As I left the Bruce Nauman retrospective at Tate Modern, a noisy question was rattling round my brain like a stone in a can: how did Nauman organise the arrival of Covid-19 and the relentless social disruption it has caused to frame his work so perfectly? How much did you pay the gods, Bruce?

The first work you see by him at the bottom of the Tate elevator is a video piece of a pair of hands being vigorously washed, as if something crucial depended on it: they soap, they twist, they go between the fingers, splash, splash, splash. It’s the new way of washing hands, not the old way, yet the work, called Washing Hands Normal, was made in 1996.

Nauman was born as long ago as 1941 in Fort Wayne, Indiana. Can’t say I know the place, but I imagine it to be one of those bland Midwestern mall towns that American creatives are always keen to flee. From 1960 to 1964 he studied maths and physics at the University of Wisconsin. He then moved to California, where art turned his head. By 1966 he was teaching it in San Francisco.

In 1979 he moved to New Mexico, where he has lived ever since, one of those confusing American artists who bash out delicate visual poetry from humble stuff they find lying around the yard. Better art critics than me — lots of them — have had a go at defining what he does, without success. So here’s my dumb limey offering: minimalism in a dirty T-shirt.

Mind you, it’s hardly surprising there has been so little consensus. What a bewildering array of gifts he offers us at this darkly brilliant event. Nauman makes videos, he makes neon pieces, he performs, he bashes out no-nonsense quotidian sculpture from concrete and steel. And he keeps baffling us.

At the top of the Tate elevator, outside the exhibition itself, on another pair of stern video monitors a black man and a white woman are having an argument. “I was a bad girl, you were a bad girl, we were bad girls,” the woman goes. “I am a virtuous woman, you are a virtuous woman, we are virtuous women,” the man says. Black v white. He v she. Reality v unreality. Even the relentless aggression of their babbling feels contemporary. Yet the piece was made in 1985.

The show looks back at Nauman’s 50-year career, but doesn’t feel like a retrospective. That’s because it tangles up his chronology and attempts, instead, to group his produce into four meaningful clusters, described by the Tate’s curators in the catalogue as “rotation, manipulation, suspension and limitless space-time”. Ignore them. They’re just curators being curators.

Back on planet Earth, in the show itself there is no limitless space-time, just a succession of powerful slabs of Nauman in which he swaps techniques, changes methods, explores materials, alternates moments of peace with bouts of heavy slapping, and never lets up in a madcap journey of artistic exploration usually set in darkness.

“My work comes out of being frustrated about the human condition,” he explained in 1988. “And about how people refuse to understand other people.” Fretful minimalism for the midnight hour?

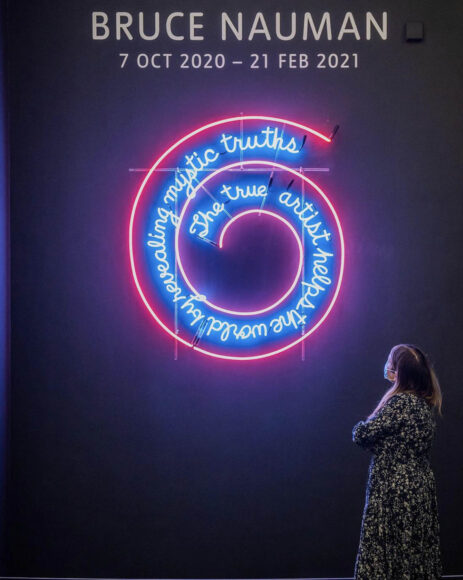

What is immediately tangible is how influential he has been. It’s most obvious in the neon pieces that stud the show. Nauman started working with neon in 1965, using it to make a slippery word-art that keeps switching meanings. EAT, says a green neon sign, before changing to blue and saying DEATH.

In his neon masterpiece, a towering wall of words that flash on and off, he compares a column of death — OLD AND DIE, STAY AND DIE — with a column of life: OLD AND LIVE, STAY AND LIVE. The seedy urban medium of neon has been salvaged from the world of strip clubs and cheap motels and repurposed as a material for Pinteresque word play and witty Wittgensteinian investigations of language. Jenny Holzer is being invented. So is Tracey Emin.

His sculpture is similarly impactful. In 1968 he buried a tape recorder in a block of concrete. All that’s left of its former identity is an electric cord hanging uselessly out of the back. Every piece of conceptual art made since then has searched for this same interplay between the visible and the implied. As for the concrete cast he made in 1968 of the empty space under his chair — you could not ask for a more exact precursor of Rachel Whiteread.

His video work is just as pioneering. The way he uses the monitor itself as a black box in which the action is trapped is especially telling. Inside these black cages, ghostly presences from other realities enact strange rituals and edgy actions. In Clown Torture a mad clown rants on about “Pete and Repeat, sitting on a fence”, the same complaint, over and over again. Today, we all know that clowns are creepy and should never be allowed near children, but in 1987 it was a recent insight.

Although some of the video pieces have lengthy running times, none of them needs to be sat through for long before their point is made. They’re excellently compact and immediately prickly. What a shame that so few of Nauman’s copyists have continued his precision and have preferred instead to bore us with hour after hour of video windbagging.

A set of contorted faces in which the artist pokes and pulls his mouth into uncomfortable distortions was echoed recently by Steve McQueen in his Tate show, especially in the film in which McQueen pushes his finger into Charlotte Rampling’s eye. But where McQueen always feels like a film-maker being arty, Nauman always feels like an artist using film. It’s a clear and important difference.

Thus the journey at every step emphasises what a transformative presence he has been. How many disciples he has. How none of them is as good as he. Everything he makes has a dryness to it, a lack of softness or romance, which I suppose is down to the maths and the physics.

He likes Beckett as well as Wittgenstein, hence the crazy conversations. There’s humour in his work, but it’s always nervy and problematic, never open-hearted or fun.

In the show’s final work, a room-size collage of flickering projections called Falls, Pratfalls and Sleights of Hand, various types of children’s entertainment have been slowed down to funereal pace and mined for their creepiness. A hand twists out a balloon dog, like the ones Jeff Koons makes, except this one is tortured into existence. A guy slips on a banana skin and falls arse over tit in slow motion, as if Ibsen had written a script for Buster Keaton.

It’s discombobulating and bleak. As I said, I came out feeling as if Nauman’s art was a perfect fit for the Covid world. On the terrace outside the Tate, a busker was playing Elton John. “If I was a sculptor, but then again no./ Or a man who makes potions in a travellin’ show…” Even that felt edgy.

Existential psycho-minimalism with serial-killer moods?

Bruce Nauman, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Feb 21