The gob is smacked. Rarely have I left an exhibition feeling so fully confronted by its subject. There is much that is transfixing in the V&A’s celebration of the Cult of Beauty, and nearly as much that is silly. Rarely, too, in recent times, has so much artistic produce been unrolled for us that is so politically disastrous, let alone incorrect. Yet, if an exhibition’s task is to tackle its subject fully and atmospherically, then the V&A’s examination of the aesthetic movement must be rated a notable success. If you are not sure what the aesthetic movement was before you enter this display, trust me, you will be sure when you leave.

The task here is to understand roughly 40 years of British creativity, between approximately 1860 and 1900, during which most of the existing aesthetic values of the Victorian era were challenged. Initially, the tiny conspiracy involved a few pre-Raphaelite painters wanting to live their lives differently from those around them, and to decorate their houses differently, too. By the time the first world war took a final sledgehammer to their flamboyant hopes and outrageous tastes, those hopes and tastes were universally familiar. What began with Rossetti wanting to fill his bedroom with Chinese porcelain and his best friend’s wives ended up, a couple of decades later, as Liberty & Co.

Those of us who have previously had difficulty taking the aesthetic movement seriously — by which I am confident I count most people — have been put off chiefly by its decadence and its absurdity. One glimpse of the emblematic poet Algernon Swinburne, with his shoulder-length blond curls, his velvet smoking jacket and that look of adolescent rapture welded onto his unlined Victorian face, is all it ever takes to make this entire artistic effort feel ridiculous. A single line of a Swinburne poem, any Swinburne poem, persuades us that the poor man should be sent to bed with an aspirin and a cup of cocoa. “Her gateways smoke with fume of flowers and fires/With loves burnt out and unassuaged desires” springs to mind. Who is going to tell Algernon he should have gone to Specsavers, and that that is not a gateway?

The V&A show, however, understands aestheticism from the opposite bank — not from the easy-to-adopt position of the cynic, but from the altogether more useful viewpoint of the artistic historian. The argument put forward here is that Britain in the 1860s was a ghastly place to be. Soul-destroying. Pleasure-crunching. Toxic. Capitalistic. Soci ally rigid. Aestheticism is presented here as an enterprising mutiny mounted by beauty against repression.

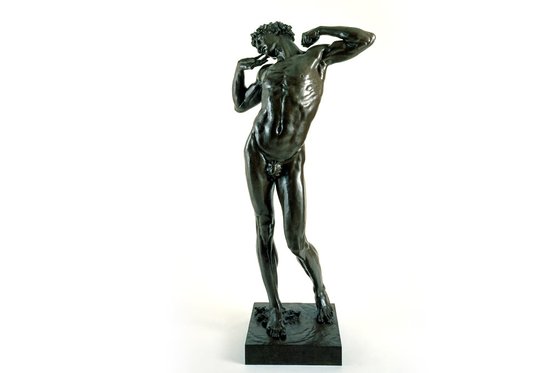

The first object you see — and it is an inspired choice — is a statue by Lord Leighton, called The Sluggard, of a naked athlete languidly stretching his arms above his head as if he has just woken from a long siesta. Legend has it that the pose was struck naturally by Leighton’s favourite Italian model between sessions, and that Leighton noticed it and decided to immortalise it. Sculpturally, The Sluggard seems to challenge every ethical given of the Victorian era: the meaning of work; the pull of duty; the need to keep up appearances. None of those matters a fig if a beautiful man cannot have a good stretch after his siesta.

Leighton’s perfectly envisioned tribute to laziness is joined in the agenda-setting opening moments of the show by a cluster of artworks celebrating the beauty of nature when she is trying to prompt some immediate sexual chemistry: a plaster relief with peacock feathers by Burne-Jones, some firedogs based on sunflowers by Thomas Jeckyll and a gorgeous peacock plate by William de Morgan. Siestas and peacocks — the aesthetic movement was not so much a challenge to Victorian values as a stamping down on them. There is something brutal about this showy nay-saying, something fierce. Were this to be happening today, you feel, one of the happy-slappers would be recording the attack on their mobile.