I feel sorry for Damien Hirst. That’s right. I feel sorry for Damien Hirst. In all my years as an art critic, I have never encountered as much raw negativity about an artist as the wave of grumbling and spitting that has preceded his arrival at Tate Modern in the first proper retrospective of his career. On Twitter, the trolls have been unusually busy giving him a kicking. He’s only interested in money, they gripe. His assistants make his art. He’d pickle his own wife for a buck.

Philippa Perry, the wife of Grayson Perry, tweeted me the opinion that Hirst was “an entertainer”, not a real artist. Her husband, meanwhile, who ought to know better, joined a queue of fellow practitioners keen to take a pop on other forums. “The most interesting thing about Damien Hirst,” said Grayson Perry from the stage of The Guardian’s Open Weekend, “is probably his accounts.”

Hirst’s lolly was always going to be the focus of all this snideness. A nation of shopkeepers cannot stop counting. Hirst’s demonic manipulation of the art market — even his fiercest enemies must surely acknowledge the highwayman’s skill with which he has encouraged the international rich to part with their profits — has sown a crop of envy so bushy, you can no longer see an artist behind it. Amusingly, the show ends in a shop with a difference. This one purveys limited-edition plastic skulls, signed by Hirst, for £36,800. Or you can treat yourself to a silk-screen butterfly print (£30,150). There’s something for everyone, even the impecunious, with keyrings at £7.70 and pencils for £2.05.

As I said, I went into this display at Tate Modern feeling sorry for him. When I popped out at the other end, however, I was buzzing. Take that, you shopkeepers.

The best thing about this event is its unwavering focus on Hirst the artist. All the other stuff — the lolly, the auctions, the assistants, the celebrity friends — has been snowploughed to the margins, leaving a clear view of an exciting and considerable artistic achievement. I loved the first room. It contains Hirst’s earliest work, dating from his student days, and much of what comes later is prefigured here in an endearingly wonky fashion. A big piece of student’s hardboard, propped up against a wall and splattered with coloured dots, turns out to be the first Spot Painting, produced in 1986. Later in the journey, the dots grow more precise: faceless, mass-produced. But for their energetic debut, the handmade, multicoloured blobs shove each other around the studenty hardboard like teenagers at the dodgems.

Also in the first room, and by no means devoid of this same joie de vivre, is a black- and-white photograph, taken in a mortuary, of Hirst posing with a head. Dating from his pre-London days in Leeds, it’s an unnerving sight. The artist grins maniacally out at us, while his dead partner in the double act — who bears an uncanny resemblance to Winston Churchill — gurns grotesquely, like a large man trying to squeeze himself through a small hole. An unquenchable interest in death is being unveiled, along with fine comic timing, learnt chiefly, you feel, from Alec Guinness in the Ealing comedies.

Every exhibit in this wonky opening room cocks a studenty snook at art’s past. The blobby Spot Painting seems to be the same size as the Seurats it mocks.

On the other side of the room, another row of dots has been painted on the bottoms of a range of saucepans: Sunday Afternoon in a Student’s Kitchen? Up in the corner, a range of cardboard boxes painted in bright household emulsions is a response to the sublime abstractions of the Russian suprematists of the 1920s: suprematism, the cardboard-box years.

The rest of this constantly lively retrospective features various branchingsout and enlargements, but underpinning everything that Hirst shows us from now on is this same pugnacious disregard for the rules. The walls of the art world are being scaled, you feel, by a cheeky monkey, who is laughing at the past, laughing at life, laughing at death, laughing at other artists, laughing at the Tate itself, and at its pious art-historical preferences.

On the previous occasion on which this much Hirstiana was unleashed on us, the infamous auction at Sotheby’s that sneaked through the gates of disaster on the day of the financial crash in 2008, I felt as if I was being carpet-bombed: how many Spin Paintings can a stomach stomach? Here, however, the Tate has kept Hirst’s profligacy under control by slamming down the portcullis and allowing in only key works and important developments.

Having set us off in a clear direction with its excellent opening room, the show never grows cluttered, and only begins to feel mildly repetitive with a few too many Spot Paintings. At the centre of the display, acting as a hub from which everything else radiates, is the celebrated shark-in-a-box from 1991: freshly restored and surprisingly sprightly. The sheer familiarity of this much-reproduced image has blunted some of the psychological impact of those razor-sharp teeth lurking in the tank, waiting to share their experience of death with you. But go round to the front, stare into the gaping jaws, and The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living, to give the shark his proper title, still has plenty of gallery bite left in it.

