Some shows open quietly. But not the Artemisia Gentileschi show that has finally arrived at the National Gallery. Artemisia opens with a bang.

As you come through the towering double doors to the basement galleries of the Sainsbury Wing, you are immediately confronted by a blast of nervy nudity. A beautiful girl is sitting by a pool, naked, except for a slither of useless cloth draped across her thigh. Above her, two looming baroque blokes lean over a parapet and invade her space in a particularly aggressive manner. They’re so close they can blow in her ear.

Fear snaps on to her face. Her hands go up protectively. To make it all worse, a miraculous gap in the clouds has allowed a shaft of unswerving light to pick her out and emphasise her naked vulnerability. It’s disturbing. Such a forceful piece of storytelling.

Unbelievably, Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1656) painted that picture when she was 16. Her name and the date, 1610, are inscribed illusionistically in the stonework, as if some ancient cutter of inscriptions had foreseen her prodigious presence. The subject is, of course, Susanna and the Elders, that horrible biblical record of creepy bloke behaviour where the “fair Hebrew wife” Susanna is leched over by a pair of village elders, who spy on her as she bathes and demand sex from her. Artemisia’s near-contemporary Shakespeare alludes to these infamous biblical circumstances in The Merchant of Venice. Apparently, he named his daughter Susanna after this same heroine. But I digress …

The point we should be focusing on here is that painting this powerful and disturbing picture at the age of 16 is beyond any usual measure of artistic talent. This is an exceptionally rare display of prodigy. And before this review slips into the inevitable stuff about her rape, her feminine scream and all that, the right and fair thing to do is to recognise her sensational talent. Artemisia Gentileschi was better, earlier, than pretty much any artist who ever lived.

She was also spookily prescient. In 1617, a year or so after painting Susanna and the Elders, she was raped in the studio by a baroque jizzpin called Agostino Tassi, a fellow painter and friend of her father. The subsequent trial was recorded in a court manuscript that is the second exhibit here. It details how they tortured her with ropes to make sure she was telling the truth. How bravely and brazenly she toughed them out. How witty she was in her ripostes.

Just two exhibits down and, frankly, I already felt concussed. “Wow, wow, wow,” went the noises in my head. I knew her story — who doesn’t these days? — but the evidence of her prodigy was startling, as was the fierceness of her femininity. To top it all she was snappy, witty, funny.

The show ahead is a detailed account of her career, arranged in chronological clumps. Occasionally it skips sideways for a thematic detour, but mostly it starts at the beginning and ends at the end. Also in the opening room is a superb Judith and Her Maidservant by Orazio Gentileschi, Artemisia’s father and teacher.

Orazio was the best of Caravaggio’s disciples: the one who expanded Caravaggio’s revolutionary lessons most effectively. All the things that Caravaggio did — targeting you with a sense of reality, making everything feel intimate and close, setting his art at night, using violence to gain your attention — were passed on to Artemisia.

Including Orazio in the opening room, however, makes something else immediately clear. Superior painter though he was, he never brought the fierce sense of personal involvement to his art that his daughter did. Artemisia’s output feels connected umbilically to her story. A naked Cleopatra, the reclining Egyptian queen poisoning herself with a snake, completes the opening room. It was painted when Artemisia was 17. And what you see straight away in the nudity is insider knowledge. The angle of the breasts, the plumpness of the tummy — this is the handiwork of someone who knows. This is female nudity as a description of the facts, rather than a projection of desires.

Artemisia’s personal involvement is her most revolutionary aspect. Caravaggio had done it too — she must often have met him and talked to him — but never with this same aura of universal meaning. For the first time in western art the feminine voice is intervening proactively, making itself unmistakably evident. The result is an immediate enrichment of art.

The next few rooms are relentlessly exciting. Artemisia’s most famous image, the gore-fest in which Judith is shown decapitating Holofernes, is represented by two versions. In the earlier one there’s lots of blood leaking from Holofernes’s neck. In the second it spurts out in torrents, like a baroque fountain. An enthusiastic revenge has become a wallowing in the blood.

