Lisa Brice is no spring chicken. She’s 56. Yet only in the past few years has she managed to transform herself from “promising female painter with complex ideas about the role of women in art” to “ubiquitous art star”. These days you need a few million in the bank to buy a hefty Brice.

What’s commendable, though, is that the process of adding all those noughts to her prices has not involved a drop in radical intensity or any kind of softening. Big changes have occurred in her style — we’ll come to a whopper in a moment — but they do not make her work easier to fathom.

Born in South Africa in 1968, Brice has had a peripatetic career that has involved alighting in places as unexpected as Trinidad, before eventually making London her home. This richness of origins, the fact that she is anything but a home counties girl who went to Goldsmiths, has endowed her art with a quality we might happily describe as “unusualness”.

In particular, there has been her curious focus on the colour blue. The women in her pictures have been blue. The backgrounds have been blue. Blue has been her dominant colour. According to her origin myth, oft repeated, this trademark blue was inspired by the Blue Devils she saw in Trinidad at the carnival — demonic carnival characters, painted blue, who date their beginnings to the resistance to slavery; the celebrated Jab Molassie. By painting her women blue, Brice was associating them with a resistance to another form of oppression: masculine oppression.

That is also the background to her interest in art history. The subservient role played by women in art, as models, muses, lovers, in the work of Manet, Caravaggio, Degas, gets her goat. In a Brice picture, the models fight back and reclaim the canvas. Manet’s women kick Manet out of the studio and throw a party. Caravaggio’s Judith teaches the female cast how to decapitate a bloke.

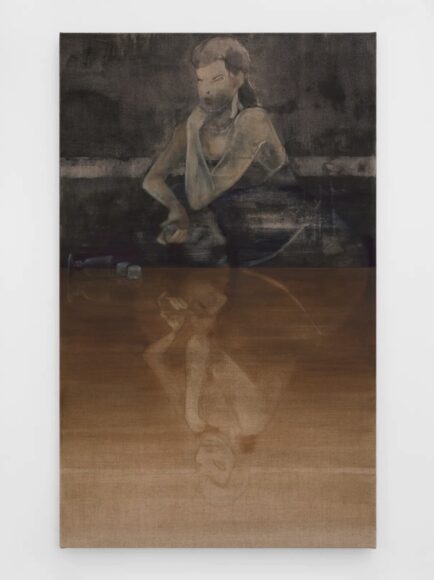

Until now, all this has been happening in azure hues: a women’s revolt in subversive Trinidadian willow pattern. But her new show at the new Sadie Coles gallery in Savile Row — a fresh-on-fresh experience — has her swapping colours and switching abruptly to brown. It’s an unexpected move and caught me by surprise. What’s also surprising is how the switch has deepened her work: enlarged it, made it less shrill.

The latest incarnation of the Sadie Coles gallery is housed in what used to be the Burlington Fine Arts Club, a cigar-smelling gentlemen’s retreat for the big beasts of Victorian artistic machismo — Ruskin, Whistler, Rossetti. Taking it over and handing it to Brice is, therefore, a double act of female reclamation.

