In art some questions are difficult to answer. Was it really Leonardo da Vinci who painted the Salvator Mundi that was sold to a Saudi prince in 2017 for $450.3 million? We’ll never know for sure. What was Marcel Duchamp really trying to say when he turned a urinal upside down and called it Fountain? Beats me. Art is full of mysteries and some of them are unsolvable. But if we ask who was the most influential collector of modern times the answer is obvious. It was Charles Saatchi.

Not even Saatchi’s fiercest haters, and there are a lot of them, can argue with the assertion that he transformed the art world. In collecting, there was a way of doing it before him, and another way after him. As the man who bankrolled the YBAs and unleashed them on global art, his presence in aesthetics was just as cathartic.

Anyone doubting these claims, or too young to remember, should allow their imagination to join me on the banks of the Thames in London, on the St Paul’s side of the river, where we can look across together at Tate Modern, the bricky behemoth that is now the world’s leading museum of contemporary art. Without Saatchi it would not be there. Trust me on that. Trust me as well when I add that what he achieved requires a complex remembrance.

The memories are prompted by a show that has arrived at another towering London museum that owes its existence to Saatchi, now 82. Located in a Georgian palace off the Kings Road, the Saatchi Gallery in Chelsea used to be the home of the Territorial Army. Today its displays attract up to a million visitors a year, although most factions of the British art world avoid it like the Black Death.

The new show there, billed as “Saatchi Gallery at 40”, fills most of the building and consists of work by a smattering of the artists Saatchi has unleashed or supported in the four decades of maverick warfare he has waged on the British art establishment.

A helpful timeline guides us through the main battles and begins with the opening of the original Saatchi Gallery in a disused paint factory in north London in 1985. In 1985 art galleries were not usually encountered in disused paint factories. They were housed in purpose-built, neo-Greek Parthenons on Millbank, like what is now Tate Britain, or in the posh National Gallery in Trafalgar Square. Not in 30,000 sq ft of looming industrial whiteness located miles from the centre of town in a no man’s land without Tube stations.

Saatchi, however, had been to New York and seen what could be done with dead industrial spaces when they fell into the hands of creative minds. Inspired by the loft dwellers of Manhattan, he began mounting a series of rousing, inspirational, exciting art shows that seemed suddenly to have rammed their finger on a cultural pulse that was crazily throbbing.

It began with startling selections of American minimalism — Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre. Andy Warhol popped up in a wow of a display. Soon we were catching up with developments in post-pop New York, with Jeff Koons and Robert Gober. The painterly frenzy christened A New Spirit in Painting gave us Kiefer, Polke, Baselitz. Then, to top it all, Saatchi unleashed the YBAs. In the course of a few, short, stabby years, the British art world had been shocked into transformation.

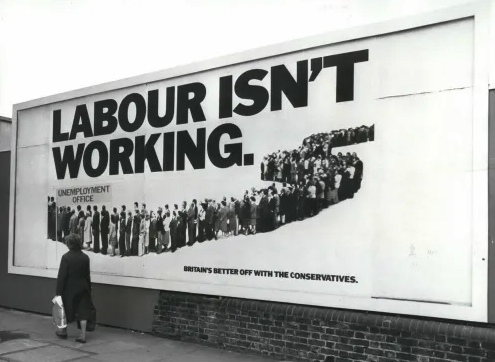

Unfortunately, not everyone was keen on these electrifying displays. While his gallery was altering the art world’s DNA, Saatchi, in his other guise, as co-founder of Saatchi & Saatchi, the advertising kingpins who had ensured the political triumph of Margaret Thatcher, was managing to make himself the most hated figure in cultural Britain. His sin was to be a scheming arriviste with loadsamoney from the shallow world of posters and plugola.

When Saatchi launched the YBAs he took a mallet to the foundations on which the British art world was built. To do that he needed to be arrogant, uppity, pushy and excessively competitive. And boy, was he well stocked with all those flaws. He once took me on one of the Saturday drives around the galleries on which he found the young artists he supported. It involved hiring a black cab for the day and popping into shows armed with a plastic bag crammed with private view invitations.

In most cases the visits lasted a few minutes. If he didn’t immediately like what he saw, out we rushed. No performance or film or video. It was always painting, photography and sculpture. On my day with him he didn’t buy an entire show for peanuts. On other days he did. People hated him for it.

It’s easy to dismiss these methods as superficial. That’s what the art world thought at the time. Its gatekeepers loathed his quick, ad man pace. What they didn’t realise, because unlike him they didn’t actually go to all the rackety shows opening up in deserted corner shops and East London cellars, was that art too was changing. The Hirsts, the Chapmans, the Emins were operating on a timescale that was faster and poppier. Saatchi’s ad man instincts weren’t forcing his tastes on to the art world. His tastes were coinciding with fresh developments.

But the barrow boy methods were jarring. And much else about him boiled the blood. His cultivation of a mysterious image, never turning up at his own private views, never giving interviews, angered the roundheads who wanted to give him a public drenching. When he married Nigella Lawson, the daughter of Thatcher’s cruellest chancellor, and not yet the national treasure she has since become, he might as well have been Lord Voldemort shacking up with Cersei Lannister.

