Lubaina Himid doesn’t like me much. There are plenty of good reasons for that — at least from her point of view. In the past I’ve been snippy about her work. I’m a middle-aged white man, her natural enemy. I’m straight. And in recent years I have shrieked loudly at the fall from grace of the Turner prize, an award she won in 2017.

Lots of reasons, then, for her not only to mistrust my opinions, but also to pinch my nose should we ever meet. Indeed, a while back on Twitter she expressed a scary enthusiasm to see me tossed into the air by an angry bull at a corrida, and to have my pants ripped by its horns! Ouch, ouch, ouch, squealed my inner matador.

All of which makes me a fearless and honest assessor of her work. So if I say her new show at Tate Modern is thunderously impressive, stirring, beautiful, bursting with creativity, you know you can trust me on this. There’s a caveat, which we’ll come to — an aesthetic problem I can’t shake out of my reaction — but it’s a small thing compared with the overall impact of this powerful event.

The exhibition isn’t really a retrospective, although some of the older work here dates to the 1980s. In those days Himid was an aesthetic activist determined to get black art noticed by a white art establishment that she loathed. The art she made then felt as if it was jabbing you in the chest. Its chief subjects — slavery, the crushing of black identity, the dark power of the sea — are still her chief subjects, but what was once explicit is nowadays implied.

The Tate show favours this later approach and presents us with an artist who is getting better and better. We begin with an array of colourful flags hanging above one of Tate Modern’s many foyers. Made in 2018 and inspired, I read, by east African Kanga fabrics, the boldly patterned banners, embroidered with enigmatic words of wisdom, bring something immediately demotic and human to the echoey concrete emptiness of the Blavatnik Building.

“There could be an endless ocean” reads a sad flag dappled in blue and grey. “How do you spell change?” asks a brighter one in red and gold. The colourful folk art flutterings feel as if they are challenging the strict modernist architecture that surrounds them like someone turning up at a funeral in a Hawaiian shirt. The show beyond turns out to be many things, but one of them is definitely an architectural critique of Tate Modern itself: its looming, inhuman proportions; its hard, masculine lines.

It’s quickly obvious as well that things are going to get noisy. As soon as you step in you hear whispers and groans. In the rooms ahead the whispers turn into music. And then into the sound of the sea, whose relentless rolling soaks into your thoughts and makes everything feel as if it is addressing the subject of slavery, even when there’s no obvious reason to think that.

The inventive noise moments are collaborations with Magda Stawarska-Beavan, a sound artist with whom Himid has been working for a decade and whose impact has obviously been transformational. Most of the best pieces in the show have a sound element to them.

Metal Handkerchiefs is a set of folky paintings of tools and building materials of the sort you might buy from B&Q — saws, hammers, nails — quintessential boy’s stuff that brings joy to the DIY giant lurking inside every bloke. By painting them in unexpected colours and surrounding them with decorative frames, Himid softens the masculinity of the imagery and claims it for the feminine side.

It’s an effect continued in the readings from a health and safety guidebook that complete the piece. To a moody Stawarska-Beavan’s soundtrack of sighing machines and groaning technology, the reciting Himid manages to turn factory prose into something unexpectedly poetic. “Allow for short breaks,” she suggests breathily to the soft toing and froing of a saw. “Work from underneath,” she whispers, suggestively, to an image of a pulley. Masculine instructions are being repurposed with feminine rhythms.

Even better is the show’s masterpiece, a 2020 work called Blue Grid Test in which a mysterious frieze of household fragments — bits of furniture, some books, bits of piano, a banjo — are arranged along the wall and held in place by a line of blue decoration that stretches around the room like a horizon at sea.

No one mentions slavery or shipwrecks, but they pop immediately into your thoughts. No one mentions music, but still you feel its presence as the band plays on and the vessel sinks. All the time Himid’s deep and seasoned voice is intoning variations on the word “blue” in French, German and English. This is art working in the manner of some jazz improv.

In her earlier life Himid studied theatre design, and the way she uses sound to imply profound stuff without ever describing it and to blur one experience into another seems to me to involve the use of deep-seated theatrical skills. The result is a show in which all the bits feel intimately connected like a giant installation.

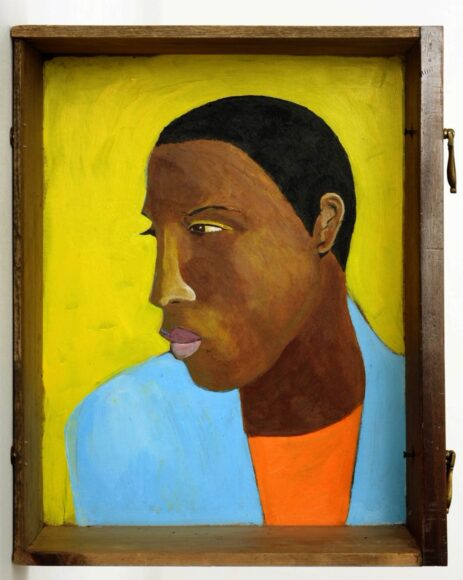

At the top I mentioned some caveats. What are they? Well, m’lud, I have a problem with Himid’s paintings. They comprise a large chunk of the display and work well enough on a smaller scale, notably with the black faces painted inside a set of secret drawers, or the so-called Feast Wagons, old-fashioned wooden carts on which she has painted a cast of foreign beasties, like those lethal spiders that pop up occasionally in bunches of imported bananas.

But the folk art simplifications that bring directness and urgency on a small scale look inelegant and clunky when transferred to the big history paintings that complete the event. On an enlarged scale the folky figures look wooden rather than charming. The acrylic colours bring moods that belong on posters. And the fluency of her thinking hits the immovable rock of her stiff wrists.

These, though, are small caveats. Everything else here is bursting with ideas and packed with fine moments.

Lubaina Himid, Tate Modern, London SE1, until Jul 3