Guilty as charged. Yes, a few weeks ago, I did express the view on Twitter that I could not see the point of another Gilbert & George exhibition. “Haven’t they had enough shows?” I tweeted.

At the time, it was a sincerely held view. Regular readers of this column will know already that I am not, generally, an admirer of the tedious two. Really old readers of my output may even remember the time I was banned from the Anthony d’Offay Gallery for the heinous crime of writing un-positive things about them. As far as I know, I have never actually been unbanned. Perhaps this article remains artistically illegal. But I have to write it. Because Gilbert & George are doing something brave in their new display at White Cube Bermondsey. And it needs to be thought about.

For obvious reasons, contemporary art in Britain has been remarkably silent on the subject of radical Islam. As a working broadcaster myself, I know exactly how and why the mechanisms of self-censorship have achieved this silence. Unfortunately, fatwas work. Ever since the Rushdie affair first blew up, Islam has been a no-go area for reasonable cultural criticism.

So what Gilbert & George are doing in their new show — in which they melodramatically demonise the visual and atmospheric impact of radical Islam on the streets of London — is mentioning the unmentionable. Are they being reasonable in their attacks upon radical Islam’s aggressive visual presence? No. Have they ever been reasonable about anything in the past? No. Should we admire them for having the balls to treat Islam exactly as they might treat everything else? I think so, yes.

One thing this is not, of course, is a religious debate. Gilbert & George don’t do religion. Their art is about themselves: their tastes, their world-view, their visual surroundings. I like to think of them as a grotesque thermometer inserted into the rectum of urban Britain.

Back in the 1980s, when Margaret Thatcher was still our prime minister, they produced a suite of particularly unpleasant images of skinheads and their slogans that none of us liked, but that, it has to be admitted, captured vividly that Sink-the-Argies-It’s-The-Sun-Wot-Won-It mood of Thatcher’s Britain. Their current show is even fiercer. This isn’t so much a commentary on our times as a scream that never finishes. This is art with the presence of a burglar alarm.

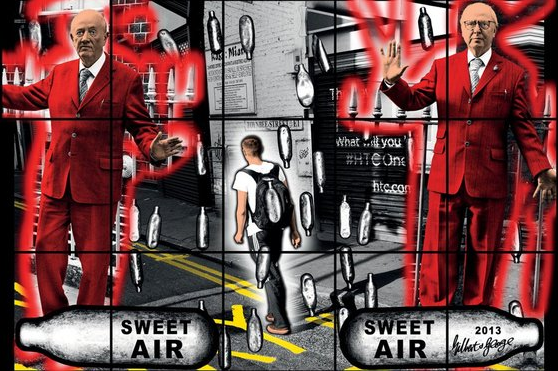

As often happens with G&G, a particular visual symbol has caught their eye and become the tone-setter for the rest of their anxiety. In this case, it is the small silver canister in which laughing gas — nitrous oxide — is bought and sold in the streets. The paperwork for the show tells us that laughing gas, “hippie crack”, has become the drug of choice down Gilbert & George’s way, and that they have been collecting the sinister little canisters, which look like miniature bombs, on their morning walks around their beloved East End. They have certainly collected a lot.

The silver canisters pop up in every picture. Usually in mountainous piles. Sometimes as sinister singles. Bombs, of course, have a particularly plangent historical meaning for the East End of London, a meaning of which the archly nostalgic Gilbert & George will be fully aware. All the way through this show, you feel, they are lamenting the fact that the bombed-out East End of old has turned into the bombed-out East End of today.

From what I remember of my visits to the dentist, “hippie crack” warps all your horizontals, makes the world appear hysterically funny and then knocks you out. At some point, the laughter turns into paranoia. Most of the photo-works in this hyped-up collection have a similar trajectory. Even by Gilbert & George’s standards, this is a very paranoid event.

The first picture you come to as you turn left into the exhibition’s first room is a view of London’s streets, in which a gang of hoodies has lined up before you to give you a good kicking. The sinister canisters that surround them — and fuel them — look exactly like unexploded Second World War bombs. A sign at the back says: “Stay Safe. Stay In.” A sign at the front says: “Welcome to London.”

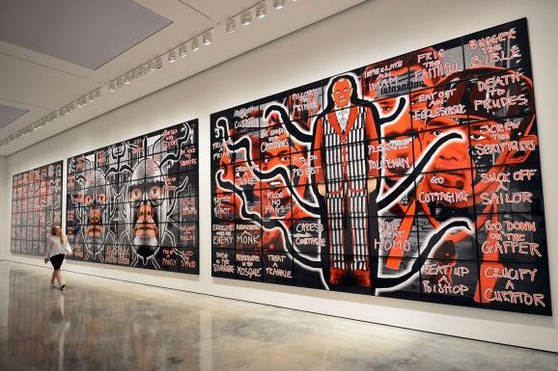

Full of druggy distortions and angry masks, looming faces and accusing eyes, coloured exclusively in satanic reds and hellish blacks, this rabid dog of a show features some of the maddest imagery G&G have ever produced. The paperwork tells us it’s a show about their beloved East End and what it has become. But in G&G’s art, the Queen Vic pub has always stood in for Britain as a whole. We are all EastEnders now. This is the world we are living in.

While the canisters of laughing gas throw one kind of flammable material onto the bonfire, the presence of radical Islam throws another. Picture after picture is dominated by the sinister black shadow of a woman in a niqab staring out at us through the narrow slit in her hood. They’re like faceless black chesspieces coming towards you down an alley. An invasion of black Daleks.

How are we to understand this spooky and dangerous imagery? Visually, would be my firm answer. In the world of symbols inhabited by Gilbert & George, the faceless black figures have become symbols of an invasive mood of aggression. In our world, the real world, the niqab raises issues of personal freedom: a woman’s right to wear what she pleases. But in the world of symbols, Gilbert & George’s world, what counts is visual impact. And in those artistic circumstances, the anonymous black figure staring out at you through a narrow slit is as welcoming as a tank.

Some commentators have taken the safe option and dismissed this edgy symbolism as “Islamophobia”. But a closer inspection of the imagery reveals a show that seeks to confront a set of charged and complex visual paradoxes. In Vallance Road, from 2013, a typical black figure dominates the centre of the street, but the artists themselves — in attendance, as always — have become twirling arabesques of Islamic script. The Islamic proscription against figures has created a human writing. Why, then, does the solid black woman remain so grimly intact?

Another artistic battle raging through these galleries is the battle of colours. In western art, black has traditionally been the colour of death. It’s what we wear at funerals: the colour of our widows. When the black niqab arrives in a world that holds those colorific values, it cannot help but send out aesthetic shock waves.

All this is dealt with in a pumped-up and relentless fashion. As always with Gilbert & George, there is far too much of it. As always, their preening and their pomposity are as jarring as the harsh urban circumstances they describe. As always, you leave the exhibition wishing they would make something other than the same old multipart photo-works they always make. But none of that stops this from being a particularly brave event.

Gilbert & George, Scapegoating Pictures for London, White Cube Bermondsey, London SE1, until Sept 28