There’s a lot of art about “the theatre”, but most of it is not about the theatre as you or I know it. It’s not about the tremendous dithering of David Tennant in Hamlet or Mark Rylance’s comic malignancy as Johnny in Jez Butterworth’s Jerusalem. Great artists are pathologically immune to the great performances of others. They go to the theatre to shine the spotlight on themselves.

When Degas went to the theatre it was to point out how strikingly the stage lights silhouetted the orchestra or to ogle the nimble flicker of the prepubescent ballerinas making their Paris debut. For Hogarth, the theatre was a doll’s house in which he could re-stage the foibles of his age. Sickert went to the music hall to record the squalor of its baying working-class audience.

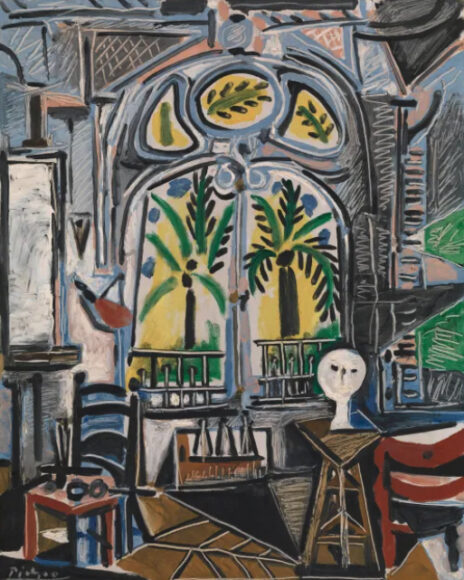

This difference between what the theatrical experience means to us and what it means to art is made particularly vivid by Theatre Picasso, a riveting display at Tate Modern. Picasso was drawn to the theatre for various reasons: for its sexual possibilities (his first wife was a Russian ballerina) and for its fashionable elegance and international glamour. The theatre pandered to his weaknesses. What it did not do was suit his deep, fiery, surreal and highly personal creativity.

Thus the wonky stage designs he produced for Sergei Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes constitute the weakest moments of his brilliant career. And the first thing to say about Theatre Picasso is that it avoids all that comprehensively. No recreations of the costumes for Parade. Or that bloody backdrop for Le Train Bleu, again. Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes have been redacted from this event, allowing it to take us on a much more interesting journey.

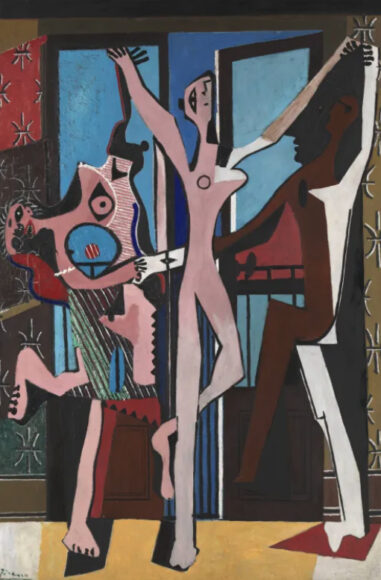

The centrepiece here — or more accurately, the destination — is The Three Dancers, the edgy bit of stagey surrealism, painted in 1925, that many would argue is the most important painting in the Tate collection. The fact that it is 100 years old gives the gallery the kind of excuse it needs these days to put on a Picasso show. In today’s art history, he’s generally the coconut and angry damsels throw the balls.

So what Tate Modern has done, in a nimble bit of curation, is hand over the event to the trans performer Wu Tsang and the “intersectional” writer Enrique Fuenteblanca. Between them they have imagined a completely new journey on which to take Picasso’s theatrical art.

What that journey is is impossible to define. It’s too chaotic and accidental to arrive at clarity. The absence of the Ballets Russes moment is like the removal of a motorway sign. But because of the directional chaos there’s a freshness here, a jumpy energy, which suits Picasso and makes his art feel alive.

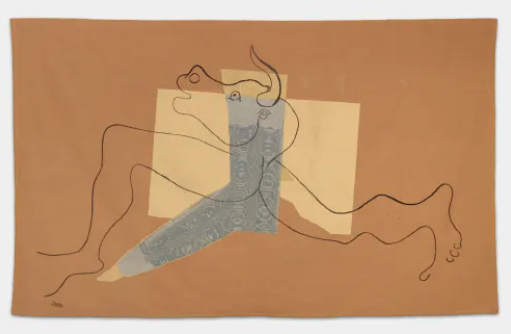

The focus, I think, is intended to be Picasso’s love of “performance”, both his own taste for dressing up and his appreciation of other people’s role-playing. Tsang and Fuenteblanca obviously have a personal stake in performance as a life strategy. But we’re not talking Tennant’s Hamlet here. The kinds of performers Picasso was drawn to were flamenco dancers and bull fighters, spangled heroes from the lower rungs of Spanish culture.

The show begins with a flickering film of Picasso pretending to be Carmen tugging clunkily on a cigarette. He obviously loved dressing up, although the humour it was done with strikes me as a very different thrust to the crushingly serious identity issues that drive, for example, Tsang.

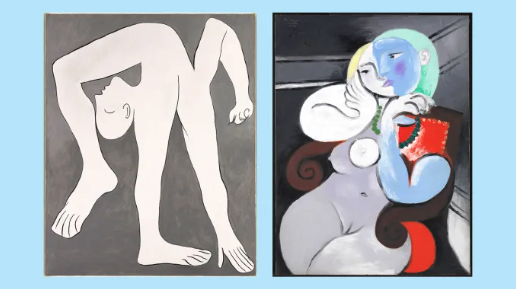

The opening section focuses on Picasso and “obscenity”, which is to say his erotic art, notably the Vollard Suite with its snorting minotaur crashing through the lives of a sprawling harem of displaying nudes. Most recent Picasso displays would have cancelled this rampant misogyny.

Picasso and his muses get a section. Weeping Woman pops up. There are occasional appearances of his sculpture. And it doesn’t take long to realise that what’s really happening here is that Tate Modern is showing us every Picasso it owns and that the “theatre” angle is an excellent excuse to display them.

The result is a show that feels adventurous and fresh. Reconsidered by Tsang and Fuenteblanca, his art springs to life. And to top it all, in the show’s climax, we get The Three Dancers displayed on a pretend stage, lifted up in lights for us to examine properly and dramatically.

The “dancers” are two women and a man, their figures twisted spikily into an edgy tango. The woman on the left is grimacing grotesquely. The man on the right is silhouetted mysteriously. The dancing nude at their centre seems to be the focus of their tension.

We’re watching a tug of love. I was reminded immediately of Princess Diana’s lament about three in a marriage being a bit crowded. Picasso has cast the central figure in the Camilla Parker Bowles role.

The man is clearly Picasso, reduced, typically, to a silhouette. The screaming woman on the left is, surely, his Russian wife Olga, whom he had begun to caricature nastily in his art. The dancing nude is a lover who has come between them.

The Tate has other theories and we’ll never know for sure. But what’s excellent here is how excitingly the show has framed the possibilities.

It’s been a long time — several years — since an event as stimulating as this opened at Tate Modern. If it were up to me I would leave these rooms exactly as they are for ever, as a thrilling tribute to Picasso.

★★★★★

Theatre Picasso is at Tate Modern, London, to Apr 12