Upon hearing that Tate Britain was devoting an exhibition to Kenneth Clark, two big questions sprang to mind. The first was: why? Clark was a museum director, an art writer, a government go-to man and a TV presenter. He was not an artist. What qualifies him for an artistic examination at Tate Britain? The second question leapt off the shoulders of the first. What was Tate Britain actually going to show us? Would we get Clark’s writings in vitrines? His TV programmes on monitors? To be honest, reader, the pulse did not race at the prospect.

However, as soon as you walk in, all the doubts are challenged. Busy with stuff, the display plunges you immediately into the mess of art into which Clark was born, and in which he spent his 80 years. Here’s a Japanese screen. There’s a Landseer painting. And look, a Leonardo nude. From the off, the point is made, and made well, that Clark’s life was embedded in art.

Most of us know him best as a TV presenter. In the world of arts television, Civilisation, Clark’s 13-part telling of the story of art, is the elephant in the room. It is without doubt one of the most famous television series ever made. Extracts from it are playing at the end of the show, and I was struck, as always, by how little Clark actually says while the camera dawdles so effectively on these great sights. Memo to self: say less, show more.

Civilisation was first broadcast in 1969, two years after the Beatles brought out Sgt Pepper’s. Clark was born in 1903. So that leaves a very large and very significant chunk of his life — the best part of the 20th century — to probe and understand.

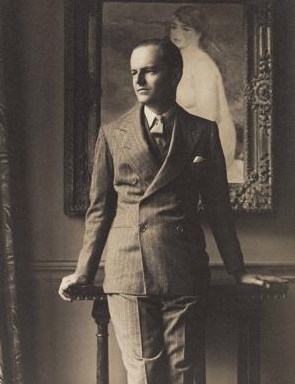

He was born into piles and piles of money. Amusingly, the Clarks had made their vast fortune in textiles by inventing the wooden cotton reel. But by the time they spawned Kenneth M Clark, our Kenneth’s dad, the family had fully completed its transformation from nouveau riche to idle rich. The first art we see here — a hunting otter, by Landseer; a view of Venice in the fog, by William Quiller Orchardson; two portraits of young master Kenneth, by John Lavery and Charles Sims — was the art that surrounded him as a boy in a vast country house in Suffolk.

It was his nanny, apparently, who nudged his taste in a less obvious direction when she took him to a selection of Japanese treasures at White City in 1910. With its radical simplifications and elegant exaggerations, Japanese art excited the seven-year-old Clark as nothing else had. He collected it throughout his career. At the other end of the show, in the selection of TV films he made in the 1960s, before Civilisation, there’s a particularly revealing one about the purpose of art. “One must say,” he drawls in that advisory MI5 voice of his, “that art gives us, those of us who appreciate it, a peculiar happiness that nothing else can give. I know it sounds ridiculous to those who don’t feel it, but there it is.” A peculiar happiness that nothing else can give. That sums it up nicely.

The messy mixes of objects — ceramics, carpets, bronzes, paintings; Chinese, Italian, wherever — with which he surrounded himself in his homes is another outcome of his country-house origins. And just look how the plum jobs began falling into his lap. After Oxford, at the age of 25, with no formal qualification in art history, he was offered the job of cataloguing the Leonardo drawings in the Royal Collection. At 28, he became Keeper of Fine Art at the Ashmolean, in Oxford. At 30, he became director of the National Gallery. A few months later, he was also offered the post of Surveyor of the King’s Pictures. That is not a career. That is a big win in Monte Carlo.

Surprisingly, perhaps, one of the least interesting walls here is the one showing us what Clark acquired for the nation as director of the National Gallery. His eye was conspicuously fallible. I cannot imagine how the four flimsy mythologies by Previtali displayed here were ever thought to be by Giorgione. So dodgy was this attribution, it prompted letters to The Times and questions in parliament. In another corner of the display, the 12th-century Coptic cloths he collected turned out to be 6th-century.

This shaky connoisseurship, allied with the frivolous and showy life he was leading at the time — swanning round Venice with his fashion victim of a wife; supporting shows from Mussolini’s Italy — do not paint an appealing picture of Clark in his thirties. Art may have saved him from becoming a full-grown Bertie Wooster, but the genes were definitely in him.

It wasn’t until the war arrived that he showed himself to be a man of mettle by securing the safety of the nation’s masterpieces in a Welsh mine and organising a series of daily piano recitals at the National Gallery that kept everyone’s pecker up. Something Churchillian had happened to his outline. However, the division between Clark’s public and private lives had begun to melt away. He had always been a private collector — on the evidence displayed here, he was significantly better at collecting for himself than for his country — but now this collecting spirit began to take on an aggressive public role.

The first sign of a more meddlesome involvement with our artistic destiny was his support for the Bloomsbury crowd. The chief appeal of the Bloomsberries was that they were not abstract artists. Clark had come to believe that abstraction was a dead end; that British art needed to steer clear of it and maintain a defining relationship with nature. It was a view triggered by his passion for Constable and Samuel Palmer. The dislike of abstraction became the main thrust of his artistic thinking.

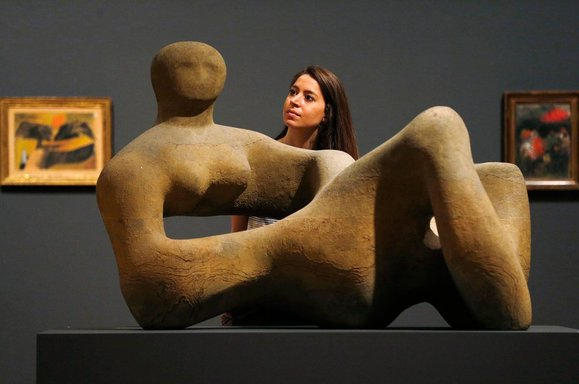

Having dallied with the Bloomsberries, he turned next to Graham Sutherland, John Piper and Henry Moore — what we now call the neo-Romantics. All were artists whose iconography originated in the natural world. Clark bought their art, championed them privately and publicly, and tweaked the rules of directorship to ensure his views prevailed.

When the war broke out, he was made chairman of the War Artists Advisory Committee and proceeded to give all the work to his favourites. In a scheme called Recording Britain, the extraordinary proscription was laid down that art commissioned by the government had to be in that most traditional English medium: watercolour.

All this the show describes for us with a happy assortment of art and documentation. Legible, insightful, unafraid of judgment, it’s an adept display of exhibition-making by Tate Britain’s best curator, Chris Stephens. The extent to which art shaped Clark’s life is exciting and precious. But the success he had in shaping Britain’s cultural presence is also alarming.

Should any one man ever have this much power again? No.