Bridget Riley is full of surprises. One of those surprises is that she is full of surprises. Nah, you may be thinking, never. Especially if you’re from sarf London, as she is. Norwood. Born 1931. Next stop Croydon.

But wherever you’re from, sudden changes of direction and happy explosions of enthusiasm are not what you expect from one of the art world’s most austere and cerebral presences. “Use the grey matter, Bridget,” her mother used to instruct her. And she famously has done. Loads of it.

Bridget Riley doesn’t do interviews. Yet here she is talking to me. Bridget Riley is cold and reserved. Yet here she is giggling merrily at her own aperçus. Bridget Riley lives a monastic life. Yet that is surely her perched on the waterside at St Katharine Docks with a bottle of beer in one hand and a fag in the other. Glug, glug. Puff, puff. It’s in a film from 1968, true, but it definitely is the queen of op art.

She’s agreed to give a rare interview because the biggest show of her life opens this week in London, at the Hayward Gallery. It’s the biggest not only in numbers — with work from all the phases of her mammoth 70-year career — but also in heft and import. When you get to 88, you are no longer in the business of needing progress reports or display opportunities. When your age gets Titianesque, you are after summaries, optimum framings, big stampings on the national consciousness.

To find her is a pleasant bus journey through Notting Hill, to an elegant Regency crescent of stuccoed houses in the Nash style. Exactly what you’d expect from the doyenne of calm, clear, rational abstraction: an art as crisp as a folded napkin at a Fortnum’s tea. But wait. Where’s the house number? Ah, there it is. Two bits of masking tape, stuck loosely onto the glass. DIY numbering of striking insouciance.

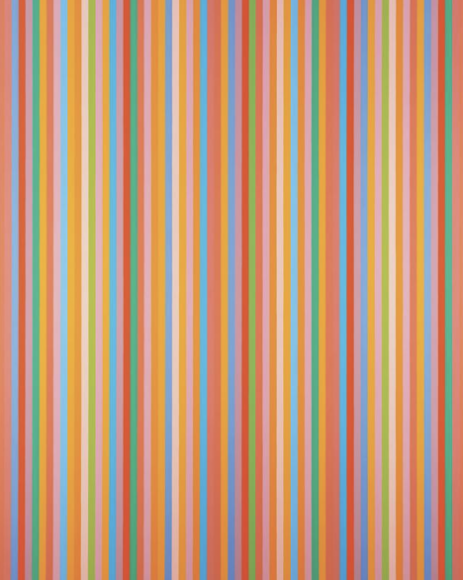

I’m met by Alexandra, one of Bridget’s neat assistants, who ushers me into a dazzlingly white front room hung mostly with stripes and squiggles of mid-period Riley. The floors have been painted white as well, to maximise the light. And the in situ pictures, with their zigzags of brightness, evoke a tangible sense of nature, like shafts of light falling between the trees. On one wall, a huge framed poster of a Cézanne show held at the Grand Palais in Paris in 1995 features a close-up of a Cézanne pine, with stripes of the vibrating landscape of Provence glimpsed between its branches. If you redrew it with a ruler, you’d get a Riley. Speaking of which, where is the master?

In the loo, it turns out. It’s the last door on the left before the kitchen, and I’m heading there myself, having opened the broom cupboard by mistake, when out steps the merry house-owner, giggling to herself. Bonjour Madame Riley.

She’s giggling about something I wrote in a recent review of a show at the Wellcome Trust. “Ha-ha,” she twinkles, her cheeky little face lifted into a smiley badge of wrinkly amusement. “Thank you for teaching me what ‘woke’ actually means.” Well I never. Perhaps Alexandra slipped her the cuttings before I arrived.

I’d been hard on the Wellcome. I’d fisted into a pretentious display called Being Human, which I accused of not being about humanity at all. They should have called it Being Woke, I blared, of a show full of jukeboxes playing plague music and wonkily crafted video attacks on the American hamburger. “Ha-ha.” She’d had some sort of run-in with the wokists of the Wellcome herself, and was delighted someone was calling them out.