My wife and I were invited once to dinner at their new flat in Eaton Square. As well as his glittering collection of Georgian silver, Saatchi had installed Tracey Emin’s notorious My Bed, a messy hit at the Turner prize, in the art-packed apartment. Since we were dining with Charles and Nigella, we were expecting the haughtiest haute cuisine. Instead Nigella got in some sausages from Marks & Sparks.

His finest year was probably 1997, when the big YBA exhibition, Sensation, opened at the Royal Academy and became an international hit. Everywhere it went, it triggered exciting rethinks. The noises grew so loud, even the British art establishment could hear them. And whispers began to circulate about an ambitious new home for contemporary art that was going to be opened in a converted power station on the banks of the Thames, opposite St Paul’s Cathedral. Three years later it happened.

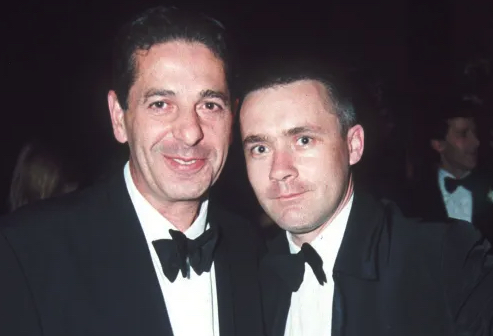

Prompted by the Saatchi Gallery’s ramble down memory lane, I fired off a missive to Saatchi Yates, the trendy Mayfair gallery run by his only child, Phoebe, and her husband, Arthur, in the not-at-all-hopeful hope that he might have forgotten the awful things I had written about him in the past and that we might meet again to rake through the ashes. To my astonishment he agreed. And that’s how we ended up in his favourite restaurant gossiping over the halibut like the two old boys on the balcony in The Muppet Show. It was off the record, but fascinating.

He looks snazzy. A touch more stooped than before, perhaps, with hair that had been allowed to grey and grow longer in the Don Johnson fashion, but just as talkative, smart, catty and lethal as ever. By the second glass of red wine the years had flown by and we were beginning to get honest with each other.

Closing the original gallery in the converted paint factory in what he calls “Kilburn”, but the rest of us call “St John’s Wood”, was, he admits, the biggest mistake of his art world life. Searching for the reason why he left the centre of so much evident art action he stabs out a single word: “Hubris.” Just a few hundred people a week were making their way to “Kilburn”, and he wanted more.

In 2003 the Saatchi Gallery moved to County Hall, on the South Bank, which had been vacated by the Greater London Council. At County Hall, the claustrophobic oak interiors had a mournful effect on any art that was shown in them. The artists hated it. So did I. So did everyone. Except him. He liked the challenge.

I remember bumping into him at the Frieze art fair after I had given one of his County Hall shows a savage review and the forlorn look on his face as he approached was new. “If I don’t have my eye, I have nothing,” he said, scowling sadly. I thought he might break into tears. He was always more fragile than most of us suspected.

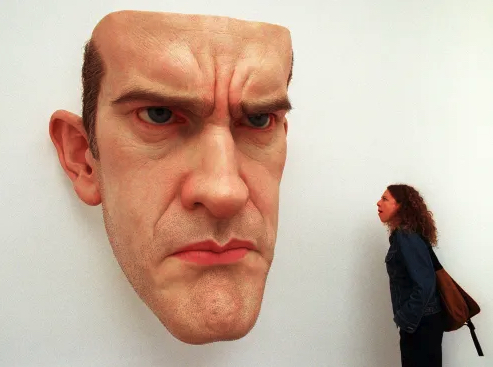

But he was also impertinent, arrogant, shifty and driven by the raging fires of the outsider. When the pioneering Sensation show was being organised, the gang of Goldsmith’s artists whom it chiefly featured were vehemently against the inclusion in the YBA ranks of two of Saatchi’s discoveries: the painter Jenny Saville and the spooky sculptor Ron Mueck. Saatchi forced them both in. They were among the event’s stars.

The Tate supremo Nick Serota collared him once to ask why Saatchi had managed to discover all these new British artists while his own curators had not. Having been on that art-hunting trip with him, and having encountered zero curators on the way, I, too, can answer that one: because they didn’t put in the miles. Because he worked the weekends, and they didn’t.

Having moved the gallery to the columned palace in Chelsea, determined to keep the entrance to it free (Why? “Ethos,” he snaps back), he found the outgoings too onerous and offered the building and 150 prize works from his collection to the Arts Council. It turned the offer down. So he gave the treasure instead to Great Ormond Street Hospital, which had saved his daughter’s life when she was two by diagnosing her with glandular fever.

He’s achieved so much, why he has never been ennobled? He was offered a title in 1996, at the same time as his brother, he says with a sigh. But unlike Maurice, who is heavily gonged and sits in the House of Lords, he’s against them. They’re a sign of vanity. I presume Sir Nicholas Serota, Sir Norman Rosenthal, Dame Tracey Emin and Sir Antony Gormley disagree.

The Long Now: Saatchi Gallery at 40 is at the Saatchi Gallery, London, to Mar 1