However many times the Turner prize gets stamped on, however fiercely we wish to dispose of it, however bad it gets, it survives the hammering and comes back for more. It is the cockroach of art and its resilience over four testing decades is almost heroic.

This year’s effort has travelled to Bradford, Britain’s City of Culture for 2025. The gods of art clearly approve of the choice because on the day I visited Cartwright Hall, the impressive Victorian pile hewn out of honey-coloured Yorkshire stone in which this year’s award has fetched up, there wasn’t a cloud in the heavens. Blue sky above, Cartwright Hall glowing yellow below, it was like an accidental recreation of the Ukrainian flag: immediately rousing. That was on the outside. Inside, the Turner prize was up to its usual cultural nonsenses.

Of the shortlisted artists, two are worthy of the attention. The other two, alas, feel like makeweights who raise the usual doubts about the Turner’s purpose. Are we really here to choose the best artist or to be morally improved by a travelling evening class of right-on social politics?

When I walked into Nnena Kalu’s sprawling mix of lumpy sculpture, fashioned from brightly coloured gaffer tape and discarded bubble wrap, my immediate reaction was: what a mess. It was up there with the worst art I have seen at the Turner.

The drawings on the walls, relentless and repetitive spirals of circling colours, were marginally better: the wooden panelling at Cartwright Hall was able to do some heavy lifting. It did not stop the display as a whole looking talent-free and chaotic.

Then I read the accompanying wall text. And discovered that Kalu is autistic; that art is a glorious release and therapy for her. Suddenly, my harsh critical response was transformed into an act of cruelty.

I left the room wondering who was right: the art critic judging the evidence? Or the Turner judges showing compassion and widening the definition of good art? Over to you.

Unfortunately, Rene Matic, in the second of the poor displays, suffers from comparable stumbles. In the film that accompanies her contribution she comes across as troubled and elfin. Mixed race, she complains continuously of feeling culturally divided. On her back she has tattooed the declaration “Born British Die British”. So — another artistic narcissist obsessed with identity issues.

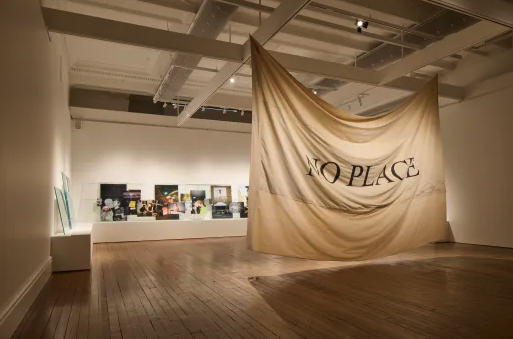

In the centre of her room, a giant flag says “No Place” on one side and “For Violence” on the other. Nice slogan, zero artistic effort. The most ambitious contribution is a line of wonky photos of pro-Palestinian demonstrations, gay marches and “Free All Antifas” graffiti presented dully behind panes of glass.

The problem here is not the causes she is espousing. The problem is the absence of any transformative ambition that might turn the good causes into good art. It’s the recurring problem with art driven by identity politics.

Fortunately, there is still half the shortlist to come and here at last we find some worthy contributions. Zadie Xa is from Vancouver, but lives in London. She is of Korean origin and her art flits between her assorted backgrounds while also adding big dollops of sci-fi, a spiritual fascination with marine life and a spectral interest in other universes.

As cocktails go, it could hardly be richer. Yet out of these crazily diverse ingredients she has fashioned an installation that is fabulous and fabulously coherent, a psychedelic other world that is as beautiful as it is wacky.

To enter, you take off your shoes and step onto a shiny gold floor that makes everything in the room look infinite and spacy. From some suspended sea shells we hear mysterious whispers: the twittering of dolphins or the haptics of an iPhone? On the walls, colourful paintings made with ancient Korean techniques take us on a swirly journey that could be into outer space, but could also be underwater.

The skill and care that has gone into creating every inch of this hugely ambitious installation saves it from any accusations of kitschness. It’s magical and brilliantly achieved. And someone needs to take Matic by the ear and drag her into here to see how art can earn our respect if it puts in the necessary effort.

I’ve saved the best till last. Mohammed Sami was born in Iraq and the world he grew up in — wartorn, dangerous, fragmented, despotic — has baked profundity into his art. His paintings, originally shown in Blenheim Palace where their troubled moods clashed with the luxury of the English stately home, are displayed here on pure white walls, a simple framing that ups their intensity.

All his images imply dark goings-on, but don’t actually describe them. A shadow cast on a round desk surrounded by plush chairs could be the shadow of a ceiling fan, but it could also be an approaching helicopter, come to bomb. A field of sunflowers seems to have been trampled by a line of horses. A covert cavalry operation? A mass grave? We never find out. But neither do we stop imagining the worst.

Every painting gives us just enough information to trigger some serious fretting. And because of what is happening in Gaza and Ukraine, a pungent aroma of global pertinence seems to leak from the art. If the Turner prize jury has any sense it has to go for Sami. Alas, the Turner prize jury rarely displays sense.

Turner prize 2025, at Cartwright Hall, Bradford, until Feb 22