A good thing to do when a new pope is elected is to visit the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome and see what they have done with Michelangelo’s Risen Christ. I haven’t been myself yet. It’s too early in the reign of Leo XIV to be certain where he stands on art. But I will make the pilgrimage, and when I do I will search out Michelangelo’s statue on the left of the altar and stare at its groin. It’s the acid test.

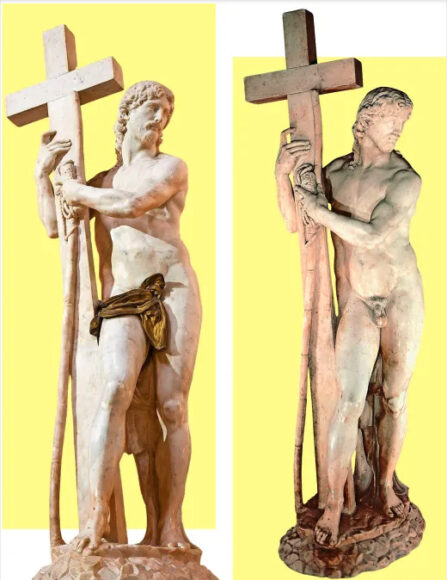

The Risen Christ is considered to be one of Michelangelo’s weakest works. Finished in 1521, its final touches were entrusted to a pupil and the general complaint is that it was overpolished and standardised: that it lacks the terribilità for which Michelangelo was renowned.

It’s true. There’s a blandness to it. Compared with his best work it lacks balls. But only metaphorically. In real life balls are something it can boast. Indeed, the balls of the Risen Christ are exactly what we need to search out when we go to Rome. Are they on show or not?

What Michelangelo has depicted here is Christ after his resurrection, carrying the cross on which he was executed. After three days of death he has returned to earth in divine glory. And saved us. It’s the Easter moment. But there’s a complication.

When Jesus was buried in the sarcophagus he was wrapped in a winding cloth, as was the custom. When he rose again the winding cloth was left behind. They found it later in the sarcophagus. So he would have been naked when he reappeared. Which is how Michelangelo chose deliberately to depict him. The risen Christ, as naked as the day he was born.

Unfortunately, not everyone saw it that way. In 1546 the church authorities got in someone to fashion a floating loincloth, made of bronze, to cover up the divine bits Michelangelo had left exposed. And this is where it gets interesting.

The first time I went to Rome was after the pontificate of John XXIII, the liberal pope. There was no loincloth. Jesus was as naked as Michelangelo wanted and as the Bible tells us. But on subsequent visits I have usually found it on. It depends on the pope.

Popes who are art-loving and open-hearted encourage us to see the statue as Michelangelo intended. And the loincloth is stored. The other kind of pope gets it out again and covers up the symbolic genitalia with which Michelangelo was seeking to emphasise that Jesus, when he came to earth, was fully human, just like the rest of us.

I remember this here because I have been making a TV series for Sky Arts about three of art’s most insistent subjects — the erotic, the horrific, the satanic — and at pretty much every step I have had to deal with impactful issues of censorship, propriety and social expectation. The art itself has been heady and exciting, some of the greatest art ever made. But the people controlling access to it have often been a nightmare. Time after time the intentions of the creator have been overruled by the whims of the gatekeeper.

Poor old Michelangelo was a regular victim of this type of control. His masterpiece in the Sistine Chapel, the swirling fresco that confronts the cardinals in their conclave when they unleash a new pope, has been the subject of various campaigns of coverage. In particular The Last Judgment on the Sistine Chapel’s altar wall, its most important ecclesiastical moment, has had terrible things done to it.

When the end comes, all of us will rise again from the dead and stand before Christ to learn our fate: up to Heaven or down to Hell? And the Bible tells us we will all be naked for the big decision. So that’s how Michelangelo painted us: as undressed when we leave as we were when we arrived. In its original form The Last Judgment was the most glorious and extensive celebration of human nudity ever painted.

But not everyone saw it that way. After Michelangelo’s death in 1564 a busy mannerist called Daniele da Volterra was called in to cover up the exposed bits on The Last Judgment with tasteful robes, swirls and wisps of cloth. Thus da Volterra earned himself the sad art historical nickname of Il Braghettone (“the breeches maker”). Most of the offending bits were hidden from sight, until subsequent restorations revealed them again. What we have before us today is partly how Michelangelo wanted it, and partly how various papacies left it.

The films I’ve made are not about censorship. But they are about fabulous moments of artistic creation that have been hidden or looked down on or ignored because they do not meet the general criteria for great art. The creators might think so, but the guardians do not.

The problem is that at some point in the story of art certain subjects, thrusts and approaches were redacted from the civilisation myth. Erotic art, for example. It has been, is and always will be one of art’s key subjects. Nothing in human history has ever been as important as having babies and ensuring the survival of the species. So art has had to play its part.

Pretty much the earliest art we know, the so-called Venus figures created by our cave-dwelling ancestors 30,000 years ago, are fertility figures. The famous Venus of Willendorf, with her pendulous breasts and prominently incised vulva, is more conspicuously naked and sexual than any of the figures in the Sistine Chapel. From the beginning art could not shy away from naked human truths. Nor did it find them offensive or shocking. Those are modern reactions.

Today, art ideas seem to have grown even more censorious. When we were filming the extraordinary erotic carvings created in Khajuraho in northern India in the 10th century, or the acrobatic sexual manoeuvres described in shunga art in Japan during the Edo period, there were all sorts of testy hoops to be jumped through to gain access and permissions. The notion seemed to hold sway that civilisation was a long trek up the hill of propriety: the kind of journey Kenneth Clark makes in his celebrated BBC series, a journey that involved ignoring huge tracts of crucial art. Art that should not be written out of the story.

Another of my topics is horror. The journey of art is packed with recurring moments of brutality and gore. That current art favourite, the baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi, produced some of the most horrific images ever painted. Her Judith cutting off the head of Holofernes, with blood spouting crazily from his severed neck like water from a Bernini fountain, is an extraordinarily violent picture.

These days it has acquired a shiny feminist gloss and is seen as Gentileschi’s psychic revenge on men in general and the artist who raped her in particular. Perhaps. What it certainly is is an image created because violence in art sells. It always has done, and always will. The same kinds of imperatives that made Sam Peckinpah’s movies so gory — gore puts bums on seats — are the imperatives that also drove Gentileschi in her darkest moments.

Although Clark avoided brutality and death in his polite tracing of civilisation’s path, art has recurringly depicted them. Indeed, one of art’s key tasks has been to imagine and give form to the dark stuff that lurks deep within us. Just because it has not been celebrated in the civilisation myth does not mean it isn’t there.

My third film is about the Devil. Or, more broadly, about the forces of evil. Every society has sensed the presence of evil. Most societies have made an effort to describe it. And the heavy lifting in that effort has been done, again, by art.

There are no illustrations of the Devil in the Bible. No biblical passage says he had horns and a tail, cloven feet or red skin. All those details had to be imagined by artists saddled with the task of inventing Satan from scratch. And what fun they’ve had doing it.

In his original form, as Lucifer, he was radiantly handsome. A beautiful fallen angel. And, of course, he hasn’t always been a he. All around the world, the king of evil has often been pictured as a queen. The fact is, as soon as you step off the overtrodden path of “civilisation” and start to explore what art has really been up to in the shadows, you end up in very exciting places.

Arts Most Erotic, Horrific, Satanic starts on Sky Arts on Sep 30 at 9pm