Art has many powers but its superpower, the one that comes closest to magic, is its ability to turn nowhere into somewhere. All over the world, in situation after situation, we have seen it happen.

Bilbao was one of the least visited cities in Spain until 1997, when the Guggenheim Museum, designed by Frank Gehry, turned it into a must-see art destination. Sleepy Arles in the south of France would be empty all year round if Van Gogh had not lived and suffered there. Even the Louvre in Paris would not be as popular if it did not possess the crowd magnet that is the Mona Lisa. Art can make people come to it in dramatic numbers.

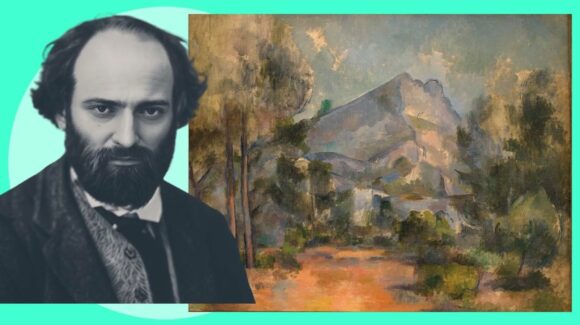

Which, I presume, is why 2025 has been deemed “Cézanne Year” by the small but ambitious Provençal city of Aix. Paul Cézanne, painter, game changer, grinch, was born here in 1839, 186 years ago, and died here in 1906, 119 years ago. Neither 186 nor 119 constitutes a meaningful anniversary. There’s no obvious reason to choose now for a celebration — except the thoroughly 2025 reason that it will bring in the crowds.

With that in mind, Aix has created an ambitious Cézanne trail that sends us through the streets and culminates in a hoard of his works at the chief museum, the Musée Granet. It all starts at Jas de Bouffan, a historic bastide on what was once the edge of the city.

Bastides are a cross between a château and a farm: posh houses surrounded by fields that in the past produced olive oil and wine. Cézanne’s father, an Aix entrepreneur who made his first fortune manufacturing hats, and his second owning a bank, bought Jas de Bouffan in 1859. It was where Cézanne developed, learnt to paint and centred his art.

The gardens are immediately familiar in their recurring combination of yellow and green. It’s unmistakably a Cézanne combination, although the local nature found it first. The most exciting stretch of the visit, however, takes you indoors. Until recently the building was a wreck and most traces of Cézanne’s story here had been lost. But in 1994 it was acquired by the city and a painfully slow restoration commenced. The results are finally on show.

Upstairs, the tiny studio his father built for him has been decked out with simple props. In his mother’s bedroom you can see the stucco relief of Leda and the Swan that later inspired a creepy response. But the location that quickens your pulse is the Grand Salon, the showy downstairs living room that the young Cézanne filled with frescoes. Between 1860 and 1870 this was his playground.

Not much of his original work remains —the subsequent owners hacked it off the walls and sold it in bits. But a clever set of projections shows us exactly what he painted and where. The first scenes were evocations of the seasons, women pretending to be spring, summer, autumn and winter, done in a faux-naive style and signed, weirdly, “Ingres”, after the great French neoclassical painter whose work is also on show at the Musée Granet. I can only imagine it was one of Cézanne’s uncomfortable jokes.

In the Grand Salon he also painted an ungainly portrait of his father reading a newspaper, now in the National Gallery in London, which was once positioned haughtily between the seasons like a depiction of Jupiter. A grateful son giving his generous father some wobbly thanks, maybe.

In truth, it all feels somewhat uncomfortable. The paintings are dark and brooding, where in other stately locations they would be light and charming. Strangely, some angsty religious scenes are added to the mix, with Christ descending into Limbo and an ugly and masculine Mary Magdalene lost in penitential prayer. The very act of filling the walls of the poshest room in the house with sprawling homemade frescoes seems awkward. With Cézanne, there’s a suspicion that you’re dealing with a painter who was mildly unhinged.

The Jas de Bouffan pilgrimage can be followed by a visit to Cézanne’s last studio, where he painted some of his finest still-lifes, and where the Mont Sainte-Victoire can be seen looming in the distance. Another exciting stop is the Bibémus quarry where he discovered some of his most cubist rock formations.

But the culmination to any visit is the show at the Musée Granet, which houses a feast of 130 paintings and watercolours. The dark images from the Grand Salon projections are replaced here by the real things: broody slabs of wall scrawling with zero ambition to be elegant. Cézanne called this first style his “manière couillarde”, which translates as his “ballsy manner”. The more you find out about him, the less cosy his thinking becomes.

All the themes he explored in the 40 years he lived at Jas are reviewed in the Granet show. His portrayals of the gardens are dreamy and calming, as if getting out of the house was a release: just him and the trees. There are many reasons why Cézanne came to be called the father of modern art but the meditative quality that makes its first appearance in the bastide gardens — where looking, painting, thinking become one and the same thing — is high on the list.

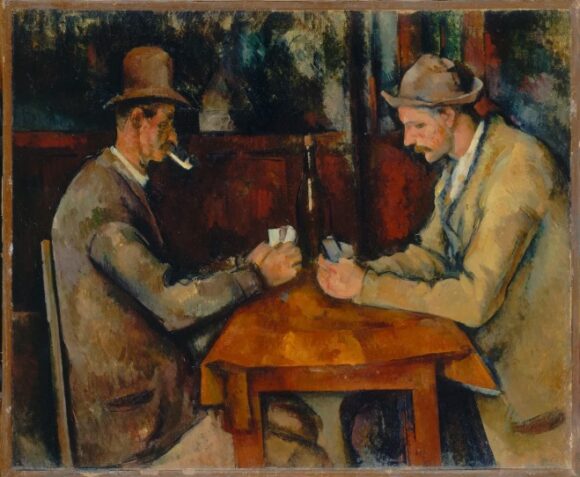

It was also at Jas that he talked the farm workers into posing as his famous card players. His first still-lifes with apples were painted there, too, and his first bathers. A simple country house on the edge of Aix-en-Provence, inhabited by generous parents and a cranky artistic genius, was changing the course of art.

Cézanne at Jas de Bouffan and the Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence, to Oct 12