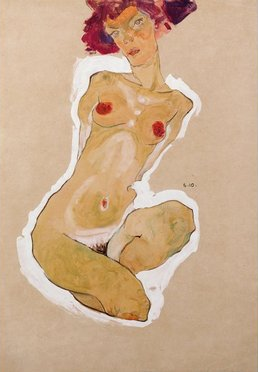

None of these first figures is conventionally complete. Aggressive croppings often cut off their heads or feet. This way and that they twist as they search for the boniest aspect to present to you. And, from the start, the constant exposing of genitals that is called for here has an unglamorous and harshly voyeuristic aspect to it. Sorry, but if you were a parent in Neulengbach, and Egon Schiele drew your prepubescent daughter naked, the way he drew the so-called Sick Girl in 1910, with an eerie halo around her exposed sex, and her hands pushed fretfully into her mouth, you would have had him arrested too. This art is many things, but one thing it certainly is not is innocent.

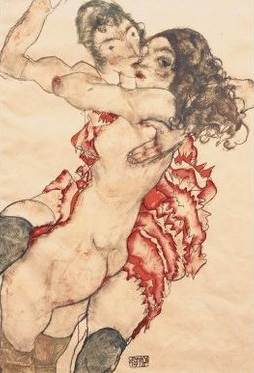

Nor is it as strikingly original as is claimed. How could it be? He was only 19. The very fact that we are looking at works on paper, painted and drawn, alerts us to the powerful example of Toulouse-Lautrec, whose best work was done exactly this way. See the thin and glum figure of Jane Avril leaving the Moulin Rouge, scrawled dryly onto millboard downstairs in this same Courtauld Gallery. The dramatic croppings are also Lautrec-like, as, of course, is the consuming interest in lowlife sex in women showing off their bits and in confusingly entwined lesbians. Lautrec did all of that first.

The presence of Rodin is tangible, too, in the twisted sections of acrobatic body that stand in here for the complete human. As for all the red pudenda glowing like traffic lights beneath all those lifted nightdresses — did you see what the octopuses got up to in the Shunga exhibition at the British Museum last year? When it comes to glowing red pudenda, Schiele is a follower, not a pioneer.

However, what none of the above have, and what distinguishes everything on show in this ultimately marvellous display, is the psychological fierceness of Schiele’s art: the way his sitters seem to be arrowing their thoughts at you, when it ought, surely, to be the other way round. Initially, this fierceness also appears borrowed. In the drawing known as Sneering Woman, the angry grimace on the face of his topless sister, Gerti, is clearly derived from the notorious girning character heads created in the 1770s by the mad Viennese sculptor Franz Xaver Messerschmidt. But where Messerschmidt was content to distort only his heads into unwordly grimaces, Schiele expands the approach to the entire human body.

By the show’s second room, his radical nudity has lost some of its ambition to distort and grown a touch more solid. The naked females are still painfully thin and straggly — should you ever have need to name the opposite of a Rubens nude, here they all are — but their boniness has acquired a more elegant outline. And not even a Shunga octopus could adopt a set of poses as intricate and inventive as these. It’s kinky, it’s sexy, it’s outrageous, and it makes you want to cross your legs. But there isn’t much art, and certainly not many works on paper, that comes after you as tigerishly as this.

At the Royal Academy, a rare show has appeared devoted to the 16th-century Italian master Giovanni Battista Moroni. It’s rare because Moroni (c1520-79) has spent most of his posthumous career out of fashion. He was popular in his own lifetime. He’s been popular in recent decades. But in the 400 years that intervene, he was roundly ignored.

Moroni’s speciality was portraiture. A master of realism, he brought observational skills to Italian 16th-century painting that belong more usually in the art of the northern Renaissance. His sitters have wrinkles you can count, and stubble that will scratch you. They look at you from deep within themselves and involve you in their thoughts with a baroque intensity that is half a century ahead of its times.

Most often, Moroni poses them against plain grey walls that also appear to have something preternaturally modern about them, as if the Muji colour schemes of our own world have been Tardised back to Bergamo in the 1560s. But all this we already realised. The National Gallery has one of the world’s best selections of Moroni portraits. They are well loved and well known. Less expected is the religious art included here.

Moroni the religious artist is a surprise package. His best moments come when he is able to mix the two worlds: the divine at the back with the real at the front. Thus, an idealised Jesus in the distance stoops down to be christened by John the Baptist, while a youthful Bergamese gentleman in the foreground, his lower face covered in perfectly observed bumfluff, seeks unsuccessfully to appear deep in prayer. The front convinces. The back doesn’t. It’s a strangely effective dichotomy.

Schiele, Courtauld Gallery, London W1, until Jan 18; Moroni, Royal Academy, London W1, until Jan 25