If I had to choose one quality that distinguishes the important artists from their opposites, it would be this: being around at the right time. You can be immensely talented, immensely passionate, your imagination can bulge like a pufferfish with big ideas, but if you are over there when you should be over here, then none of it will matter. Nothing you do will ever feel crucial.

It works the other way as well. You can be entirely untalented, have wrists of wood and fingers of lead, but if you happen to be around when art really needs you, then even your crummiest daubs will have a currency. Which brings me to George Catlin. For reasons known only to those Dennis the Menaces of destiny, the Fates, Catlin was catapulted into the story of American art at a particularly significant moment. His portraits of Indian warriors and chiefs, painted in the 1830s and 1840s, turned out to be a witness account of a disappearing America and are now among the most prized possessions of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, cultural guardian of the American soul. They are treasured because nobody else left behind a record as evocative as this, and because the events surrounding the fate of the Native American Indian were to leave such a deep and immovable stain on American history. This is portraiture as record and as indictment.

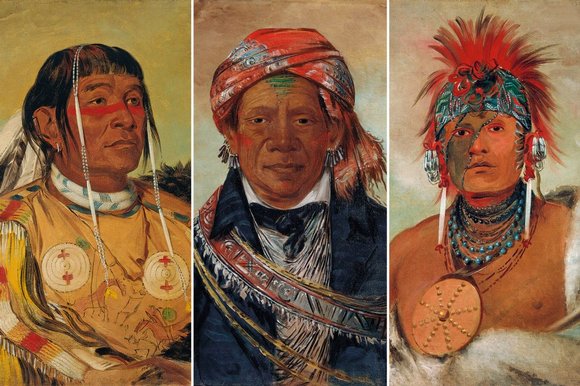

A selection of Catlin’s hugely influential Indian faces — we’re looking here at the invention of the bad guys in the fable of the Wild West — has arrived at the National Portrait Gallery in a show that had me recurrently thanking the rain gods for seeking him out. Catlin may never have been the most fluent or trained-up of artists, his figures are wonky and his compositions skewwhiff, but the art he produced was authentically unusual and brave. The Fates chucked him in at the deep end and he swam: the unlikely hero of a riveting tale.

The show actually begins with an amusing portrait of him, painted in England in 1849 by William Fisk. It features the fearless pioneer dressed for the prairie in beige buckskins, posing with his palette and brush in front of a large tepee. From the neck down, he’s the artist as hero. From the neck up, he’s entirely forgettable, a small, neat, ordinary paleface with a look like thousands of others. At the sight of him, the crazy idea popped into my head that Catlin himself could have profited from a Native American makeover. Compared with the shaved and bristling, reddened and blackened, pierced and punctured, studded and tufted gallery of fierce warriors he painted, he seems chronically unimpressive. This is a show that majors in anthropology, not psychology,but the juxtaposition of Catlin’s off-the-peg looks with the ring of dramatic humanity that surrounds him seems to say something telling about the attraction of opposites.

He was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, in 1796, and trained initially as a lawyer, like his father. However, the Fates had other plans for him. Having somehow developed a taste for art, he moved, at the age of 25, to Philadelphia, where he taught himself to paint in an endearingly amateur fashion. He never could do figures. Hands were usually beyond him. And his chief compositional idea was to stick an Indian in the middle of the canvas and paint him from the waist up. But his nation had just come into existence and was looking for an art of its own. And there was Catlin, with his hand in the air.

Nothing in European art is remotely like this unlikely gallery of Native American chiefs and warriors. No sitter in European portraiture had previously resembled Stu-mick-o-sucks, the proud chief of the Blood tribe, whose name translates as Buffalo Bull’s Back Fat, and who wore his long hair on either side of his face, except for a bit of fringe in the middle that came down onto his nose. Wee-sheet, whose name translates as Sturgeon’s Head, was a Fox warrior with handprints emblazoned across his chest, and a shaved skull with a bright red tuft on top of it.

A fierce tang of difference emanates from this exotic parade. Unencumbered by a European portrait tradition whose history stretched back to the Greeks, Catlin presents us with sights that have no pedigree. Buffalo Bull — the original Pawnee warrior, nothing to do with the long-haired circus sham of a similar name — has one black buffalo painted on his chest and another across his face. His heroic presence has been captured with a schoolboy excitement that not even two centuries of interracial friction can dim.

Most of the powerful faces here are smeared with red clay and glow like a Nevada sunrise. We’re not allowed to call them “Red Indians” any more, but Catlin’s portraiture makes obvious how they first acquired the unwanted name. It’s noticeable, too, that their wildly coloured tufts of hair, their studs, piercings, earrings and tattoos, look astonishingly modern. Many a kid in Camden would die for the spiky ridge of red that sits atop the shaved head of No-ho-mun-ya, whose name translates as One Who Gives No Attention. How did this scary anti-attentionist get his mohawk to defy gravity like that?

Catlin’s ambition to paint America’s disappearing natives seems to have been fired by two forces. The less noble of them was money. He was a Branson-style entrepreneur, a thinker-up of economic wheezes who would later tour England and France with his paintings, augmented by real, live imported Indians. When he first set off up the Mississippi in 1830 to record the tribes of the west, it was with an eye to creating an exotic gallery of Indian imagery to thrill and frighten the folks back east. And with its wonky perspectives and untrained hastiness, his art seems never to be straining for much in the way of depth. Yes, his unsmiling Indian chiefs have a fine nobility about them, but there is also the atmosphere here of a big collection of cigarette cards. In his first clutch of western journeys, Catlin visited and recorded 50 tribes. Later, searching further afield in the untouched north, he gathered 18 more. At the final count, his gallery of Indian portraits numbered 500, the best of which are here.

Yet there were also finer motives for his self-appointed task. The show argues, and the exhibits prove, that Catlin was genuinely moved by the plight of the native Indians. His wanderings across the badlands were a response to harsh new national laws demanding their removal from their eastern homelands and their forced relocation in the west. This precious record of faces and costumes, habits and rituals, had an ambition to preserve a world that was rapidly disappearing. When the Fates had their nutty idea to seek out Catlin, it was because someone was needed to record a moment of symbolic heft: the moment the white man stole America.

Just around the corner, in the National Gallery, another dazzling display of 19th-century American art makes clear what the landgrab was about. The landscapes of Frederic Church are usually small in scale but huge in mood. Set at dawn or dusk, in what TV cameramen call the magic hour, these enormous vistas and dramatic horizons feel as if they are a record of somewhere wondrous and biblical. When God created America, he created a landscape that was so easy to mistake for the Promised Land.