The first thing to say about Lee Miller at Tate Britain is that it is a marvellous exhibition, full of riveting photography and powerful moments. The second thing to say about it is that it is dense with sexual complications and psychological darknesses that are more problematic than the show wants to admit. It’s not a cover-up. But it is a sanitised version.

Miller was born Elizabeth Miller in Poughkeepsie, New York, in 1907. The “Lee” bit came later. Her father, Theodore, was a successful engineer who taught his daughter the rudiments of photography while also recording her in erotic nudes until she was in her twenties. When she was seven she was raped by a family friend, who gave her gonorrhoea. I mention it here because the show does not and seems keen to keep things polite.

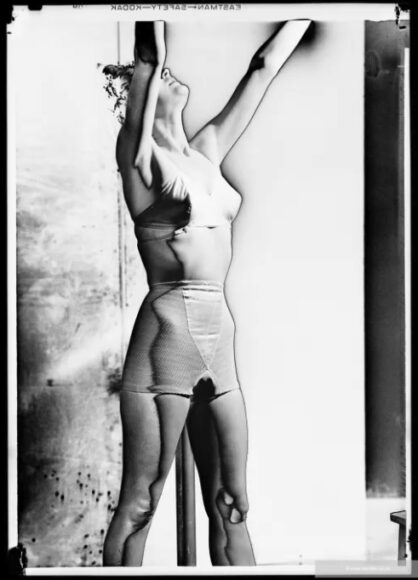

We first encounter her when she’s 19 and already a successful New York supermodel, popping up in prestigious fashion spreads. Blessed with spectacular beauty — think of the young Cameron Diaz — as well as being tall, clever and never afraid to take her kit off, she charmed her way instantly into the studios of New York’s best photographers. It appears to have been the Vogue photographer Edward Steichen who first encouraged her to swap sides on the camera. When it came to older men, she knew from the start how to press their buzzers.

In 1929 she left for Paris, where she apprenticed herself to Man Ray, the celebrated surrealist who had been born Emmanuel Radnitzky but who changed his name for the same kinds of reasons she had. Ray was almost twice her age, but she quickly became his pupil, muse, collaborator and lover — not necessarily in that order.

The work they made jointly is moody and surrealistically typical — unexpected juxtapositions, looming shadows, dramatic close-ups. Together they invented the celebrated technique of solarisation — for which Ray is usually given solo credit — which fills photographs with halos of magical light.

They also made kinky films. Thus we see Ray in a woman’s nightie affecting a phoney femininity while flashing his schlong at us. Miller, meanwhile, removes the plastic from a priapic Brancusi sculpture as if she were sliding a condom off.

Unusually for a Tate show, the display refrains from making prickly comments about the power dynamics in the Ray/Miller relationship. So let me be the one who admits to some unease here, notably when we reach the photographic triptych in which Miller is made to wear a dog collar while being yanked around by a moustachioed Man Ray lookalike.

When we move away from the shadowy interpersonal work with Ray there’s an immediate drop in intensity. Her solo attempts at surrealist photography are decent rather than brilliant. She crops inventively, searches for the unexpected, favours extreme close-ups, but lacks the instinctive visual cannibalism that distinguishes the truly great surrealist photographers.

What she has got is a societal fearlessness that is her privileged American birthright. We see it expressed most weirdly in a close-up of a woman’s severed breast. A cancer sufferer has had a mastectomy. Miller puts aside all notions of decorum and shows the bloody breast served up on a plate like a snack in a bistro.

The second of her older men is the wealthy Egyptian businessman Aziz Eloui Bey, whom she tempts away from his wife and marries in 1934. Nearly two decades older than her, Bey allows her to turn photography into an occasional hobby and travel round the Orient recording sandy ruins and spooky rock formations. Again, she’s good at this rather than dazzling, although some images do cut through, notably the triangular shadow of the Great Pyramid at Giza falling doomily over Cairo.

By 1937 Egyptian life has begun to bore her and she moves back to Paris and starts an affair with Roland Penrose, a surrealist painter, pioneering curator and, naturally, older man, though this time by only seven years. They move to Hampstead in London just in time to witness the opening bombardment of the Second World War.

At this point the show shifts suddenly into another, higher gear. Surrounded by the tangible darkness of war, Miller finds a cause that seems genuinely hers rather than inherited from earlier surrealists. Her war photography is immediately more potent than the pictorial games that preceded it. The broken statues she finds in the ruins of London have a horror to them that does not need topping up with wacky invention.

This knockout sense of the truth being darker and more surreal than anything invented by surrealism reaches its apogee when she becomes an official war photographer and tours the battlefields of Europe recording the evidence. In her most famous photograph she shows herself taking a bath in Hitler’s Munich bathtub on the day he commits suicide. It’s such an extraordinary act of reclamation, surreal and psychologically twisty.

But the show’s most devastating room, a room that moved me to tears, has her visiting the concentration camps of Dachau and Buchenwald, where the bodies are piled up on rubbish tips and dead German soldiers float in the mud like old tyres on a Hackney canal. The greatest thing Miller did was to refuse to avert her eyes from these terrifying sights and to record them for us as unshiftable reminders of what humanity is capable of when it allows hatred and prejudice to flourish.

It’s not a lesson confined to this show. Many of the shadows she records can be seen again today, darkening our horizon.

Lee Miller is at Tate Britain, London, until Feb 15