Oh dear. While it would not be accurate to describe the eighth Liverpool Biennial as a turkey — no event that involves a visit to the exciting city of Liverpool can be entirely gallinaceous — it would be accurate to describe it as the worst so far, and to advise that the event needs to sort itself out. I write as someone who has seen all the earlier biennials. When it arrived on our calendar in 1999, it was answering a genuine cultural need. The 21st century was looming, yet Britain did not have a biennale of contemporary art. Istanbul had one. Taipei had one. Yokohama, damn it, had a triennale. But in Britain: nada.

Where, though, to put it? Every biennale needs an identity, a specific texture that distinguishes it from other such events. Liverpool found one quickly. Two features stood out. The first was the choice of artists. At most biennales, you encounter the same international art stars you encountered at the one before. If you missed them in Sao Paulo, you could catch up with them in Venice, then six months later at the Serpentine Gallery. Liverpool, however, avoided the stars. Instead, it searched out a fresh-faced international cast and involved it in shows that felt nimble and young.

The second advantage was the city itself: the Liverpool storyline. So much has happened here. When you walk through the city, you walk through such a plangent social history. I remember blundering up a hill at the first biennale and finding myself in a street full of burnt-out houses where I swear you could still smell the smoke of the Toxteth riots. The present show has a stab at involving itself in all that. Scattered around several venues, it sends you map-reading through Liverpool, and, providing you avoid the centre — which looks like a moveable backdrop to an item on The One Show — there is plenty of proper urban character to be encountered. Where the event goes wrong, very wrong, is in its guiding idea.

Whoever came up with the curatorial rule that biennales have to have a theme has a lot to answer for. The theme here is: A Needle Walks into a Haystack. That’s it. That’s the theme. For further illumination, I can only quote from the poster: “The artists in this exhibition… attack the metaphors, symbols and representations that make up their own environment, replacing them with new meanings and protocols: bureaucracy becomes a form of comedy; silence becomes a type of knowledge; domesticity becomes a place of pathology; inefficiency becomes a necessary vocation; and delinquency becomes a daily routine.” Now you know.

The main display has been mounted in what used to be the Trade Union Centre. The building itself — the haystack! — is a labyrinth of corridors, stairs and ruined rooms, through which you are encouraged to roam. It’s a characterful location. The problem is the art.

In the foyer, a battered ice machine that occasionally vomits new batches of cubes onto the floor turns out to be the handiwork of an artist called Norma Jeane. She — or is it he? — was born in California on the night Marilyn Monroe died. So she, or he, has adopted the Norma Jeane personality “and become an entity without a fixed body, gender or biography”. Michael Stevenson confronts us with a pair of plain grey doors, borrowed from the School of Computing and Mathematical Science, that stand in the middle of the room and demand to be walked through. The doors are connected to a computer setup in which different computer games are playing on monitors. If the games go one way, you can push the doors open. If they go another way, you have to pull the doors open. That’s all that happens.

Bonnie Camplin gives us a room set up for what she calls DSV Technology for the Deeper Observation of Small Objects. Before you go in, you have to put your name on a list and wait for an assistant in a white lab coat to summon you. That’s the good bit. Inside, a sequence of dicky psychedelic lights exposes you to phase two of this silly experience. For phase three, you are asked to stare at a small object of your own choosing for seven minutes.

What’s missing in all this grim pseudo-science is the thing you’ve come here to encounter: art. There’s no effort at encapsulation, no sense of summary or symbolism. No drama. No grace. The Liverpool Biennial, alas, has become a platform for curatorial pretension and not an occasion for public delight.

Of the 18 artists scattered about the haystack, only one is worth a second look. He’s Peter Wächtler, a German miserabilist whose self-piteous poems and songs provide the soundtrack to some dramatically hopeless cartoon imagery involving down-and-outs and rats. Disney meets Kafka in Wächtler’s art, sweetness meets bitterness, the Titanic meets the iceberg. If his output were edited down to a Disney length, it would become genuinely poignant.

Away from the main show, the shapelessness continues. At the Bluecoat Gallery, there’s an exhibition devoted to James McNeill Whistler, the notorious 19th-century Anglo-American impressionist. I am one of those who is largely unmoved by Whistler’s foggy views of Venice and London. If they had been produced in Japan, and not merely influenced by Japanese art, they would be classed as nihonga — kitschily atmospheric haiku-art, with lots of fog in it. But the real mystery is why an international biennale of contemporary art should suddenly detour itself to Whistler.

At previous biennials, there has always been some cheeky outdoor art scattered about the public spaces. I remember the transformation of a statue of Queen Victoria into a hotel for the night. And Richard Wilson’s extraordinary cutting up of an office block. Nothing as exciting as that happens here. Yes, the veteran Venezuelan op artist Carlos Cruz-Diez has “dazzled” a boat at Pier Head by painting it in coloured stripes. But that is more properly part of the national commemoration of the First World War. The absence of inventive public commissions is a conspicuous lack that contributes to a sense of inertia.

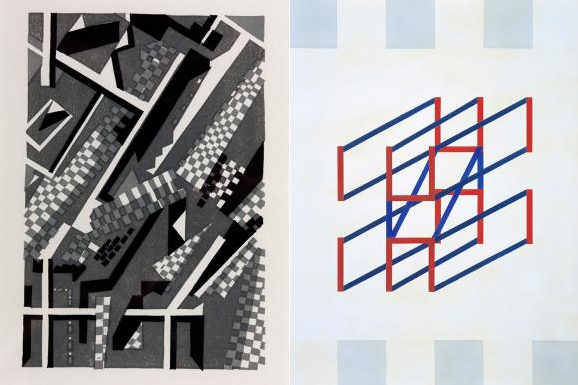

At the Walker Art Gallery, the John Moores Painting Prize, which predates the biennial and is always an interesting mixed bag, is — surprise, surprise — an interesting mixed bag. Only the inventive redesign of the lower gallery at Tate Liverpool by the veteran French architect Claude Parent can be deemed a success. Using ramps, chicanes and balconies, Parent makes you look at art from different angles. Literally.

By the time you reach the Parent display, the biennale quicksand has begun to harden into something almost graspable. We, it seems, are the needles, and the haystack is the multifarious world we inhabit. It’s an idea made most explicit in the film by Sharon Lockhart, showing at FACT, in which gangs of Polish schoolchildren in the city of Lodz amuse themselves by inventing street games in the grim post-communist courtyards in which they play. They ride their bikes through puddles. They make castles in the mud. They kick footballs.

Their feral creativity is reasonably interesting, although it, too, is observed for too long. Unfortunately, Lockhart undermines her insights by appending some dire back-of-the-envelope sociology to them. Citing the “influential Polish pedagogue” Janusz Korczak as her inspiration, she displays a set of pages from a Polish newspaper brought out for Jewish schoolchildren in the 1920s on a portentous white plinth, as if they were minimalist relics on an altar. I gave them a good read. They’re chiefly full of bad jokes. A professor of a zoology class asks his pupils if they know of any animals that cannot hear. A pupil puts his hand up. Yes, professor. Deaf animals.

This, then, is a biennial that has lost its way. Taken over by the curatorial classes, it has little to say to the people of Liverpool. It looks underfunded. And with the New Contemporaries exhibition not opening until September, there’s a clear sense here of not enough happening. It needs an intelligent shake-up. I recommend they beg Ralph Rugoff, the brilliant director of the Hayward Gallery, to take it on. Part-time, if need be.

Liverpool Biennial, until Oct 26