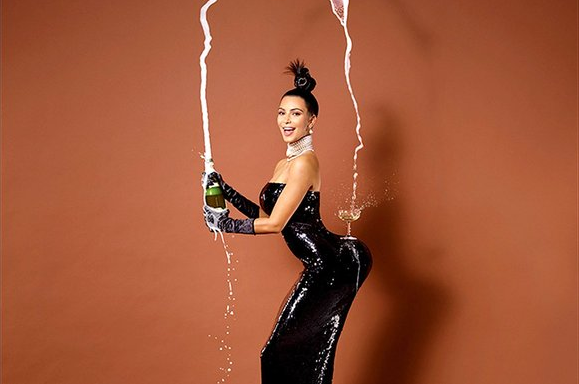

As soon as I saw those pictures of Kim Kardashian balancing a champagne glass on her botty, two unfortunate words sprang to mind: “Hottentot” and “Venus”. They were unfortunate because the case of the Hottentot Venus is a blot on human cultural history and any modern event that causes us to remember it needs to be regretted.

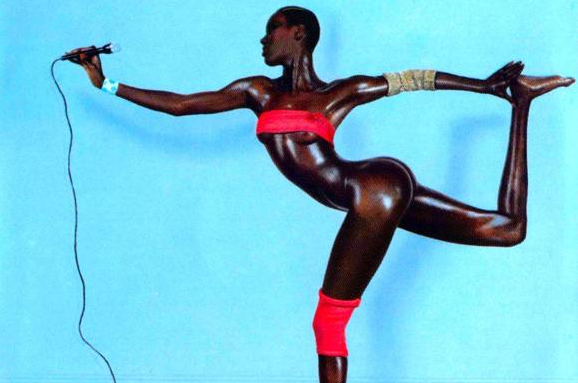

The photographer who took these immediately notorious pictures was Jean-Paul Goude, that bad boy from the Grace Jones era who has lots of previous on the Hottentot Venus front. Goude knew what he was doing when he placed that Babycham-style glass on Kardashian’s protruding rear and directed a provocative arc of bubbly into it. The old balancing- a-glass-on-your-arse trick was one of the most accomplished specialities of La Vénus Hottentote.

Of course, Kardashian, who came to fame in the reality TV show Keeping up with the Kardashians, is already notorious for the size of her derrière. In the absence of any actual accomplishments on her part, her botty has served to loom up monumentally in our cerebral placement of her. Nor is she alone in this. Culturally we appear to have entered an era of buttock worship the like of which the world has not really seen since the closure of the Palaeolithic age. Kardashian on the cover of Paper magazine, pressing her significant backside fully into our consciousnesses, is merely the latest episode in a noisy cultural rethink of the presence and function of the female buttocks.

As far as I can tell, this celebration of impactful bottoms commenced with the incessant waving of her rump in the air by the American actress and singer Jennifer Lopez. When you think of JLO you see expanses of white satin stretched to breaking point across the rounded heights of her Dolomites.

She was followed in the booty wars by that particularly fierce exposer of her posterior, Nicki Minaj, whose personal rear peak was reached with the video for Anaconda that consisted almost exclusively of close-ups of her fundament bouncing around a jungle set, intercut with occasional shots of her singing. On the first day of its release, the Anaconda video was watched by 19.6m viewers.

This then is the cultural territory in which the Kardashian photos have now planted their flag. And I reckon what we are witnessing here is a power struggle that is now being enacted in US culture — a buttock-grab — between the scrawny white Caucasian hindquarters, tucked neatly into some slacks from Saks, and the billowing, bulging buns sported and preferred by more recent arrivals to the American dream.

Lopez, Minaj and Kardashian are all members of ethnic minorities who have settled and succeeded in America. Lopez’s pioneering rear may owe some of its splendid fullness to the exercise she gives it as a dancer, but it owes more to a rich genetic inheritance from her Puerto Rican origins. Your typical Puerto Rican verso has a different cut from your typical Caucasian verso. Just as the white and pinched Caucasian bottom stole America from its rightful native owners, so the mighty non-Caucasian buttocks of JLO and co are seeking to steal it back for the natives.

