You don’t often encounter an unknown Old Master on the exhibition trail these days. Partly because two centuries of relentless art history have sniffed them out already, but also because today’s galleries are reluctant to devote signature shows to someone nobody has heard of. Without name recognition, there can be no hype. Without hype, there are no blockbusters. Without blockbusters, there is no exhibition trail.

The arrival of Federico Barocci at the National Gallery can, therefore, be counted as a rarity. It would be untrue to say I have never heard of him, but it would also be untrue to claim I know anything meaningful about him. There are only two Barocci paintings in Britain, and one of those, the levitating Madonna at the Ashmolean, in Oxford, is a tiny sketch, leaving the National Gallery’s notoriously charming Madonna of the Cat to carry most of the burden for establishing and maintaining his British reputation.

There is another problem: Barocci’s dates. He was born in Urbino, Italy, in around 1533 and died there in 1612, which places him smack in the middle of one of the least tangible periods in the history of art. Too late to be a Renaissance artist, too early to be a baroque one, and not nearly twisted enough to be thought of as a mannerist, Barocci is a textbook inbetweener, falling through all the cracks. And most of his finest pictures are still in the Urbino area — another reason most of us know so little about him is that you need to drive up and down some very steep hills to find him.

The National tells us his story and proposes cockily that we view him as a precursor of the baroque whose art was doing baroque things 50 years early. The first picture here shows the Holy Family — Jesus, Joseph and Mary — pausing for a rest on their return to the Holy Land from Egypt. Mary has got down from a donkey and is collecting water from a pool. Joseph, looking unusually joyous for a Joseph, is handing a rosy-cheeked Jesus some fresh cherries gathered from a nearby tree. It’s idyllic and unlikely. And it alerts us immediately to a final reason why Barocci has remained so obscure: he’s too sweet for modern tastes. Even the donkey is cute. To see him for what he was — an extraordinary colourist, a brave designer, a draughtsman of genius — you need to peer through the surface sweetness to the stronger stuff beyond.

It’s a process that begins immediately here. Next to the Holy Family with the cute donkey, an adjacent drawing demands a rethink. To prepare for his Mary sitting by a pool, Barocci drew a nude study of a leaning woman. It was obviously done from life. The hang of her breasts, the plump bulge of her tummy, have no precedents in classical statuary. Nor is there anything in the Renaissance as physically tender as this. A real woman has posed for him, and her gloriously real body, recorded by Barocci with breathtaking fluency in softly coloured chalks, tells us loudly and clearly that we are in the company of an exceptional artistic presence: an artist defying his times.

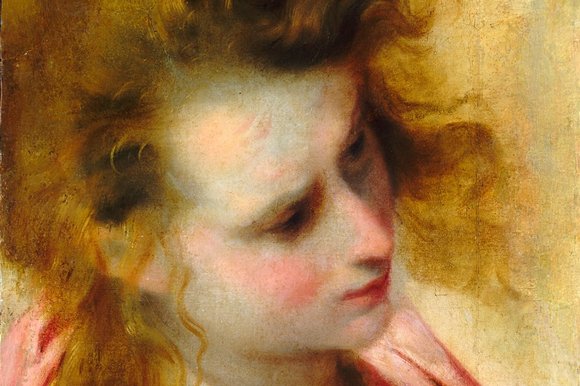

From here on, the show is a masterclass in sensuous draughtsmanship. With coloured chalks in his hand — a black for the outlines, a white for the fall of light, a red for the pinknesses of the flesh — Barocci is mightily impressive. The Queen has lent a head of the Virgin Mary to the show, which had me cooing audibly at the sensitivity with which the tones and textures of her skin have been evoked. First Barocci reminded me of Rubens, then he reminded me of Watteau, before finally I accepted that, with some chalks in his hand, he was as good as either of them — and he came first.