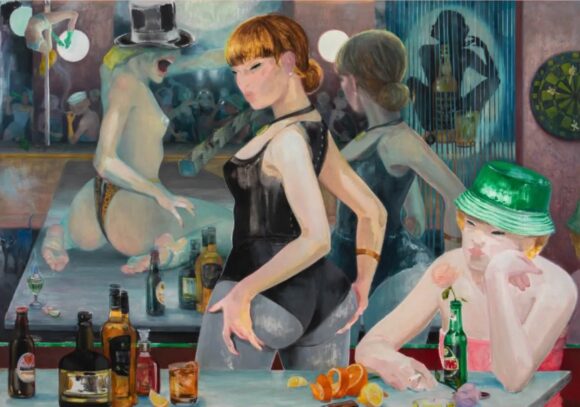

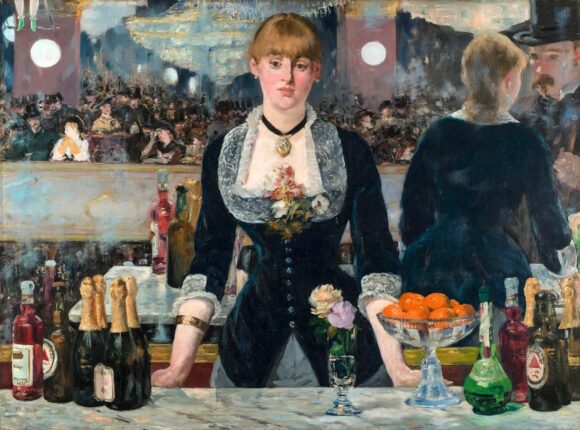

In her surprising brown suite Brice continues her tussle with Manet and especially, I suggest, with his Courtauld masterpiece A Bar at the Folies-Bergère. It’s the painting in which a forlorn barmaid stands behind a bar filled with bottles and is approached by a sinister bourgeois in a top hat whose reflection we see in a giant mirror at the back.

The Folies Bergère was a notorious pick-up joint where women were treated as commodities to be hired. It was something Manet also wanted us to notice. But in a series of clever riffs on the Manet set-up, Brice turns the woman-bar-mirror triangulation on its head and recasts the females as sassy barroom Amazons who have repurposed the beer bottles as Molotov cocktails and smashed the bottle necks to create jagged glass weapons. If the dirty-minded bourgeois approached Brice’s new cast of barmaids at the Folies Bergère he would have been decapitated and his head held up in a sack. Run, Top Hat, run.

In the blue colour of old, all this would have felt more illustrative — blue is close enough to black to produce insistent outlines. But the new brown softens the shrillness and allows moods of greater sensitivity to emerge. The way Brice has painted the beige reflections in the shiny bar shows off a deep painterly skill. The gentler harmonies of the browns make her work feel more poetic. She isn’t just attacking the old masters, she’s enjoying them — and learning from them.

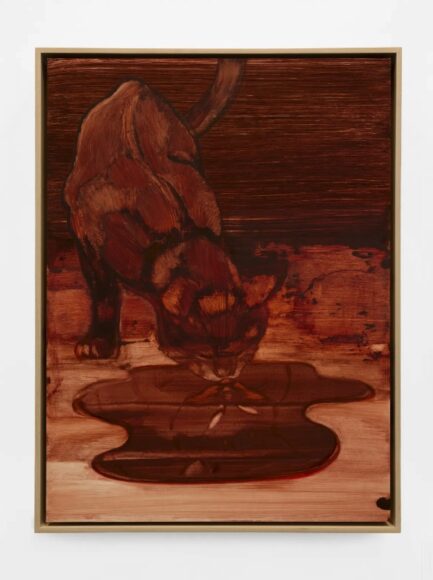

In another of the show’s rooms we find ourselves in a boxing gym where, once again, the female cast is having fun: smoking, drinking, admiring itself in the gym mirrors. Turfing out the men from their own turf, the sisters are doing it for themselves. And prowling about their feet is their spirit animal, the hissing cat, borrowed from Manet again, from the black cat that exudes such demonic intensity as it stares at us from the end of the bed in Manet’s infamous depiction of the prostitute Olympia.

It’s an exciting new show in an exciting new venue. Bravo Lisa Brice. Bravo Sadie Coles.

Bravo also to the Frieze art fair, which turned out to be surprisingly fresh and stimulating last week. Perhaps the chatter about the art world being in decline prompted contemporary galleries to try harder? Something was certainly buzzing.

The prevailing uber-theme that painting is once again dominant will surprise no one. It’s been heading that way for a decade. In the entire fair I only counted one video work. Here, however, is my bullet list of the five key lesser themes:

• Abstraction is back.

• Mystical hocus-pocus is big.

• Embroidery and wall hangings are surging.

• Nudes painted by women are everywhere.

• Postcolonial attitudes are powering on.

Lisa Brice, at Sadie Coles HQ, London W1, until December 20