Everybody loves a small museum. It’s not that the big museums — the Louvre, the Prado, the Metropolitan — are not filled with marvellous things. They are. But art is a delight that should never be slogged around. For art to work properly, it needs intimacy. Hush. So give me a small museum any day. And in this respect, London is obscenely well stocked. Its inhabitants should dance a jig of joy every morning at what we have on our doorstep. (Memo to self: dance a jig of joy tomorrow!) Collections such as the Dulwich Picture Gallery, the Wallace, the Soane and the Foundling Hospital offer world-class art experiences in excellently compact proportions. If I had to select one of these smaller hoards as my favourite, it would have to be the Courtauld Gallery in Somerset House.

The Courtauld differs from most smaller collections in being chiefly devoted to impressionist and post-impressionist art. They have some fine Rubenses, some decent Renaissance art and a most intriguing William Dobson, but it is the impressionist and postimpressionist art that gets you jigging. The Courtauld owns Britain’s best Manet, Van Gogh’s most poignant self-portrait and the largest British selection of Cézannes. Above all, it owns a gathering of Gauguins for which a man might be tempted to swap his grandmother. In my case, the decision would be instantaneous. Goodbye, Granny.

In a new initiative, the gallery has begun focusing on choice parts of this postimpressionist collection and treating them to a special inquiry. The first of the special selections focuses on Gauguin. A small but riveting display brings together all the works by him the gallery owns, woodcuts as well as paintings, and reunites them with the pictures that used to belong to the gallery’s great benefactor, Samuel Courtauld, but which he, unaccountably, sold. We also learn about the pictures Courtauld had a chance to buy but didn’t. Chief among these is Gauguin’s definitive artistic statement on the meaning of life: Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going? I had never realised this huge, strange masterpiece, now in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, could easily have ended up at the Courtauld Gallery. A small box of tissues placed specially for weeping visitors might have been handy here. But hush, Waldemar, stop your sobbing, because so much that is marvellous did end up on Courtauld’s walls. The show retells the life histories of all his Gauguins and delves also into the artist’s changing reputation in interwar Britain — the period when Courtauld was buying — when a strange tugging commenced between the collectors who loved him and the art historians who suspected him. It’s a tugging that doesn’t really seem to have concluded. Poor Gauguin is never going to be allowed to shrug off his reputation as an escapist pleasure-monger, is he? Even this summary of his achievements surprised me with its hesitancy.

Fortunately, art critics don’t have to follow art-historical rules, so I am free to gurgle and throb at these exciting sights. It turns out that Gauguin was always the most expensive of the postimpressionists. When Courtauld, who made his money in textiles, began collecting his work in the 1920s, the sums involved were already dramatic. The first painting Courtauld acquired, The Haystacks, painted in Brittany in 1889 before Gauguin’s notorious departure for Tahiti, shows a cluster of Pont-Aven peasants raking and gathering a gorgeous expanse of yellow, which began life as a depiction of hay, but which Gauguin magics into a glacier of buttercups. Was there ever a better user of yellow than Gauguin? No.

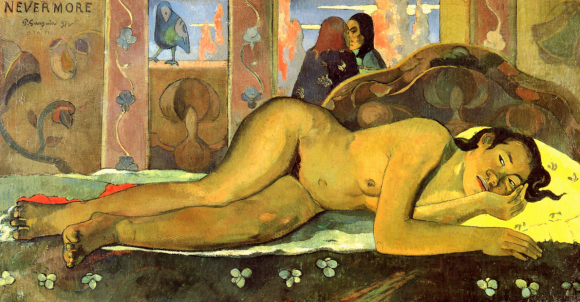

For an even finer example of his perfect appreciation of yellow, examine Nevermore, the mysterious Tahitian nude that I have several times nominated my favourite picture in London. Painted in Tahiti in 1897, on his second visit to the island, it shows his young Tahitian bride, Pau’ura, lying on a bed in the dark, frightened by the night. Behind her, a pair of mysterious figures continue their sinister whispering. On her window, an ugly black bird has landed and surveys her silently. By giving the picture an English title — the only time he did so — Gauguin makes an immediate atmosphere-grab for the mood of Edgar Allan Poe’s poem The Raven, whose doomy chorus of “Quoth the raven, ‘Nevermore’ ” is repeated so often and so inexplicably.

A few years ago, Nevermore was voted Britain’s most romantic painting by a group of art worthies who must have been looking at it with their eyes closed. Because what Gauguin is painting here is fear: a young girl’s fear of the night and, by extension, humankind’s fear of the unknown. What makes the image work, what lifts it into the realms of perfect visual poetry, is the lemon-yellow pillow on which Pau’ura’s dark and frightened face has been silhouetted. That one bright note in a picture filled with darkness turns this into a symbolic masterpiece.

Nevermore is a more haunting image than the Courtauld’s second great Gauguin, Te Rerioa, or The Dream. This show contains just the right amount of documentary back-up — not much! — and there we learn that Courtauld was encouraged to buy Te Rerioa by the pushy art critic Roger Fry, who considered it to be Gauguin’s finest work. Two Tahitian women are sitting in a hut, guarding a baby sleeping in a cradle. On the walls of the hut, a sequence of mysterious images — frescoes? carvings? — seems to show a frightened man grasping a naked woman above a frieze of simplified jungle animals. The man and woman are surely Gauguinesque approximations of Adam and Eve, whose job in the hut is to shatter the air of innocence that surrounds the sleeping baby and pollute it with the sweaty odour of sexual guilt. Certainly, Te Rerioa is another fretful, whispery, problematic Gauguin, one that should never have been mistaken for a Tahitian idyll. Once again the huge expanse of yellow that shapes the walls and floor of the hut constitutes a sensational display of inventive colouring.

Altogether, Courtauld acquired five important Gauguin pictures, as well as an unlikely marble bust of his Danish wife, Mette, carved after a mere handful of lessons from a sculptor of funeral monuments who lived nearby. It’s an astonishingly accomplished piece of carving. In terms of raw artistic talent — talent in the fingertips — Gauguin was up there with the Picassos and the Michelangelos. Congratulations to Courtauld for realising this fully before anyone else in Britain.