Hirst’s beasts in boxes were a response to the displays he remembered encountering in natural-history museums in his youth. They are partly about the beauty of the natural world, but mostly about the absurdity of existence. One of the criticisms levelled frequently at him is that he is mindlessly obsessed with gore and death, but I left this event feeling that the obsession is not with gore and death per se, but with the light they shine on life. To my eyes, the finest piece he has made is not the shark, but the gruesome tank with zapped flies from 1990, called A Thousand Years.

On one side of a glass vitrine, a stream of live flies emerges from a cool white box worthy, in its minimalism, of Donald Judd or Carl Andre. In the other half of the glass case lies the severed head of a cow,and above it hangs a fluorescent contraption for zapping flies. The contraption, too, is reminiscent of American minimalism, and particularly the fluorescent-light pieces of Dan Flavin. Against this perfectly designed minimalist backcloth, the flies enact their absurd dance of death. Moments after their birth, the unluckiest among them fly straight through the hole to the other side, where they are immediately zapped with a short, sharp electronic sizzle. And that’s that. There wasn’t even time to complain that life’s a bitch.

This nihilistic desire to laugh in death’s face positions Hirst among the Ensors and the Goyas: serious artists who make their dark points with comic means. At first sight, I imagined the huge black circle called Black Sun, which looms high on the wall near the end of the show, was a cheeky riposte to the celebrated rising sun that Olafur Eliasson evoked in the most successful installation to appear in the Turbine Hall downstairs. As you approach, however, the surface of Hirst’s blackness grows thick and creepy. Soon, you realise that the entire encrusted circle is made of dead flies, piled several inches deep, in a black pizza of death.

Every room in the show focuses on a different aspect of this comically nihilistic output. Thus, a parade of medicine cabinets, piled spectacularly high with pharmaceuticals, seems to mock our hopeless human reliance on packets of medicine. “Take, take me,” scream these evil-looking pantries, while In and Out of Love, from 1991, compares the brief life stories of the hundreds of live butterflies born in one room of the installation with the brief life stories of hundreds of cigarettes stubbed out in big ashtrays in the next room.

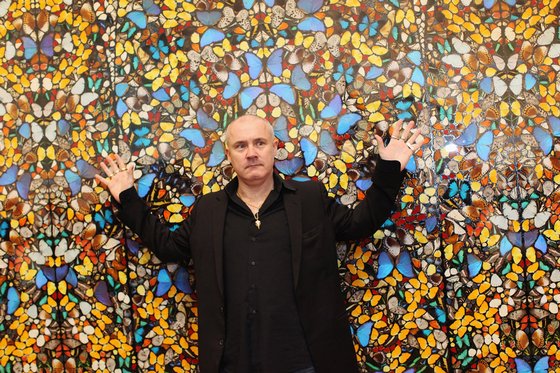

If the omnipresence of absurdist humour is the first of the show’s revelations, the second is Hirst’s impeccable sense of design. The reason he gets away with employing so many assistants — indeed, the reason he thrives on the process — is that he is such a skilled orchestrator of big effects. Everything here, you feel, has been placed, considered and coloured with an infallible eye for angles. One contender for the title of the show’s most beautiful space is the room where a set of huge butterfly collages mimics the colour effects of gothic stained-glass windows. A more surprising success is an over-the-top tribute to gold, diamonds and bling that seems to have been inspired by the taps in a sheikh’s bathroom. Wow. Where can I get that gold wallpaper?

Downstairs, in the Turbine Hall, you can see the controversial Hirst skull encrusted with £50m of diamonds, which is viewable here from two angles: the shopkeeper’s and the art lover’s. Shopkeepers can tut-tut-tut to their heart’s content at the price of all those diamonds. Art lovers can surrender themselves to the most gorgeous visceral experience available to diamond junkies outside of the Topkapi Palace, in Istanbul.

This is a notably successful exhibition. A career that can and has appeared repetitive and prolix is given a clear outline. Hirst the artist emerges at last from the bigger and fuzzier dust cloud of Hirst the celebrity. Where previously we imagined a merchant of doom, we now recognise an absurdist of cunning. And a piler-on of effects is outed as a superb designer. Well done, Tate Modern.