Iwas never keen on the Scottish artist Ian Hamilton Finlay. And he was never keen on me. In fact, this aggressive Scots loony seemed to hate me with enthusiasm. Once, he published a set of postcards showing my decapitated head lying at the bottom of a guillotine. Another night, coming back from the theatre, I found my front door plastered with stickers warning that I had been visited by the Saint-Just Vigilantes. They turned out to be a band of impressionable Scots art yobs — Finlay’s storm troopers — sent to terrorise others and defend his honour. My crime was the usual one of giving him a bad review. But, even though Finlay abused and threatened me, I enjoyed the fact that he was there, frothing at the mouth in his distant Scottish lair, caring enough about British art to wage insane wars over it. Nobody could ignore his presence.

Or so I believed until my latest visit to the Serpentine Gallery, where, for half an hour, I watched people doing just that.

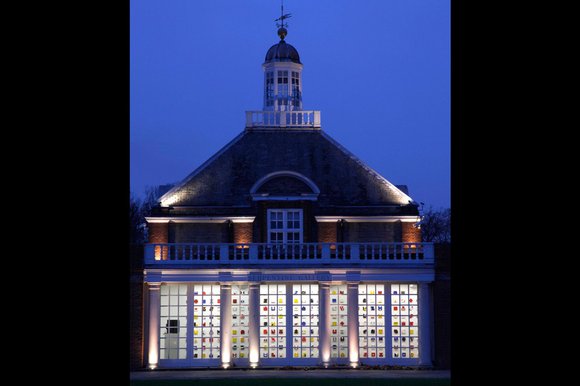

Let me explain. Outside the Serpentine, sunk into the tarmac by the entrance, is a large, round word sculpture by Finlay about the beauty of trees. It was put there in 1998 to commemorate Diana, Princess of Wales, who was a patron of the gallery and lived across the park in Kensington Palace. His word sculpture named all the varieties of trees in Kensington Gardens and added a lyrical woodland quote by the Scottish enlightenment philosopher Francis Hutcheson. All of which ought to have resulted in a resonant commemoration. Unfortunately, idiocy prevailed, and the Serpentine’s Diana monument is almost as useless as the notorious Diana water death trap across the road.

The chief problem is the location. Embedding something in the ground where anyone heading into the gallery is sure to miss it is silly planning. The other problem is its circular shape. If you do somehow manage to look down at exactly the right moment to spot Hamilton’s inscription, the only way to read it is to go round and round until you are dizzy. For the sculpture to work properly, the entrance to the Serpentine needs to be clogged up with scores of whirling visitors, circling themselves senseless as they block the doors. Think of health and safety!

Thankfully, nobody actually does that. For the half-hour I watched, not a single person noticed the Finlay piece. Although whoever put it where it is can feel good about their intentions, the work itself is only good, these days, for stepping on.

The point I am blundering towards is that crucial art point: connection. My new year’s resolution is to seek out more artworks that connect and to castigate more that do not. And going to the Serpentine Gallery, stepping over the invisible Finlay to view the feeble Lygia Pape exhibition inside, is good training for events ahead.

In this Olympic year, with big exhibitions opening relentlessly and wall-to-wall jingoism promised on every cultural front, our vigilance needs to expand.

The Serpentine is a good place to start, because the gallery’s offerings have been disappointing of late. Trying to work out why is instructive. Why is 90% of the Pape exhibition a waste of space? Why does so little of her art communicate anything worthwhile to us? Why is such a poor connection being achieved here? Why, indeed, has this exciting venue grown so dull? One reason is that Pape is a dead Brazilian, born in Rio in 1927 and dying there in 2004. At the risk of sounding like the unpleasant Finlay in his unpleasant prime, there is little in Pape’s background that can mean much to a British audience. I assume the newspaper headlines that pop up in the tiresome videos playing in the show’s opening space refer to plangent moments of Brazilian politics, but they were all Greek to me. And if you do not speak Portuguese, how can you possibly savour the subtleties of the untranslated soundtrack that accompanies the extra-large film focusing on salivating close-ups of Brazilian mouths? It seems to be an exploration of the oral confusion between greed and lust. But shoving the images in front of us with no effort to locate them is as useless as embedding a word piece by Finlay in the tarmac outside a gallery.

The display manages to grow steadily worse, with a silly film about a vampire in a black cape who roams around Rio biting people and reading copies of The Hulk. At one point, a man with a cross pops up and forces the bearded vampire, who looks like Russell Brand in a cloak, to retreat behind a curtain. Perhaps some sort of artistic attack on the role of the church in Brazilian politics is intended, à la Goya. Who knows? By the time we reach the vitrine filled with poetry — working in different media was apparently one of her main artistic aims, but if you’re reading this up there, Lygia, trust me, TONGUE I LICK MYSELF EXHAUSTIVELY is not a good poem — all but the most hardened Pape nuts will have had their enthusiasm crushed.

One work alone survives this trial by mistranslation: the installation preserved behind thick nocturnal drapes in the Serpentine’s central gallery. Called Web, it consists of a dark space that appears to be crisscrossed by rays of gold, like the intersecting beams of a searchlight. A closer inspection reveals these delicate golden beams to be lines of piano wire stretched at angles across the dark, and moodily spotlit. It’s a magical effect and needs no translation to work.

The first time I saw this installation, at the Venice Biennale in 2009, where it greeted visitors to the main international exhibition, it was even more effective because it was set in the cavernous darkness of the former navy warehouses of the Venetian republic. In those huge Venetian spaces, it felt downright apocalyptic. The Serpentine’s version is smaller, neater, tamer.

I mention Venice here not to show off about going to the biennale, but to make clearer where this kind of show originates. The Serpentine specialises now in displays that begin life on the international biennale circuit: air-miles exhibitions. It’s a regrettable development, because these trophy shows have no inherent, home-grown reason to happen. They might be curatorially prestigious and internationally au courant, but they don’t connect.

When the Serpentine’s director, Julia Peyton-Jones, took over in 1991, she swiftly made her mark with Broken English, an exhibition featuring a bunch of whipper-snapper British artists who had recently emerged from Goldsmiths College, led by the particularly noisy Damien Hirst. These artists all went on to have big careers, and to figure in milestone events such as Sensation at the Royal Academy. But the Serpentine found them first. And who can forget that Cornelia Parker display of a few years later, with Tilda Swinton sleeping in a glass box for a week, like a modern-day Sleeping Beauty, demanding our examination? These were not international trophy shows picked up at glamorous foreign biennales. These were home-grown events that changed the course of British art.

The rot seems to have set in in 2006, when Peyton-Jones, who is undoubtedly one of the most brilliant presences in the British art world, and who ought to be a shoo-in for the Tate job when Nick Serota’s fingertips are finally prised away from the lever, hired Hans-Ulrich Obrist, the Zurich-born supercurator, as co-director. Obrist is a delightful man who has published enough books to carpet a Turbine Hall installation, but, like most fashionable European curators, he doesn’t get British art. A typical Obrist show will read terribly well in the international art press, but it will change nothing here. It won’t connect.

So my message to Peyton-Jones is simple and clear: you have to go it alone again, Julia. The nation needs you.