Expressionism is one of the better names for an ism. It tells you what to expect with unusual clarity. Expressionist artists express deep feelings and stormy emotions. They do it with brave and direct paintwork. No overthinking. No conceptual confusion. Expressionism does what it says on the tin.

The movement’s origins lie in Van Gogh, the super-expressionist, who pioneered directness and emotion in painting. Interestingly, he was followed mainly by artists of the north — Soutine from Belarus, Kokoschka from Austria and, especially, a loud and angsty band of Germans. Something about the expressionist mode struck a resonant chord in the Teutonic psyche.

So the first thing to note about Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern’s sprawling new survey of one of the movement’s best phases, is that it isn’t very expressionist. Even the title beats about the bush. What is this show examining? Expressionism? Kandinsky? Münter? The Blue Rider? The answer turns out to be all of those things, plus lots of other stuff. If this journey sees a tangent, it heads down it.

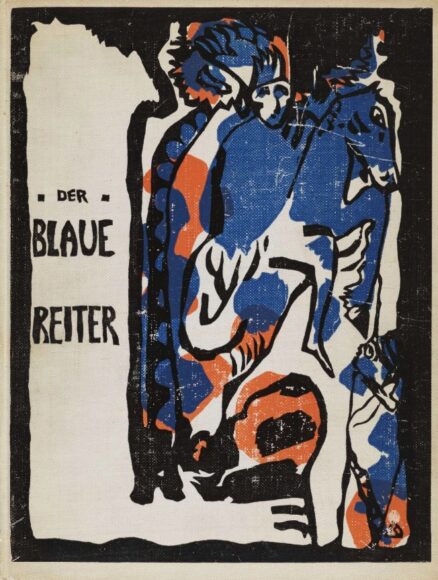

The Blue Rider was an avant-garde grouping that emerged in Munich in the 1910s and lasted until the First World War. So it was notably short-lived. The group’s name came from a painting by one of its stars, Wassily Kandinsky, although, confusingly, the artist associated most fiercely with painting blue horses was another of the Munich stars, Franz Marc. Horses in shades of cerulean were a Marc speciality. Annoyingly, no examples have been included here.

Instead we get an opening vestibule that pairs a Kandinsky painting of a Russian couple on a twilit tryst with a set of photographs of America by Gabriele Münter, Kandinsky’s partner in art and love, whose achievements the show is seeking effortfully to enlarge. When people talk of expressionism, they usually have in mind the movement’s alpha males. The new art history wants to change that and re-evaluate the contribution of the Blue Rider women.

It’s a worthy ambition. Unfortunately, no amount of huffing and puffing at Münter’s photographs of America can turn them into anything more profound than shaky amateur snapshots. Modern curatorship forgets too easily that good social history and good art are not the same thing.

As it meanders, the show is determined to expand the achievements of the Blue Rider group on as many fronts as possible. We get more of Münter’s shaky photography as she journeys to Tunisia. We get “free form” dance, a speciality of Alexander Sakharoff, who also supplies the journey with its obligatory detour into “gender flexibility”. There’s even a music space devoted to Schönberg as expressionism is pointed in so many directions we no longer see a target. Of course, what we are really watching is contemporary tastes being overlaid onto Munich’s past.

Much emphasis is placed on the women in the movement. Münter eventually emerges as a more successful painter than her photography suggests. Her portrait of Marianne von Werefkin with a golden background and a hat of many colours is a genuine expressionist highlight. Werefkin herself, alas, deserves every minute of the obscurity she has hitherto enjoyed as an artist. Bad colourist, bad draughtswoman, kitsch selector of subjects, she really is awful.

Franz Marc’s partner, who changed her name, confusingly, to Maria Franck-Marc, gives us a suite of cringy religious images that involve slamming the brakes fully on modernism, followed by thunderously sentimental paintings of children. As a baby painter, Franck-Marc cannot hold a candle to Paula Modersohn-Becker, whose marvellous contributions to a similar show held recently at the Royal Academy positioned her as an artist of exceptional significance and talent.

As the survey wanders hither and thither in its expanded picture of the Blue Rider, it becomes clear that the old story of expressionism probably got it right when it singled out Kandinsky and Marc as the ones to watch in the group. If what you want from expressionist art is thrilling colours, dramatic paintwork and explosions of invention, dwell on the Kandinskys and the Marcs.

I once went round the Palm Springs Art Museum in California listening to an audio guide by Kirk Douglas in which he solemnly informed us that Kandinsky was the painter “who took the subject matter out of art”. What he meant was that Kandinsky was the inventor of abstraction. It’s a view that no longer holds. Various female artists beat him to it by decades. But watching the tussle that takes place here between Kandinsky the nostalgic folk artist with a passion for colours, patterns and “primitivism” and Kandinsky the abstractionist-in-waiting who hides his subject is a gripping watch.

The show makes a half-hearted effort to understand the wacky “spiritual” hungers that propelled Kandinsky towards abstraction — he was yet another on/off follower of Madame Blavatsky and her influential cult of theosophy. Anyone who has tried to read his thoughts on the subject in a book called Concerning the Spiritual in Art will know already that understanding his mental processes is a feat beyond the non-divine mortal.

Another of the new art history’s signature beliefs is that the crazy religious detours of the past deserve a more serious appreciation than they have previously received. It’s part of the retreat from reason that is presently driving art. What cannot be denied is that the crazy spirituality did, indeed, prompt some great painting.

The exhibition’s central room, with a trilogy of animal pictures by Marc and some of Kandinsky’s most tumultuous abstractions, stops you in your tracks. Finally, the faffing about is over and the event delivers what all surveys of expressionism should deliver: powerful kicks of pulse-quickening art.

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and The Blue Rider, at Tate Modern until October 20