Typical. You wait and wait for an important Dada artist to be examined in depth in a significant retrospective, then two of them turn up at once. Dada being Dada, there is plenty of scope for disputes about whether Man Ray or Kurt Schwitters were proper Dadaists — some will feel that one was but the other wasn’t, or vice versa — but I propose to leave these unhelpful category arguments untouched and concentrate on the more serious question raised by these shows: which is why one of the examined artists turns out to have been a more substantial figure than we generally assume, while the other was less substantial. Indeed, he was an overrated bore.

Man Ray was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia in 1890. So he was an American and he changed his name. It’s not a good start. People who change their names are overly interested in issues of self-presentation. Fine if you’re a movie star or pop singer, but in a more serious creative field, the adoption of a snappy stage name is a mark of shallowness. Unless juggling with different personas is part of your creative presence. Which was certainly the case with Radnitzky.

As a Philadelphian Jew, whose father was a tailor from the Ukraine, Man Ray’s entire career can be understood as a piece of self-creation, a starting from scratch. The first important presence in the National Portrait Gallery’s engrossing examination of his work as a portrait photographer is, of all people, Marcel Duchamp, Mr Unfixed himself, who appears in a fabulous clutch of is-it-me-or-isn’t-it? images from the 1910s. First he’s a woman, his feminine alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, staring angrily out from the shadows as if spying on a husband’s adultery. Then he’s a back view, a faceless hairstyle with a huge five-pointed star shaved into it, in a picture entitled Tonsure. Finally he’s a naked Adam being tempted by a naked Eve, in a full-scale re-creation of a painting by Cranach. How much of this instinct for role-play is Duchamp’s and how much is Man Ray’s? We’ll never know. What is obvious is that a pair of kindred spirits had sniffed each other out in the crowd.

Duchamp arrived in America in 1915 to avoid the First World War. The two of them duly tried to set up a Dada group in New York, but, as Ray admits in a quote on the wall: “Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is Dada and will not tolerate a rival.” So he set off for Paris and arrived in time to join in fully with the mass escape from reality that was the 1920s. From here on, the show is a photographic tribute to one of the most desirable address books ever. In Paris, through Duchamp, the pushy Man Ray engineered access to everyone who was anyone in the interwar avant-garde. Gertrude Stein in her living room with Alice B Toklas; Picasso, Cocteau, Stravinsky and Satie; a splendid James Joyce, leaning forward and thinking with a fierceness that would shame Rodin himself; Hemingway, staring into space manfully.

It’s noticeable that the best sitters are those who act for the camera, while the worst ones are those who can’t. Give Man Ray a sitter with a taste for role-play, particularly if she happens also to be a beautiful woman working under an assumed name, and the photographic fireworks start immediately. Kiki of Montparnasse, whom he met in a Paris cafe in 1921 and quickly fell in love with, rifles through identities like a busy shopper at a jumble sale. There she is in a cafe, as big-eyed as Liza Minnelli. Moments later, her clothes are off and she’s become a human zebra, her skin striped enticingly by the shadows of a Venetian blind. Finally, in one of his best-known images, she turns her naked back on us, revealing the f-holes painted onto it that turn her into a full-length, full-bodied, irresistible female cello.

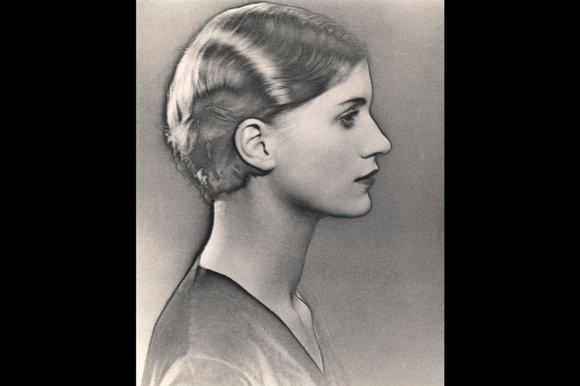

Women were his best sitters because dressing up comes more naturally to them, as does undressing. Confronted with someone like Matisse, who sits there stiffly like a tweedy country doctor, Man Ray appears bereft of ideas and insights. But when the beautiful Vogue model Lee Miller turns up on his doorstep, it seems to trigger a chemical reaction between photographer and sitter. The results would get my vote as the most enticing sequence of feminine portrayals in the whole of photography.

In a brave move, the exhibition-makers have included only vintage prints — prints Man Ray himself produced. Many are tiny. A few are big and glossy, in the preferred modern manner. The result is a constant switching in scale and tone, which emphasises his adventurousness and provides insight into his working methods. Sometimes the images are deliberately out of focus. Here he crops tightly, there loosely. This constant courting of accidents is the best thing about his photography, and the most Dada.

Like all really good shows, this one has a tangible final act. Alas, it tracks a creative decline that was probably inevitable from the start: you don’t fight your way up from a tailor’s shop in Philadelphia to say no to Coco Chanel and Elsa Schiaparelli. First the fashion world came calling, then Hollywood, then royalty. By the end, he is happy to photograph Wallis Simpson in a big hat, and make her look rich and thin. The tradesman has elbowed out the Dadaist.

At Tate Britain, Kurt Schwitters is treated to a duller investigation. He was born in Hanover in 1887, just in time to have his exciting modernist education disturbed, twice, by the most violent political upheavals of the 20th century. No wonder he became a Dadaist. Schwitters is particularly admired in Britain because he ended up living here and influencing the course of British modernism. Having fled from the Nazis in 1937, he turned up in Scotland and was immediately thrown into an internment camp on the Isle of Man. It’s a fascinating past and ought to have resulted in a fascinating show. But it hasn’t.

The big problem with Schwitters is that his most celebrated works — a set of giant installations made of household rubbish that he created in the houses he lived in, which he called his Merz works — have been destroyed. There are some photos and some minor remnants. The importance of the Merz pieces, however, has largely to be taken on trust.

In the absence of these house-sized achievements, it is left to his smaller things — paintings, sculptures, collages — to impress us. Because he was a churner-out by instinct, though, the collages in particular are too repetitive. And the show does him no favours by failing to arrange them in helpful clusters.

He tried his hand at landscape painting and portraits as well. Very badly. I’ve always been told this bad conventional art was something he turned to because he couldn’t sell his modernist works. This show insists it was actually an aesthetic choice. Here, then, is an event that successfully proves that Schwitters churned out too many dull collages, and that he couldn’t paint landscapes or portraits, either.