All this is made evident in a display that relates the drawings to the paintings in a particularly helpful manner. In the show’s central gallery, the drawings have been positioned in front of the large altarpieces they refer to, so you can look up from one to the other and make the appropriate connections. Another breathtaking drawing shows him trying out various positions for the Virgin’s hands for a large Annunciation that has arrived from the Vatican. Hands are notoriously difficult to get right, even for the finest Old Masters (stand up, Peter Lely, I’m thinking of you), but Barocci emerges as something of a digital specialist. It isn’t just the angles of the fingers he captures perfectly, but their colour, too.

So. Nobody will ever again underestimate the brilliance of his draughtsmanship. But a final opinion on the worth of his paintings is harder to reach. Sweetness is a quality the modern world only generally tolerates in washing-up-liquid commercials. And Barocci’s sweetness is doubly off-putting because it is so transparently Catholic. You don’t have to be a Presbyterian from Aberdeen to find his rosy-cheeked Virgins a bit too popish and his plump Jesuses a tad too cherubic.

This off-putting sweetness features prominently in the National Gallery’s Madonna of the Cat. As the only big Barocci in Britain, it is the picture most of us know him by. It shows the Holy Family relaxing at home, where John the Baptist has come round to play with his cousin Jesus. John clutches a fluttering goldfinch in his brilliantly observed podgy fingers and waves the poor bird in front of the Holy Family’s hungry cat, which is up on its haunches, ready to pounce. Jesus, who has been happily sucking at his mother’s naked breast, looks round to see what’s going on. What a plump, bonny, rosy-cheeked toddler he is. Not even that great softie Rubens, whom Barocci most certainly prefigures, ever came up with a baby Jesus as cherubic as this.

The big message of this show, however, is that we all need to look again. And the symbolic goldfinch with the red chest threatened by the hungry cat in the National’s picture is actually there to remind us of Christ’s terrible fate: the fatal truth that he was born to die. It’s clear, too, from the adjacent drawings that those particularly rosy cheeks of his are largely the result of changes in paint colour over time. The whites have paled, the reds have reddened, creating a false impression. In the adjacent drawings, the skin tones remain impeccably balanced.

Paradoxically, the other great discovery made by this show is what an inventive colourist Barocci was. Not one of the magnificent altarpieces gathered so adventurously from the churches of Urbino can be said to have a predictable colour scheme. Look at the outrageous yellows, purples and peachy pinks fluttering about the gorgeous kneeling Mary Magdalene in his Deposition from Senigallia. Or the sumptuous golden robe worn by the visiting Angel Gabriel in the Annunciation from the Vatican. I’ve been racking my brain to think of another Old Master who was as fond of yellow as Barocci, or as skilled at using it, and I can’t. That effect you get with raw silk, where it shines in one colour from some angles and another colour from other angles — cangiante, it’s called — is another speciality. Look how delightfully Mary switches from pink to yellow in the nocturnal Nativity from the Prado.

It’s intoxicating stuff. Although the show follows a broad chronology, there’s no pressing sense of development here. Rather, it feels as if an entire career is being unleashed at once. In historical terms, the end of Barocci’s time coincided with the arrival of Caravaggio, whose dark, realist revolution changed religious art across Europe. Remarkably, Barocci turns out to have been fond already of darkness and realism. An eerie nocturnal scene of St Francis receiving the stigmata from heaven in a spooky flash of gold, produced in 1594, is the most powerful painting here, and shows him to have been capable of top-class Caravaggism before Caravaggio.

He also did landscape drawings of unprecedented freedom and liveliness. And the show’s final room focuses on his portraits, which were uniquely strange. In most portraits of the times, the sitter’s eyes perform that old Renaissance trick of seeming to follow you round the room. Barocci’s eyes look through you instead, to the back of your head, in a weirdly unfocused fashion. This unusual eyeline plonks a forearm on the back of your neck and yanks you in for an intimate head butt, Glasgow-style. It’s an inspired ending to an inspired show.