There are many reasons to enjoy — or in my case to love — Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood at the Arnolfini gallery in Bristol. The show is an in-depth examination of the relationship between mothers and their children, as seen by female artists from the 1970s to now. So it delves into the deepest human territory there is: the bearing of babies. Without which none of us would be here.

Of course, there are already plenty of mothers and children in art. The countless versions we have of the Madonna cradling Jesus might even lead us to believe the topic has been extensively tackled. It has. But only by men. The outside view is familiar. The inside view, a woman’s view, is not.

Bristol is the first stop of a touring exhibition, organised by the Hayward Gallery in London, that will also arrive in Birmingham, Sheffield and Dundee. You really should see it when it stops near you. It’s an eye-opener.

Until now, what we have mostly had in art on the subject of motherhood have been the dewy-eyed fantasies of doting artistic dads. From Perugino to Picasso, the fathers of art have gone soppy on us en masse. But their view has a narrow angle. On this evidence, and there is a lot of it, with 60 artists in the show, motherhood and childbirth have myriad moods, and none of them is as uncomplicated as a Madonna and Child by Botticelli.

To be honest — and I speak as a fully qualified doting dad — the amount of resentment, unhappiness, regret and frustration on display took me aback. There is wonder, too, and occasional flickers of joy, but they are outnumbered by the assortment of maternal sadnesses.

As it travels through Britain, the show will be reconfigured, so it is perhaps unfortunate that in its Bristol iteration it commences with a largely unhappy section entitled “MAINTENANCE”. It’s the section where women artists who have had babies remember and, in the main, lament the impact that motherhood has had on their careers.

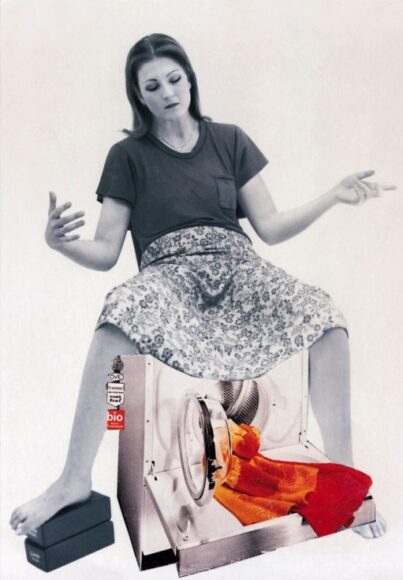

Thus Valie Export, previously an explosive performance artist associated with the Viennese Action movement — who could forget the dramatic self-portrait in which she points a machinegun at us while striding wide in a pair of crotchless biker leathers that show off her pubic mound? — has metamorphosed into a glum social satirist. She comments on her days of motherhood by photographing a woman in the pose of a Renaissance Madonna with a washing machine full of kids’ laundry pouring out from between her legs.

More beautifully, more poetically, Billie Zangewa from Malawi has sewn a silk hanging in which her young boy is asleep on the floor while the cloth around him unravels as if to signify an advancing threat. Considering we are talking about embroidered silk, it’s done with astonishing realism.

So precisely is the show curated that every artwork feels as if it is progressing the story. The talented Barbara Walker, who should surely have won the Turner prize last year when she was shortlisted, offers a mother’s lament on her teenage son’s recurring relations with the police. He’s been stopped and searched on numerous occasions. So Walker draws her images on the dockets the police sent her to add evidential poignancy to her retorts. With kids, the urge to protect them never diminishes.

Cassie Arnold, from Texas, provides the event with one of its showstoppers: a little girl’s school outfit knitted from Kevlar, the material used to make bulletproof vests. In everyday Texas, every child needs one.

As I said, the “MAINTENANCE” section is in the wrong place here and only when you climb upstairs do you encounter the show’s rightful beginning. It’s a tribute to “CREATION”, in which the display winds back to the beginning: the days of pregnancy and expectation.

In 1977 Susan Hiller began taking weekly close-ups of her expanding stomach. They are exhibited in a minimalist sequence like the phases of the moon. Less pleasantly, less positively, Dorothy Cross commemorates the “joys of breastfeeding” in a harsh sculpture in which a baby’s pillow has been stitched together with a cow’s udder. In a show ripe with negativity, Cross’s bovine teats wobble with special dismay.

At the centre of it all is a large gallery called the Temple in which a ring of female self-portraitists tackle the state of motherhood in a lively sequence, packed, again, with unexpected issues. Chantal Joffe, a veteran of the territory who has devoted much of her recent art to her daughter Esme, shows herself sitting topless in saggy pants while her moody offspring sulks next to her on the settee. The topless mother looks straight at us. The sulking child stares at the floor. Like so much of the art here, it features the child, but is principally about the parent.

None of the artists who continue the story — Paula Rego, Tracey Emin, Ishbel Myerscough, Catherine Opie — says anything straightforward about motherhood. The image of uncomplicated joy that art has generally proposed is recurringly outed as a masculine projection. Yet still we do it, still we need it, still we want it.

In a final section, poignantly labelled “LOSS”, we witness various failed attempts at pregnancy and their bleak consequences. Another of the show’s masterpieces, a photographic story by Elina Brotherus in which she remembers her numerous attempts at IVF, plunges us deep into the artist’s depression.

The sequence is called Annonciation, after those old master paintings in which the Angel Gabriel tells the Virgin Mary she is going to have a child, and that the child is going to be Jesus. In Brotherus’s tragic version there is no child. Only the hope, the wait, the sadness.

Acts of Creation: On Art and Motherhood is at the Arnolfini, Bristol, until May 26