Let me put my cards on the table: I don’t think the Victoria and Albert Museum should be putting on exhibitions devoted to David Bowie. And before thousands of angry middle-aged trolls with spiky haircuts and platform heels turn up in my Twitter account to give me a good kicking, let me add that it’s not because I don’t rate him or appreciate his music. Bowie is unquestionably one of the most brilliant and influential performers of modern times. His music has supplied the soundtrack for many a fractured British life, including important parts of mine. You’ll get no arguments from me about the scope of his impact, or its depth. My point is that he should not be having a show at the V&A.

Why? Because it’s an act of colonisation, that’s why. This is an event that should be happening at the O2 arena and then travelling to the National Exhibition Centre in Birmingham. There are plenty of places in Britain that would welcome and suit a David Bowie exhibition. There are not, however, plenty of places in which the importance of 15th-century German limewood sculpture can be appreciated, or the significance of Italian maiolica of the Renaissance. Only the V&A can do that.

It’s worrying, too, how obviously this show is part of a carefully engineered piece of promotional hype. Ever since the surprise appearance of that particularly careworn new single on January 8 — on the Today programme, of all places — a skilled puppet master has been pulling our strings with scary precision. The day I visited was the actual day on which Bowie’s new album reached No 1 in the British album charts, the fastest-selling album of the year so far. Should the V&A be helping David Bowie sell yet more records? Or should it be celebrating Donatello and opening our eyes to the wonders of Islamic metalwork?

As I said, none of these doubts concerns his actual contribution to music and fashion. Bowie may not have invented crazy stage costumes (check out the Little Richard video playing in the exhibition’s first alcove) and he certainly wasn’t the first cross-dresser in pop (look up what Mick Jagger was wearing at Hyde Park in 1969), but he was the main conduit through which these outré influences poured into Britain’s suburbs, and changed them. A rebellious suburbanite was speaking to the other rebellious suburbanites in a language they could understand and relate to. Here were lessons in alienation and angst coming, not from Hegel and Sartre, but from the Laughing Gnome.

All this is made vaguely clear by a chaotic and lively show that combines an impressive hoard of materials from Bowie’s personal archives — clothes, song lyrics, photos, cuttings — with bits and pieces of pertinent historical detritus from the V&A’s own collection. The result is simultaneously a look back at Bowie’s career and an exhibition that seeks to understand his impact — with lots of great music thrown in, lots of memorable videos, and plenty of state-of-the-art computer gadgetry.

Aside from opening up his archive to the V&A’s curators, Bowie himself has had no influence on the shaping of this show. Which is perhaps why it is sometimes so painfully pretentious. Watching the august Victoria and Albert Museum trying to get down with the kids and speak Bowie-speak is like watching a middle-aged auntie squeeze herself into a pair of purple hipsters. The curators have called their event David Bowie Is, a piece of verbal archness that echoes clunkily throughout the entire display. Thus, the different sections are entitled: David Bowie Is Not Yet; David Bowie Is Making Himself Up; David Bowie Is Where We Are Now. The temptation to add David Bowie Is Not Naff, But This Is welled up in me soon after I entered, but there was nowhere to scrawl it at an event that is largely virtual: a pulsing, throbbing mash-up of electronic effects, rousing soundtracks, snatches of sound and vision, collages, memos and memorabilia, all packaged into a crowded set of inchoate readings that appear eventually to conclude that David Bowie Is Many, Many Things.

The opening stretches are loosely chronological and feature a suite of atmospheric alcoves, in which faded ration cards and battered army papers fix Bowie’s origins in the gloom of postwar Britain. The year he was born in Brixton, 1947, as plain David Jones, was apparently one of only two years in British history in which more than 1m British babies came to earth. And, as the curators pointedly point out, a good number of those babies would also have been called David Jones. How to stand out from the crowd? How to be a David Jones who was different from all the other David Joneses? Those were, indeed, the questions. It’s a conundrum encapsulated neatly by a piece of new art commissioned for the show from James Yarker, featuring 1m grains of rice arranged palely in a window.

Bowie’s official education was surprisingly short. He’s renowned for reading a book a day, and one of the more coherent observations made here is that various lofty artistic insights entered suburban Britain through his work. Brecht. Weill. Artaud. I’ve always assumed he went to art college because those are the kinds of atmospheres that swirl around his madcap appropriations. But no. He left school at 16 and went to work in an advertising agency, where he obviously learnt quickly how to swap identities and promote himself.

A fascinating early wall shows him trying out new bands and new looks with the frivolousness of a Saturday shopper on Oxford Street. First he’s in the King Bees. Then he’s in the Konrads. First he’s David Jones. Then he’s David Bowie. This apprenticeship of many selves leads, of course, to an adulthood of many more. This isn’t the kind of show that makes any attempt to probe the deeper reaches of Bowie’s psychology, but it’s obvious enough that something darkly unfixed is driving him. His meeting with Andy Warhol, recorded by a Factory minion and playing here on one of the display’s countless monitors, is uncomfortable to watch: two awkward artistic presences yanked simultaneously out of their comfort zones by the simple human act of saying hello.

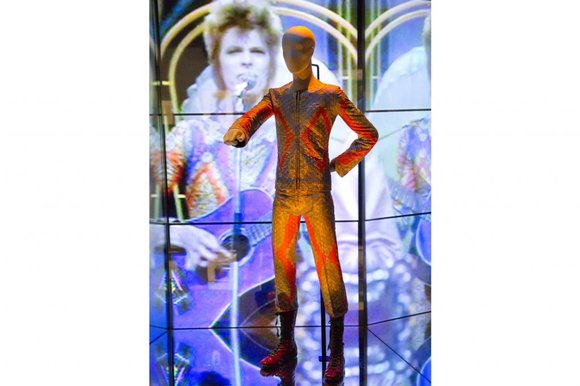

Having set him up as a rebel from the suburbs seeking a glamorous new identity, the display picks up energy and focus when it reaches the Ziggy Stardust years, the early 1970s, which it brings to life with an exciting assortment of costumes and sounds. There’s the original quilted jumpsuit he wore on Top of the Pops in 1972 for Starman; heavens but he was thin. There’s the original artwork for Hunky Dory and Aladdin Sane. And there’s the cover of Diamond Dogs, in which the top half is Bowie and the bottom half is a great dane.

Another section is devoted to the years in Berlin, where he fled from Los Angeles at the end of the 1970s to recover from cocaine psychosis, and to refind himself in the multilayered cultural context of the Cold War city. The result was a set of feeble paintings in the German expressionist style, followed by three musical masterpieces: Low, Heroes and Lodger.

Thanks to Sennheiser, you get a special pair of headphones to tour the show, which provide a travelling soundscape of music and interviews that follows you spookily from sight to sight. At every step there are never-before-seen valuables from the Bowie archives to examine. I particularly enjoyed the lyrics from his best-known songs scrawled on unimpressive schoolboy pages with an unimpressive schoolboy ballpoint pen. Ashes to Ashes becomes something very different when it is so furiously crossed-out and misspelt. Some hardened Bowie buffs may never be persuaded to leave the show, so packed is it with the personal and the private.

The final section focuses on his stage presence and his performances, which it presents to us in a mammoth video wall that goes all the way up to the gallery roof, and seems finally to dispense with the complex pretence that characterises the earlier stretches of the show. Why is Bowie so culturally important? Because he wrote Heroes, stupid. And Rebel Rebel. And Sound and Vision. And all those other pop masterpieces playing loudly in this fabulous giant jukebox, thinly disguised as a serious exhibition at the V&A.