SOONER or later, it was bound to happen. At some point, someone was always going to have a go at rehabilitating Allen Jones by giving him a retrospective.

Jones’s “crime” is to be the most obviously sexist artist in Britain and, for my money, among the most sexist ever to appear anywhere. It’s a strange achievement. When you look back at the history of art, particularly in the modern era, you encounter cascades of machismo. Look at Toulouse-Lautrec. Look at Picasso. Look at Egon Schiele. All of them were relentless tuppers of their models; all their art objectifies women. But because it remains great art, we forgive them. Why, therefore, can we not forgive Allen Jones?

Because it’s not great art. Usually, it’s appalling art. And, as this often ghastly event makes very clear, the final problem is the quality of the image-making. You can be a sexist, but remain a graceful artist. You can be a wicked artistic presence, yet remain fascinating. What you cannot be, if you are a sexist, is silly. Silliness destroys every grace and depth.

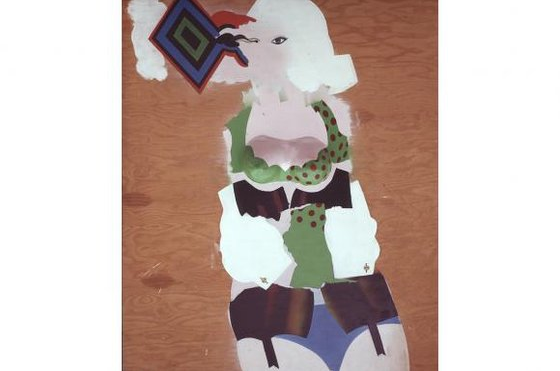

The Royal Academy has taken the plunge because Jones has been an academician since the 1980s. The usual reading of his career — the reading that has put people off mounting a retrospective until now — is to see him as a briefly brilliant pop artist who emerged at the beginning of the 1960s, in the same generation as Hockney, Boshier and Kitaj, but whose work then took a disastrous sexist turn. It inspired him, in 1969, to produce the three most offensive sculptures in postwar British art. All three feature half-naked women in restrictive leather fetish gear, doubling as pieces of furniture. In Table, a topless woman in the doggy position offers you her buttocks as she holds up a glass coffee table. In Hat Stand, she stands there in thigh-length fetish waders, firing her pointy nipples at you and holding out her hands so you can hang your hat on them. In the one I like the least, Chair, she lies on her back and pulls her legs up under her chin so you can sit on her.

The academy has decided to open its retrospective, feistily, with a pair of these table women, who greet you to the event in a room hung with burgundy velvet, like a belle époque brothel. The show ahead dispenses with chronology as it seeks, sneakily, to blur the timescale of Jones’s achievements by turning them into a thematic stew. Thus, a large gallery devoted to his paintings features work from the 1960s to now. The aim, I imagine, is to suggest a continuity in his treatment of colour and subject. It doesn’t work. The early art, the pop art, is always spottable and always superior to the sexist twaddle that surrounds it.

Jones’s pop art, with its floaty patches of gorgeous colour and its poetic urban moods, manages to make London life appear romantic, mysterious, whispery. Interesting Journey is a face in a window gazing out psychedelically, with pluses in one eye and minuses in the other; 2nd Bus, from 1962, is the side of a London bus, floating past you, with the people on the top deck, in miniskirts and needle ties, dancing a silent lovers’ bop. It’s as if Kandinsky has come to town, smoked some pot, boarded a bus and begun noticing the intoxicating abstract beauty and the mysterious urban poetry of swinging London.

During my preview, I bumped into Jones himself, so I asked him if he had actually been smoking pot when he produced these shimmering, unknowable, heightened urban views. He said no. But added, Clintonesquely, that everyone around him was, so maybe it seeped in.

All this is splendid. The city’s sights have been departicularised, its colours heightened and loosened from their origins. The problems begin in 1964, when Jones moved to New York. Heaven knows what he got up to in late-night Manhattan, but it turned his art from poetic and beautiful to seedy and shiny. The sudden domination of his pictures by muscular women in stilettos, the corseting, the tying-up, the sadomasochistic role-playing, feel like glimpses into an X-rated psyche.

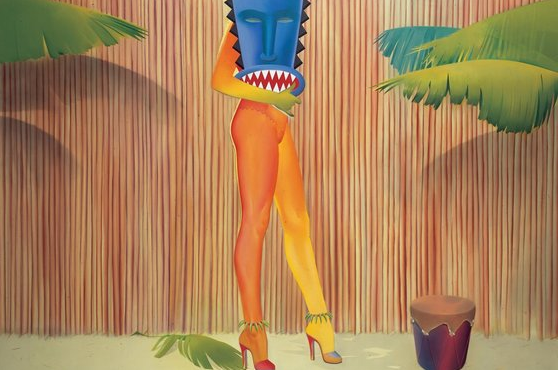

Even worse than the furniture-women are the painted allegories in which the interchangeable Jonesian pin-ups find themselves involved in pictorial shenanigans of irredeemable silliness. Night Moves, from 1985, is some kind of contemporary brothel scene, in which acrobatic couples grope and stroke in the dark while a woman dressed as a mermaid is crucified at their centre. That’s right. A crucified mermaid.

The display makes an effort to persuade us that there’s an important line of continuity connecting the gaudy allegories to the earlier pop art. But there isn’t. Once Jones had discovered the hard, shiny, muscular, leather-clad, stiletto-shod American pin-up, he was never again to paint a convincing female presence. All his women look like Halle Berry as Catwoman. All are preyed on by spooky, creepy, furtive Peeping Toms.

At some point — thinking back to Matisse, perhaps? — he discovered ballroom dancing. A suite of paintings and sculptures coloured the citric yellow of a concentrated orange drink feature a set of swirling tangos seemingly choreographed by Madame Whiplash. They’re strictly terrible.

The show’s final room has the air of a Soho basement about it. Filled with female sculptures, all of whom could find work as a sex doll, it features Jones’s creepiest moments and provides the most vivid proof of how insensitive his art had become. The most awful female figure here is not the life-sized Diana Rigg in a brown catsuit, who’s been turned into a refrigerator; or the totemic lump of wood with a vagina attached. Worse than both of those is a big-busted Kate Moss with Beyoncé buttocks and Tina Turner legs, who struts up a catwalk and shoots us a Debbie Harry profile in a new painting called Kate in Red. Allen, Kate Moss does not look like that.

No grace. No insight. A befuddled sense of colour. Morally bankrupt. And, worst of all, very silly. This is such a bad show.

Allen Jones, Royal Academy, London W1, until Jan 25