Back in the white room, we settle ourselves around a perfectly circular table across which she scatters the installation plans for her Hayward show. Her team is in there now, working out how to fit her huge career into the beautifully brutalist hangars of London’s cathedral of concrete. She’ll be going there herself when we finish, to check on the progress of three new wall paintings she’s making for the show. The rest of the works will be grouped in chronological clusters, and these chronological clusters come in handy now as an aide-mémoire.

When the war broke out, her father, a printer, was called up into the army. So his wife and their two daughters, Bridget and Sally, relocated to the safety of Padstow in Cornwall, where an aunt who had studied at Goldsmiths’ College introduced her impressionable nieces to the temptations of art. Bridget still keeps a studio there, and some of the light she paints is Cornish light.

After the war, she was sent to Cheltenham Ladies’ College, the posh Gloucestershire boarding school that has more recently given us Tamara Beckwith, Nicola Horlick and Amber Rudd. The Tatler Schools Guide for 2018 notes that “confident, resilient, clever girls flourish” there, and Riley was surely all those things.

The film I found of her on YouTube, smoking, drinking, dangling her legs, also features snippets of a revealing interview about her art in which she surprised me with her posh enunciation. Cripes. With that voice, she could have been a postwar BBC news reader. Like a crystal decanter worn soft with use, most of the hard edges have now been smoothed, but there’s enough establishment authority left in her vowels to leave me hoping I never get on her wrong side.

“I think it’s been a lot maligned,” she resists, when I throw Cheltenham Ladies’ College at her. “In every single department they actually had some phenomenal teaching.” In particular, the head of painting, Colin Hayes, was helpful. The first exhibition he took his Cheltenham girls to was a Van Gogh selection. “The perfect first show.” Later, he became a senior tutor at the Royal College of Art. And she, once again, became his pupil.

Before that, in 1949, she managed somehow to get into Goldsmiths’ College. It was unexpected, because the national preference in the postwar years was “quite rightly” to give priority to those who had served in the forces. So the competition was fierce, and her portfolio was thin, though it did contain a Cheltenham copy of Van Eyck’s famous Man in a Red Turban from the National Gallery, with which she immediately proved that she had “facility”. Indeed, so much “facility” did she have that much of her subsequent career has consisted of trying not to show it. As we shall see.

At Goldsmiths she was taught drawing by the exacting Sam Rabin. At the mention of Rabin’s name, my ears prick up. As it happens, I know a bit about him and his ridiculous history. As a sculptor, Rabin’s best-known work is the art deco embodiment of the West Wind carved into the walls of the London Underground headquarters in Victoria. Jacob Epstein was responsible for the embodiments of Day and Night, while the paedophile and bestialist Eric Gill did other winds. Back in the 1990s, I used to pass beneath them on my way to work at Channel 4, and always looked up.

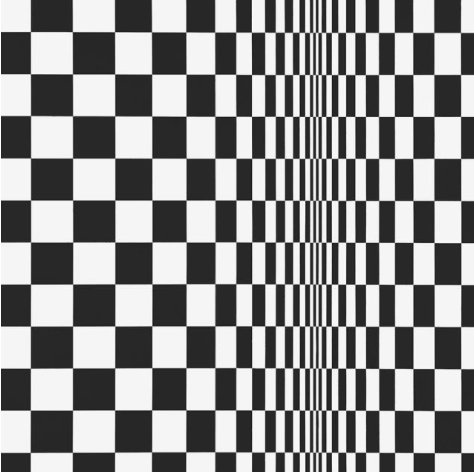

In 1928, Rabin, who wrestled in his spare time, won a bronze medal for Britain at the Amsterdam Olympics! In the 1930s, he gave up art and became a professional wrestler, fighting under the name of Rabin the Cat, and then as Sam Radnor, the Hebrew Jew. In 1934, Alexander Korda cast him as Daniel Mendoza, the Jewish prizefighter, in The Scarlet Pimpernel. So his life was as chequered as an early Riley. And he didn’t go back to art until after the war, when he started teaching at Goldsmiths.

What was he like? Demanding, smiles his most famous pupil fondly. Actually, she might possibly be his second most famous pupil, as Mary Quant was also taught by him at the time. Riley knew her a bit, but not well. And no, they never became collaborators. The fact that Quant used striking op art designs on her pioneering minidresses that were instantly reminiscent of the Riley look was only because it was “in the air”.

