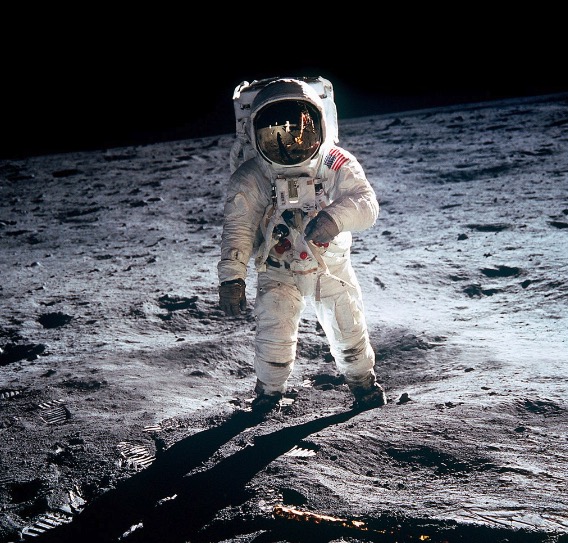

It’s July 20, 1969. Just after 8pm. A crucial moment in the space race. In a few minutes man will be landing on the moon. Or will he?

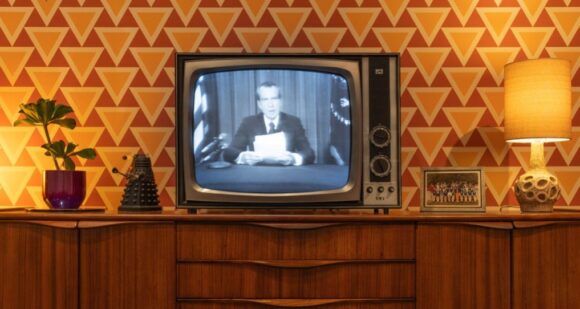

You’ve been glued to the television all day. The school gave everyone a holiday to witness the big finale. In Houston Mission Control is buzzing with last-minute instructions. On the telly, in blotchy black and white, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin are floating around the lunar module completing touchdown preparations. The Eagle is landing.

You take a bite out of the gigantic Mars bar you’ve been saving for the evening — they really should make these smaller — and start chewing excitedly. But suddenly the screen starts wobbling. Buzz, buzz, buzz. Something’s wrong … The telly goes black.

Flicker, flicker. Bleep, bleep. Slowly, the picture returns. But it isn’t the moon you’re seeing, it’s America’s president, Richard Nixon, at his desk in the White House, looking glum. He has news. And it’s bad.

Tricky Dicky begins his monologue: “Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace.” Adopting his most serious, most simian face, Nixon goes on, his voice deepening and slowing to a crawl. “These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice …”

A tear slips down your cheek. And plops on to the Mars bar. Poor Neil. Poor Buzz. Poor mankind.

I’m fantasising. But that’s what you’re supposed to do in the provocative installation that has arrived at the Sainsbury Centre in Norwich and which has set out to examine what is and what isn’t the truth.

In a carefully recreated 1960s living room, with vintage telly and model Dalek, the artists Halsey Burgund and Francesca Panetta have Tardis-ed us back to the night of the moon landing and confronted us with a scenario that didn’t happen. Where the Eagle didn’t land. Where Armstrong and Aldrin didn’t make it.

The words Nixon is solemnly intoning from his desk were actually written. Nixon’s speechwriter William Safire knocked them out after Nasa suggested it might be smart to have something ready in case the Apollo 11 mission went wrong.

“You want to be thinking of some alternative posture for the president,” Nasa advised, “like what to do for the widows.” So Safire knocked out an alternative posture. Now, using AI technology, complemented with historical archive, Burgund and Panetta have deepfaked Nixon delivering it. It’s called In Event of Moon Disaster, and the results are anxiously convincing. Sweaty and shifty as ever, evil Dicky plagiarises Rupert Brooke: “For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.”

And even though you know it’s a fake, even though Nixon was cursed with the kind of face you can never trust, something inside feels soppy. Because that’s what words can do to you. It’s what art can do to you.

Burgund and Panetta’s clever hoax, developed with the help of MIT in Boston, was made in 2019. Since then things have rushed crazily ahead on the deepfake front. As you sit in your 1960s living room, watching your 1960s telly, listening to a 1960s president, your thoughts turn, inevitably, to today. To where we are with AI. To all those antivaxers, flat Earthers, Holocaust deniers, 9/11 truthers and QAnon-ers who have been telling us all along that the moon landing never happened.

The Nixon installation is part of a six-month investigation at the Sainsbury Centre called What Is Truth? Various artists in various territories will be questioning the veracity of what we see in a world in which reality is beginning to feel inconveniently unconvincing. Thank God, art is there to investigate the truthfulness of the truth and offer a soupçon of solace.

There’s a lot going on at the Sainsbury Centre. Not content with ploughing up reality, the gallery is busily rethinking the definition of a museum. In the latest rehang you can stroke a sculpture by Henry Moore; lie on your back and look up at a Giacometti; do a dance in the Tang style while examining 7th-century Tang dancers rescued from a Chinese tomb. In this bandit rehang the rules for visiting a museum are being reconsidered.

The centre is the baby of Lord and Lady Sainsbury, kindly supermarket magnates who were frantic collectors of art. The Sainsburys gathered “world art” from Africa, China, Cambodia, Mexico, Japan, India and Polynesia, and scattered it about their home. They also collected western art — Francis Bacon, Alberto Giacometti, Amedeo Modigliani — and this too they dotted about in interesting mixes.

When the time came to set up their museum, built on the fringes of the University of East Anglia in 1978, they insisted their domestic mash-up be respected and that Norman Foster should build the museum. The result was one of the most celebrated buildings in Britain, with big views and looming glass.

Unfortunately, Foster’s museum is under scaffolding. The glass is cracking. The roof is leaking. But if you squint when you arrive you can still sense that a progressive rethink of the museum set-up is being mounted here.

You can also fret about the provenance of the fabulous stash of African, Egyptian, Greek, Mexican, Indian, Cambodian and Japanese art that is the museum’s principal joy. Where did it come from? Do they want it back? As I said, there’s a lot going on at the Sainsbury Centre. And it’s all very now.

In Event of Moon Disaster is at the Sainsbury Centre, Norwich, until Aug 4