It’s the same with Minaj, whose Trinidadian roots can be traced even deeper, via the iniquities of the slave trade, to Africa itself. Which is where the Hottentot Venus comes in. Her tragic story commences in 1790 in the Gamtoos Valley of South Africa where she was born Sarah Baartman, a tribeswoman of the Khoisan people. Its women were celebrated for the size of their buttocks or, to give this fullness its technical term, their steatopygia. When Baartman was barely in her twenties she was sold to a Scottish doctor named Alexander Dunlop who brought her back to England and toured her around the country as the Hottentot Venus.

Crowds would gather to gaze in awe at the spectacular size of her buttocks. In the cartoons and newspaper illustrations that survive, Baartman stands there forlornly displaying her naked seat like . . . well, like Kim Kardashian on the cover of Paper magazine. Except Kim is smiling triumphantly while Baartman is not.

When Dunlop died in 1814 Baartman was sold on to a French circus showman who took her to Paris and hired her out for private viewings. She died in 1815, impoverished, malnourished and, according to some accounts, forced into prostitution. Her remains were then submitted to a thorough medical examination before being put on show in a French museum. Later they were transferred to the Musée de l’Homme. Perhaps Goude encountered her there.

The Khoisan people are among the oldest inhabitants of southern Africa. These days they are understood as everybody’s original ancestors — all of us can trace our origins back to them.

Artistically too the Kardashian photos can be casually suspected of speaking an ancient sculptural language. When I look at her on the cover of Paper magazine I see a balloon with an elastic band around its middle — a naked woman so impossibly proportioned that she must surely have been achieved with stretchable plastics and a pump. It’s unarguably true, though, that your bigger woman has a long and crucial artistic past. And I’m not just talking Rubens here.

Back at the beginning of the story of art, many millennia before Rubens began expressing his preferences, the sculptors of the Palaeolithic age had already focused exclusively on the larger woman. In the whole of Palaeolithic art there is not a single representation of what we might call the thin-arsed Caucasian Upper West Side type. All the early Venus statuettes feature fuller females with extended breasts and large buttocks.

Picasso, who was influenced mightily by Palaeolithic Venuses, had replicas of two of them in his cabinet when he was painting Guernica. One was of the famous Venus of Willendorf, that beauty of many bulges who was discovered in Austria in 1908.

The other was the so-called Venus de Lespugue, a fabulous spoon-sized Venus carved out of an ivory tusk, discovered in the Pyrenees in 1922. She’s the one who, at first sight, also looks exactly like Kardashian on the cover of Paper.

More recently Lucian Freud outed himself as a surprising champion of abundant adipose tissue with his portraits of the sleeping benefits supervisor Sue Tilley.

It is tempting, therefore, to view all this rampant buttock flashing by Kardashian, Lopez, Minaj et al as some sort of reclamation of an ancient and natural cultural territory. But you would have to be pretty stupid to see it that way. The big difference between the ancient Venuses in our museums and the airbrushed pretenders on our magazine covers is a difference not of form but of function.

The ancient Venuses were fertility aids — good luck charms and fertility talismans — created in an era when having healthy babies was an act of survival. The fertility sculptures were something you carried around in an effort to intercede with the gods and ensure your future. Which is not the same thing as appearing on the cover of Paper magazine balancing a champagne glass on your arse.

For a sense of the real origins and purpose of the current craze for big backsides you can do no better than listen to the lyrics of Minaj’s big jungle hit, Anaconda. The scene is a car in which the possessor of a large “anaconda” has pulled up and is now happily banging away at Minaj, like “Mayweather with the jab” — a reference to the boxer Floyd Mayweather Jr — while delivering the song’s rousing choral climax, “My anaconda don’t want none, unless you got buns, hun”.

This isn’t about women. It isn’t about fertility or the sex war. I don’t even think it’s really about reclaiming America from the skinny Caucasian arse. Ultimately it’s about men. About pleasing them and catering for them: about achieving the dimensions to fit their big anacondas. So, yes, we have been treated to a cultural rewind with the shaking of Kim Kardashian’s ass. But it’s a regression that leads straight back to the same old starting point.

The buttocks might be doing the shaking, but it’s the lingam that’s doing the talking.