The lovely history of Chinese painting that the Victoria & Albert Museum has organised for us has a gigantic timeline: 700-1900. That is such a lot of cultural history to squeeze into one display. Over at the Royal Academy, the awful Australia show has taken a pasting for trying to condense a mere 250 years of Australian art into a single event. And that was Australian art: shrill, provincial, unbacked by tradition. Yet here we have one of the world’s most sophisticated artistic societies, a society with two millennia of unbroken creative achievement behind it, seeking to encapsulate 1,200 years of painting in a single journey. It ought to be impossible. But it isn’t. Why?

Because the great creative tradition celebrated here is one that nurtures continuity. If you put together a timeline of what was happening in western art in this same period, 700-1900, starting with, say, the Vikings, then progressing through medieval illumination, gothic, Renaissance, the baroque, the rococo, neoclassicism, Romanticism, academic art, impressionism, symbolism, expressionism — you would find yourself jumping crazily hither and thither like, yes, a Chinese firecracker. From the Vikings to Edvard Munch in one thrust: that would be silly. But this journey isn’t.

Some of the sense of frictionless progress that characterises this event is deceptive. My untrained eye, untuned to subtle Chinese differences, would have missed more than it noted. (On which point, Chinese authorities, when are you going to unban me from visiting China? I feel no need to apologise for the film I made in 2003 describing the protests against the system mounted by Chinese contemporary art — but that was 10 years ago. Surely my penance is served? I want to know more about ancient Chinese art. Let me in!)

Witness the case of the Four Wangs, a group of 17th-century artists whose achievements are highlighted midway through the exhibition. Also known as “the Orthodox school”, the Four Wangs sought specifically to continue the achievements of the generation that preceded them. Which is why one of them, Wang Jian, created an extraordinary set of landscape scrolls in which he deliberately mimicked the different styles of painting employed by 12 of his greatest predecessors.

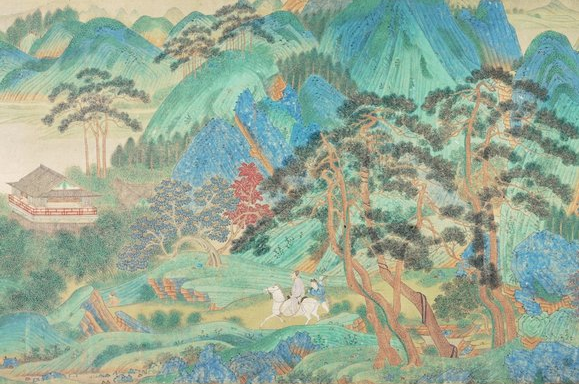

It’s a remarkable work. Imagine someone taking Rembrandt, Rubens, Caravaggio, Velazquez, Poussin, and deliberately copying their style in a single sequence of pictures. In western art, the result would be a mess. Nothing would go with anything else. In Chinese art, in Wang Jian’s amazing Landscapes in the Manner of Old Masters (1669-73), I struggled to spot the differences. All are landscapes. All are vertical. All feature swirling mountains at the centre and swirling rivers at the base. All twist upwards knottily like a gnarled old tree. I do not doubt the differences are there. My point is that difference in Chinese art is of a different order from difference in western art.

Chinese art values continuity, tradition, repetition. Which is why this show remains calm and consistently lovely as it traces a full millennium of intensely complex cultural history, while the Australia show falls apart grotesquely. (Now will you let me back in, Chinese authorities? All I was trying to do in my film was defend your glorious native tradition against the destructive attacks of the Olympic bulldozers. If you let me back in, I too may fully appreciate the creative viewpoint of the Four Wangs. And that’s good, no?)

The show’s masterstroke is to begin with an exquisite 12th-century handscroll showing ladies of the court preparing newly woven silk for painting. This gorgeously coloured image breaks the display’s chronology and upsets the moody conservational twilight in which it is set, but it allows the V&A to add an immediate explanation, in an adjacent video, of how Chinese paintings were actually made. The process of painting on silk is thoroughly different from painting on canvas. The helpful explanation adds immensely to the pleasures ahead.

Chinese paintings were usually presented on scrolls, and always read from right to left. In most instances, they would spend much of their history rolled up, and were brought out only on specific occasions. Which is why the pastel shades of the silk-making scene remain so fresh. And why so many pictures here have a teaching quality: a sense of pent-up enlightenment. Whereas western pictures would just hang there all the time and do their thing, Chinese art had to wait until it was unrolled to share its message.

Apparently, most of the finest examples of Chinese painting that survive are here. They have been divided into big chronological slabs, beginning with the dense religious iconography of the Buddhist phase; progressing through the tussle to misty, lofty, meaningful, mountain landscapes in the Ming years; and ending with lively street scenes and portraits influenced by western art.

Many of the painters were also poets, whose verses and pictures were presented together. The resulting dual-prong imagery isn’t interested only in describing things. It seeks also to jump into your thoughts and prompt cosmic questions. So we’re watching the invention of conceptual art. And that’s not all. In one of the show’s least expected paintings, a group of ladies from the court is shown hitting a small ball into a hole with the help of a long stick with a flat blade at the end. In the next picture, the ladies pass a bigger ball to each other with their feet, and keep it in the air with a confident display of keepy-uppy. Both images date from the second half of the 15th century. Thus, it wasn’t just conceptual art that was invented by the Chinese. They also invented golf and football.

Elsewhere at the V&A, anyone walking past the front of the building recently may have noticed an estate agent’s sign seemingly offering a flat for sale inside the museum. Alas, there isn’t one. The sign, and the flat, are fictitious. Both have been created by the cheeky conceptual duo Elmgreen & Dragset.

Mind you, the fictitious flat, located upstairs at the V&A in a posh suite of rooms, doesn’t feel fictitious. On the contrary, it feels scarily real as it sets about dumping you in the life of an ageing English architect whose career is over, whose dreams have been broken, whose aesthetics are out of date and who can no longer afford to live here, hence the sale. Every detail of his fictitious life has been carefully implied with props and artworks, in one of those all-enveloping installations that seeks to transport you to somewhere else.

It’s brilliantly done. And its final ambition — to question the values of the modern world without seeming to question the values of the modern world — is a marvellously sneaky artistic strategy. The only issue is the status of the fictitious neo-Georgian settees created for the flat by George Smith. They’re too perfect. I want one.