Ah, the memories. The rooms in which Painting Now is on show at Tate Britain are the same rooms in which I once found myself on the telly with Tracey Emin, attempting to discuss the future of painting. Was it “dead” or not? That was in 1997. As you probably remember, Emin got immoderately drunk that night and stormed out of the discussion, informing us shoutily that she would rather talk to her mother. The rest of us carried on with our weighty circumlocutions, and more or less agreed that painting would never die because the urge to produce it was too primary. Nowadays, however, it is one way of making art, not the only way.

Those remain my views. I therefore approached Painting Now with a spring in my step at the prospect of seeing some energetic new contributions from the painting corner of British art. Five painters who were doing fresh things, I assumed, had been brought together in a show that would provide a sense of catch-up with recent developments in painting, I further assumed. Silly me. I had forgotten that this is the Penelope Curtis era at Tate Britain, and that in the Penelope Curtis era, anything straightforward can be made confusing.

Since Curtis took over as Tate Britain’s director in 2010, the gallery has displayed a remarkable ability to ruin good ideas with muddle-headed implementation. Painting Now is a classic example. Instead of a catch-up with recent developments in painting in Britain — which would have been useful — we get an unlucky dip of five painters with nothing in common, who find themselves involved in a display so vague and bloodless, so dull and overcurated, it shocked me with its lassitude. Having trouble sleeping? Go and see Painting Now.

When I say overcurated, I mean overcurated. The five painters have been chosen by no less than three curators (1.666 artists each?), whose ramblings in the catalogue are a disgrace to the English language and an insult to the few poor souls wandering through Tate Britain on the day I visited. No wonder there was hardly anyone there. Why should anyone visit an institution so insensitive to the needs of communication that its catalogues contain sentences that proceed “As painting is no longer in a position of autonomy — alone and apart — this also entails a move away from an idea of medium specificity, defining a practice as ‘painting’ or ‘film’, and towards a post-medium age, what a recent conference at Harvard examined as the ‘medium under the condition of its de-specification’ ”?

You don’t have to attend a post-medium conference on de-specification at Harvard to recognise that here are three curators writing imbecilically for other curators, not for the visiting public. Making everything worse is the fact that the unfortunate artists exposed to all the David Brent-style thinking that has taken over art are by no means negligible presences. Not all of them, at least.

Tomma Abts won the Turner prize in 2006 and is a painter of considerable delicacy and presence. Her compact abstractions are unusually small — about the size of a head and shoulders by Holbein — and this evocative Old Master scale adds something classy to their atmosphere. And because every Abts image is different — some stripy, some blobby; some lurid, some monochrome — each picture here has a tangible sense of event to it, as if every delicate configuration of stripes and shadows was a once-in-a-moment coming together. Lovely.

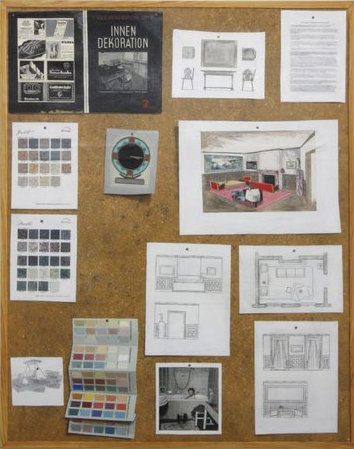

Also impressive, again, is the fascinating Lucy McKenzie, last seen stealing the show in A Bigger Splash at Tate Modern. It’s going to take me another 20 or so exhibitions before I fully understand what McKenzie is up to with her weird mix of architecture and pornography, but whatever it is involves an excellent range of illusionistic skills. Here she presents a set of perfectly realised trompe l’oeil paintings of a set of notice boards on which various architectural drawings and photos have been pinned. They are completely convincing, right down to the drawing pins holding the scraps of paper in place. On the other side of the room, these same mimicking skills have been used to transform the dust jacket of Fifty Shades of Grey into a Miss Marple mystery set in Belgium.

McKenzie, it turns out, used to pose for porn photographs herself in her student days, and the show’s most startling work is another fully convincing illusionistic notice board featuring a letter from her to some gallery curators refusing permission for a selection of those porn pics to be shown in an exhibition. The perfectly painted letter on the perfectly painted notice board has been given the title Self-Portrait. One of this event’s more legible ambitions is to show contemporary painting behaving like conceptual art. McKenzie’s work is the clearest example.

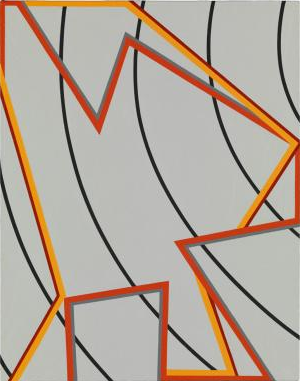

This, then, is a collection of painters who paint for the wrong reasons: not because they feel the joy or exhilaration of paint, but because using it is a means to an end. There are lots of things wrong with the dank curator culture that has taken over contemporary art, but the single worst thing is the lack of excitement it encourages. The drab threesome who complete the cast list of Painting Now bring the sorts of moods to this show that belong in a sociology class. Simon Ling paints grubby East End shop fronts observed at wonky angles. Gillian Carnegie paints black cats going up black staircases. Catherine Story paints brown totems that are apparently based on the shape of old movie cameras. It’s as if the artist’s palette has had all the colours removed except browns and blacks.