Now, I happen to know that having her “look” borrowed by 1960s fashion designers, especially in America, was a source of profound concern for Riley at the time. She complained that her art had been “vulgarised in the rag trade”, and that it would take 20 years for anyone to take it seriously again. But on this occasion the anger stays silent. She’s older, gentler, at ease with her grey matter and no longer feels the need, I sense, to fight the old fights.

Back in the life class at Goldsmiths, Sam Rabin, “the forgotten genius of wrestling”, would watch like a hawk while the students completed their poses. Only then would he step in and correct “what your drawing lacked or needed”. But the best thing he did was to arrange special viewings for his pupils at the British Museum, where Riley found herself holding up and examining work by Rembrandt, Durer, Michelangelo. “To be that close to something …”

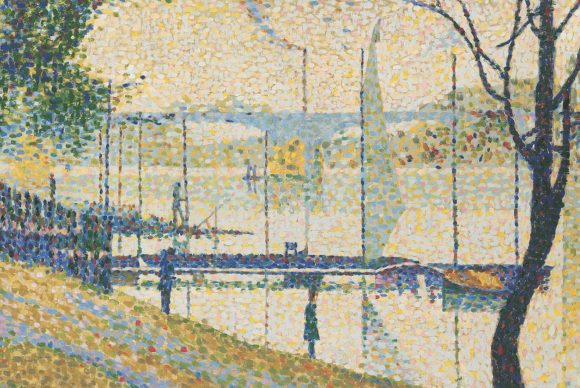

It was also Rabin who introduced her to the Conté crayon, a synthetic mix of graphite and wax that doesn’t easily smudge, with which she began producing moody tone drawings, nocturnes in grey and black, influenced mightily by her art hero, the post-impressionist Georges Seurat. Seurat is celebrated for his invention of pointillism and his pioneering use of the dot. He would later become a key inspiration for her painting. The scientific exactitude of her op art can be traced directly to Seurat’s adventures in colour theory.

Yet he started out in black-and-white as a master of the Conté crayon. And there’s nothing remotely stern or scientific about those early drawings, full of half-lights and suggestive shadows. Their ambition — the only clear thing about them! — was to create an emotional and tonal mood. And if you’ll allow me a moment of art historical wandering, we surely need to understand Riley’s op art in the same way. It looks as if it has been worked out on a graph, scientific and exact. But its ambitions are emotional and rousing. She wants to wake our eyes from their slumbers and to get them working happily. Her paintings are a splash of water in the face. She’s trying to make us see, with freshness and vividness.

I should add that everything she’s wearing today feels like a continuation of her kindly tutorial. Her outfit is a crumpled sartorial laudation to the wonders of tonality and the desire for blackness and whiteness. There’s a soft grey jacket. And a pair of trousers with a pleasantly elasticated waist, striped horizontally, soft grey, soft white. Matronly minimalism, at its most charming, modelled by the kindest wasp that ever buzzed.

When I press her on the black-and-whiteness of her early work, and her early obsession with drawing, she throws a couple of her word darts at me. What did Boudin say to the young Monet when he asked for advice? “Learn to draw. Learn to see.” It turns out she’s fond of a pointy quote, and the Boudin aperçu is followed quickly by the story of someone asking Seurat what it was he admired most in the work of great artists. “Intuition,” snapped back the king of the dot. And the gentle wrinkles on her face crease up into a Leonardo storm, and out rolls one of the gusts of hearty laughter that stud our conversation and make me want to hug her as if she were my mum and I was her boy. She’s so lovely when she teaches.

On the prickly subject of children, she’s completely unprickly, and rolls out another laugh. “It was just the way it happened. Or didn’t happen!” She’s had a couple of famous relationships: the first, in 1959, with the exotic Australian-born art tutor Maurice de Sausmarez, who took her to Italy and intoxicated her with the Renaissance and the futurists. And then with someone more suitable, and her age, the fabulous op art painter Peter Sedgley, with whom she spent most of the 1960s. That’s where it stuttered. “I didn’t envisage getting married and having children because I knew I would be a bad mother. And I had a wonderfulmother.”

