When I was a teenager — jejune, pretentious, cocky — I wrote a poem about the impact on me of Tintoretto. I’d been to Venice and seen his thunderous masterpieces in the Scuola Grande di San Rocco. For a few days it short-circuited my reason. Hence the poem.

In almost any circumstance, I would be too embarrassed to share it with you. It’s a daft thing. But the Chantal Joffe exhibition at the Victoria Miro Gallery dances so fiercely with the lessons of Tintoretto and is so fascinating in its complications I feel compelled to share the opening lines. Forgive me.

What I owe to Tintoretto

Is a moment deep and savage

I approached him as a virgin

When I left him

I was ravished.

You don’t need to giggle and point. I was young and reeling. Tintoretto does that to you. And in a far more adult and nuanced manner it’s what he appears to have done to Chantal Joffe.

The backcloth to her new collection is a period of doubt that followed a big show that she had in Paris. It prompted the question: where now? In the search for answers, she went to Venice and encountered Tintoretto. She was already a fabulously fluent painter, and at 56 was way past the virgin stage, but she found herself battling with his thunderous example.

The first thing to notice about the dozen paintings that make up her riveting new chapter is their size. Like Tintoretto she’s mostly painting wall-sized whoppers. The second thing to notice is the involvement of more figures than before.

Joffe is chiefly known for her single figure investigations, ordinary faces pulled out of the crowd, like the charming cast of urban types who decorate the platform walls of the Elizabeth Line at Whitechapel station. That’s her typical work. Yet here she deals recurringly with bigger groups and more complex compositions.

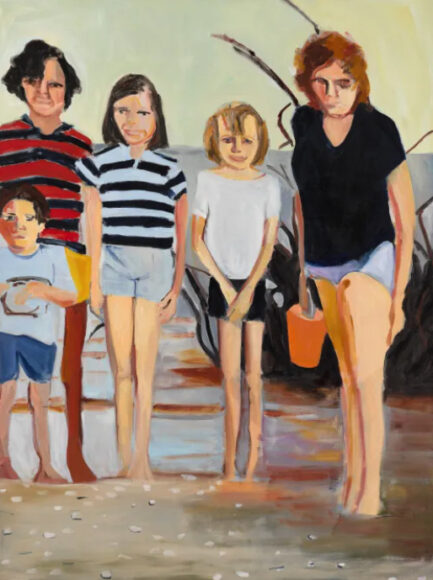

Significantly, all the paintings refer to her past, to a peripatetic childhood with Mum and Dad, two sisters and a brother. When they are all in the picture together they form a scrum. Nothing like the teeming hordes of Tintoretto, but busier than usual.

The shift in mood that accompanies this shift in subject is telling. Tintoretto always feels as if he is painting emotional states rather than tangible realities. And Joffe’s journey into the past takes her away from the everyday. Where previously her portrayals felt emotionally placid — sweetly fond in the main — something bigger and sadder is at work here.

You feel it most directly in a looming image of her dad cradling one of the family babies. Where Tintoretto might give us a mother and child, she gives us a dad and child. The emotional intensity of these family memories is nothing like the water cannon of thunderous feeling you get with Tintoretto, but it does feel less diluted, more imaginative.

In Tutu she shows herself on stage with her sisters: three little girls soaking up the applause in pretty white costumes covered in stars. But when you zoom in on their interaction, subtle twists in their expressions signal a competitive wickedness.

These more complex moods are accompanied by a formal inventiveness that also feels new. It’s the source of the show’s victories and also its occasional awkwardness. Arranging four, five, six figures into ambitious compositions is four, five, six times more difficult than dealing with singles. Here and there it results in too many sardines in the same tin.

But the desire to aim higher leads also to exciting successes. In Matrushka Dolls Joffe and her sisters are dressed up as traditional Russian dolls in costumes made by her mother. One looks right, one looks left, one stares straight ahead as their individual identities battle with the decorative repetition of their costumes. Look what painterly fun Joffe is having with the abstracted Russian folk designs.

Her touch has grown freer and braver. She’s less concerned with prose and keener on poetry, notably in Bananafish, a gorgeous beach scene where five members of the family have water lapping around their ankles in a spectral light that’s throwing stars on the water.

In the show’s newest image, a portrait of her mother leaning against a bright green staircase, the lessons learnt elsewhere have enriched the single figure. The mother is delicately thoughtful, but the star of the painting is the spectacular green staircase described with juicy painterly enthusiasm. All over the show the waters of Venice seem to be adding liquid to the mix.

At the National Gallery, Joseph Wright of Derby (1734-97) is being bigged up in a display that focuses on his “candlelight” paintings. The most famous of these, the immensely popular An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump, shows a scientific experiment being mounted in the kind of dramatic nocturnal lighting you might usually expect in a religious scene, especially a Nativity.

Invented by Caravaggio as a way of yanking the audience more forcefully into the action, these candlelight effects — or “tenebrism” as art historians call it — is presented here as part of the Enlightenment’s search for deeper truths. But the cloying children’s faces gathered in the dark, the recurring full moons, the effortfully conspiratorial set-ups, the occasional lurches into wonky anatomy, seem to me to have more in common with John Lewis Christmas ads than with the investigation of reality.

What we have here is a showbiz ambition to put bums on seats.

Chantal Joffe: I Remember, at the Victoria Miro Gallery, until Jan 17;Wright of Derby: From the Shadows, at the National Gallery, until May 10