Now Lowrys hang upon the wall

Beside the greatest of them all

And even the Mona Lisa takes a bow.

Brian and Michael predicted it all. Back in 1978, their dreadful song about LS Lowry, Matchstalk Men and Matchstalk Cats and Dogs, got to No 1 in the pop charts and stayed there for an eternity, droning on about kids down our street wi’ nowt on their feet, who, a couple of verses later, were popping up in sparking clogs, getting painted by Lowry. Actually, looking it up, I see that Matchstalk Cats and Dogs was only No 1 for three weeks. It merely felt like an eternity.

Anyways, Lowry is now, indeed, hanging upon the wall beside the greatest of them all, in a prestigious re-examination at Tate Britain that is so full of paradoxes, it’s enough to turn your sparking clogs into Jimmy Choos. What ought to be a simple matter — deciding whether or not Lowry was any good — has become a complicated tiptoe across a cultural minefield dense with explosive class issues and huge art-historical power plays.

Where to start with the paradoxes? Perhaps with TJ Clark and Anne M Wagner, the two curators brought in to shape this reassessment of LS Lowry. What a lot of initials for one rethink. Clark is probably the most celebrated British art historian currently at work in academe. Wagner is one of America’s pre-eminent feminist reappropriators. She lectures on the feminist history of American modernism. He specialises in French 19th-century art. Getting these two to curate a Lowry show is like making Harrison Birtwistle a judge on Britain’s Got Talent.

Two such lions of contemporary art history were never going to come up with a straightforward journey through Lowry’s career, from beginning to end. So, instead, we get a typical Tateish lurch from theme to theme, which borrows its title — Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life — from the French poet Charles Baudelaire and seeks to present Lowry, it says here, as a pre-eminent recorder of “the dull catastrophe” that is Britain’s “post-imperial, post-Industrial Revolution condition”. So to all you reductivists out there who had him down as a painter of matchstick men — yes, Status Quo, I’m thinking of you — I have just one thing to say: sur ton vélo!

In his celebrated response to the 1863 Salon exhibition in Paris, Baudelaire called for “a painter of modern life” who would rescue French art from the Salon’s stultifying influence and paint the world as it was. The argument presented by Wagner and Clark is that, a century or so later, in Salford, Lowry answered that call and created an art that described, for the first time, the true bleakness of the industrial world. What’s more, they continue hopefully, not only did Lowry record “the swamps and chimneys” of industrial Wigan in 1925, his art can also be understood oracularly as a description of “the edges of Shenzen or Sao Paulo in 2013”.

We begin with a greatest-hits display drawn from all corners of his career, which seeks to summarise his achievements. Unfortunately, this mixing up of all Lowry’s dates has the immediate effect of making lots of things unclear. Thus, a foggy 1927 painting of some kids coming out of school looks across at an even foggier mill scene from 1971. Half a century separates the two images, yet stylistically and thematically they are all but inseparable.

One of the better paintings in the opening display, from 1953, shows the crowd surging busily to Burnden Park to watch the football. But, a few pictures along, a single pot of flowers in a terrace window, from 1956, attempts to evoke the opposite sensation: a monumental moment of urban loneliness. Alas, the latter is not a good painting. Depending too obviously on thick black outlines to achieve the intended sense of isolation, it’s as unsubtle as a clown’s make-up.

Upping the confusion, the second room tries to give Lowry an unlikely Parisian past by comparing him with Van Gogh and Pissarro. It’s a very bad idea. Van Gogh’s tiny view of the urban wasteland at the foot of Montmartre is immediately juicier and more eloquent than any of the stiff black outlinings with which Lowry has been spelling out his squalor. Pissarro’s sunshine, meanwhile, brought an immediate spring to my step at the sheer relief of encountering a different urban mood. It’s true that Lowry’s teacher, Adolphe Valette, was a transported Frenchman who came to Manchester in 1905 to paint the fogs, but Valette was a lyrical melancholist who found a Whistlerish beauty in the toxic blues of Manchester’s sky, while Lowry’s vision is too monosyllabically glum to find beauty anywhere.

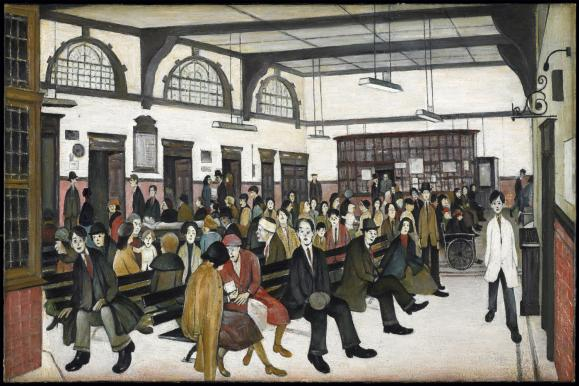

Having made its unconvincing French comparisons, the show now enters its dullest phase, a long, repetitive slog through the heartland of Lowry’s career, made to seem duller still by the whining of George Formby on the loudspeakers, singing about his dad. What starts off as a bit of mildly appropriate atmosphere-setting grows quickly into a form of audio waterboarding as Formby and his song refuse to cease. What actually becomes clear is that, as a painter, a mark-maker, Lowry was relentlessly one-dimensional and limited. In parti-cular, he was an awful summariser of people. Here’s a painter who sprinkles crowds into a scene like someone putting pepper onto a boiled egg. The shorthand he uses for dogs is even uglier. It’s an effect exaggerated by the unshiftable white grounds across which these ugly silhouettes keep scuttling. Where in modern life did Manchester’s pavements become as white as a snowfield in the Himalayas?

Something else that’s unpleasant is the sense of judgmental distance he maintains: the air of overlordship. Lowry, you feel, the rent collector by day who painted by night, is seeing the world as an ant farm across which hordes of interchangeable human ants are perpetually scuttling. There’s a visual cruelty to much of the imagery, and precious little warmth.

All this is disappointing, but hardly surprising. The Lowry who emerges here is the one we’ve always known about: repetitive, drab, overstylised and professionally northern. The big idea presented by Wagner and Clark — that he was a pioneering tragedian whose art not only described the grim reality of the industrial world around him, but also predicted the creation of the post-industrial badlands of the world ahead — is surely a case of wishful thinking. Having met Lowry on a couple of occasions when I was a fledgling art writer dreaming of working for the Manchester Guardian, one thing is certain: the old curmudgeon would be guffawing himself silly at the spectacle of the multi-initialled Clark and Wagner hopping through all these art-historical hoops as they seek to endow him with international clairvoyance and turn him into a Baudelairean hero.

Fortunately, the show has one genuine moment of revelation up its sleeve. The final room brings together the five large panoramas Lowry painted in the early 1950s as a result of an Arts Council commission for the Festival of Britain. These late panoramas are by some distance his finest works. Forced to adopt an epic scale, his art finally acquires genuine width and heft. The matchstick men are now so small they barely count. Lowry seems finally to have noticed the apocalyptic grandeur of the despoiled northern landscape he’d painted so often.