Instead, she has assistants now. Lots of them, by the sound of it. They do the actual painting while she plans, designs and oversees. A few are over at the Hayward right now getting the knobbly concrete walls ready for her murals. Alexandra is here. And I think there’s someone knocking about upstairs. For the story of her assistants, she unveils what strikes me as a preternatural ability to look ahead. She’s been using them since her first show in 1962, when she got people in to do “piece work”, as it was called. “That is to say ‘per job’. Which was the old way of employing people.”

It turns out we are actually back at this business of her “facility”. She realised early on that she could do things in art. At the Hayward show, take a look at her teenage drawings and you’ll see what she means. But, as she expands later on the phone, when I call her back to get it clear, “there were plenty of people, in the past, who had ‘facility’. But who remained not very good. They didn’t have the right kind of ambition. And I actively wanted to avoid that. I gave up painting because I could. And I had to find out what I could not do. So it was quite a conscious decision.” When she finished at Goldsmiths, Rabin told her “he could teach me no more in drawing. [He said] ‘Now you have to show what kind of artist you are.’ ” So now she does the dreaming. And the assistants do the painting.

Goldsmiths was followed by the Royal College of Art from 1952-55. Artistically, they weren’t great times. After that, she blundered into teaching. And then into advertising when she joined J Walter Thompson in 1958 as a commercial illustrator. The advertising days were, by the sound of it, absolutely hilarious. “I had no talent whatsoever for layout and typography. But I could draw. So I was found something I could do usefully.”

What they discovered was that Riley could produce convincing forecasts of what the advertising projects would finally look like. “Some calculated to be rejected. Which, I only found later, I was really good at.” She remembers a tea campaign rejected because the tea packet didn’t look how a tea packet should look. “It’s woke, actually. An expected form.” Hmm. I’m not sure if her woke definition and mine are exactly in line.

The white house we are sitting in was left to her by her parents. “It’s been very kind to me.” It isn’t just her home but also her studio, where, from the top floor, she can see the sun setting. Plus it’s the headquarters of the Bridget Riley Art Foundation, a charitable organisation she established in 2011. The foundation sends young artists to Italy. It gives money to galleries. And brings out books about her work, decorated tastefully with Bridget Riley covers.

We’re back, it turns out, at the preternatural planning of which she is so surprisingly guilty. The urge to leave a legacy dates back to at least 1962, when she had her first show of op art dazzlers at the Victor Musgrave Gallery. People imagined that, because she was starting out, the young achievements would soon be forgotten. “You’re so wrong. That’s the last thing I want to do,” she thought.

So yes, she’s cocky. Perhaps it’s a class thing, something she owes to Cheltenham Ladies’ College. But it’s an arrogance that has achieved excellently tangible things. Near the top of my list would be the role she played in 1968 in setting up the Space studios in St Katharine Docks. It’s a story told in wobbly art vision in the YouTube film of her guzzling beer and puffing at fags.

Finding a derelict warehouse by the river, Sedgley persuaded the GLC to rent it to a battalion of artists to use as studios. Having previously worked in cramped bedsits, they abruptly found themselves in a huge acreage at a prime riverside location. Riley loved working there. When the lease ran out, the search began for similar spaces, and a global sequence of urban development was accidentally invented. Artists find a derelict space. They do it up. They get kicked out. The yuppies move in. Et voilà, Shoreditch.

So that’s bad. But Space is still at it, still finding studios for artists in the impossible squeeze of urban London, and as my wife was in one of them when I met her, I can only thank Peter and Bridget for my own artistic happiness. Later, in the 1980s, Riley became a trustee of the National Gallery, and when Margaret Thatcher tried to ensure that the adjacent land was used for commercial development, she was one of the band who saw her off, and who ensured the building of the Sainsbury Wing instead.

So I start thanking her for that, too, but she interrupts to tell me that it wasn’t Thatcher who was the chief danger for the National Gallery. There was someone far worse than her. “Heseltine,” she spits, with toxic Cheltenham venom. As I said, remind me never to get on her bad side.

Bridget Riley, Hayward, London SE1, from Wednesday