For me, Artemisia’s sense of personal involvement finds its most prescient form in a gripping row of self-portraits in which she presents herself as a female martyr: Saint Catherine, who was tortured beneath a spiked wheel; Saint Cecilia, who was struck thrice with a sword, but continued singing and became the patron saint of music. In the Saint Catherine she fixes us with a look of haunting resignation as she touches the wheel. With Saint Cecilia, she strums absentmindedly on a lute and pins us to the wall with an accusatory stare. Brilliant.

Nervously, timidly, I would like to suggest here that Artemisia’s taste for dressing up and her fierce preoccupation with her own identity can be recognised as distinctly feminine characteristics: that this is the first example of something that would later cascade out in the art of Cindy Sherman, Frida Kahlo, Tracey Emin. Yes, baroque men dressed up as well and painted plenty of self-portraits, but never with this same bellicose air of spoiling for a fight. Artemisia’s scream — “Here I am!” — bursts into art like water from a cracked dam. There. I’ve said it. Now where’s a sofa I can hide behind?

At intervals the show detours into smaller investigations. I particularly enjoyed intimate handwritten letters sent by Artemisia to her lover, Francesco Maria Maringhi, for whom she eventually dropped her hapless husband. Don’t masturbate, she instructs Francesco, when you see a picture of me. Wait for the real thing.

Back on the exhibition’s main track, she pops up briefly as a jobbing portraitist, too briefly to prompt any firm conclusions. Except, perhaps, that she’s always at her best when the story she appears to be telling is her own.

From 1612-20 she’s in Florence painting her goriest killings, including the savage beheadings of Holofernes. From 1620-27 she’s in Rome, a gentler painter, who returns, in 1622, to the subject of Susanna and the Elders with a touch that has grown more exquisite and an atmosphere that feels less hostile.

A couple of dreamy Mary Magdalenes take the show into a new realm of nocturnal thoughtfulness. When she returns, finally, to the story of Judith and Holofernes, it is not the beheading she paints, but a delicate moment of candlelit hesitation when Judith and her maidservant, having murdered their oppressor, think they hear someone approaching and fumble nervously in the shadows. What a great painting.

There’s a strong sense here of her constantly evolving, changing styles and moods. In 1630 she moves to Naples and the large slab of career that follows is devoted to a bigger and less distinctive art. She remains inventive in her storytelling, and the women she paints are always worth focusing on for their pinpoint characterisation (her skill at painting clothes never lets up; it’s one of the show’s revelations), but when other hands join in to add the landscapes and the architecture, this communal approach, typical of Naples, has the obvious effect of blurring her presence.

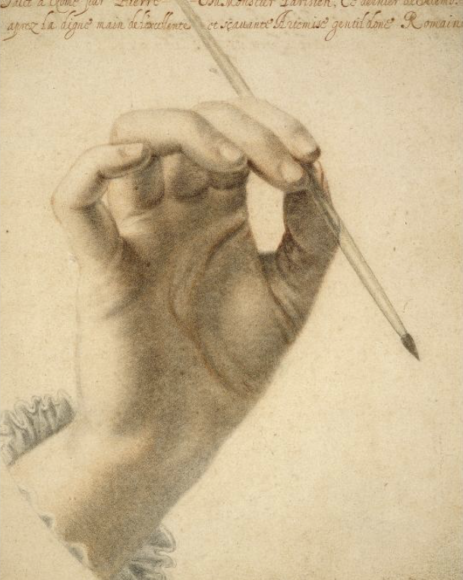

In 1638 she voyages briefly to England, and works for Charles I, alongside her father, Orazio, who’s already here. The English interlude is shuffled around to make it the show’s conclusion. It’s in England that the last of her great paintings is done: that stretching, twisting, single figure from the Royal Collection in which Artemisia presents herself symbolically as the embodiment of Art.

It wasn’t really the end. She went back to Naples and had another 20 years to go. In truth they were 20 years of jobbing work and decline, and I don’t blame this impeccably constructed Artemisia fest for fast- forwarding through them.

Artemisia, National Gallery, London WC2, until Jan 24