Juxtaposing contemporary art with somewhere old — a church, a stately home, a museum — has become a popular display strategy. It’s easy to see why. Contemporary art has more of a buzz about it these days than old art. It feels younger, fresher. It fetches more at auction. Just as vampires need the blood of young virgins, so old places on the cultural map need an occasional spurt of artistic newness.

Unfortunately, the results are often unpleasant. Some of the ugliest sights I have witnessed in art have been juxtapositions of the old and the new. Michael Craig-Martin at Chatsworth was spectacularly bad: Barbie pinks and Paperchase blues clashed horrendously with the historic greens of Derbyshire. Even worse was Jan Fabre at the Hermitage in St Petersburg: heavy-metal art, fashioned from stuffed crows and dead beetles, was planted in front of Giorgione and Raphael. Urgh. So no, I wasn’t looking forward with confidence to Cecily Brown at Blenheim Palace.

Designed at the beginning of the 18th century by Sir John Vanbrugh for the 1st Duke of Marlborough, Blenheim is gigantic and pompous. Churchill was born here. Cecily Brown, on the other hand, is flickery and fidgety. Born in London in 1969, she trained at the Slade and then made the interesting decision in 1994 to move to New York. Internationally popular, she paints slippery pictures that could mean this, or they could mean that. Blenheim, you can’t miss. Brown, you can’t catch.

At Blenheim, she’s been let loose on the whole building and pops up at strange angles in unexpected corners of the palace. So what we have here is that reliable pleasure: a treasure hunt.

Her first offerings are four huge canvases inspired by the battle flag of the Duke of Marlborough, which hangs above the entrance to the Great Hall at Blenheim. The duke won lots of battles. His standard is packed with symbolic representations of all of them, like one of those camper vans you see plastered with stickers from everywhere it’s been.

Brown’s responses are hung around the walls at the same lofty height, just below a clunky baroque fresco by James Thornhill showing the duke presenting his plans for the Battle of Blenheim to Britannia. The Thornhill fresco is effortful and wooden. So, alas, are Brown’s responses. They try too hard to mimic the multi-part composition of the duke’s battle flag and end up as blurry paraphrases of it.

What is useful, however, is the light they shine on her methods. As I said, she’s slippery. Her work vibrates between abstraction and figuration. The redone flags make clear that she starts with something specific, then rows away from it. A figurative pebble is thrown in the water and she paints the ripples.

The flags don’t work. But the adventure ahead has some real successes. Apart from a couple of Van Dycks, the old master colection at Blenheim is disappointing, with little of note scattered among the crowd of scowling ancestors. A lot has been sold to pay the bills, including good examples of that country-house staple: the Flemish hunting scene.

As if to make up for these missing paintings of fox slaughter and boar torture, Brown has produced a suite of hunting pictures and scattered them about the palace. The best of these capture the rush and violence of the hunt without ever describing it, especially in the show’s most convincing interjection, in the Green Drawing Room, where the plush mirror above the fireplace has been elbowed out by a violent battle of hunting colours.

Dog Is Life, as the picture is called, made me think of Chaim Soutine and his savage animal carcasses. Slashed pinks — gory, visceral — speak instantly of animal death and mauling, while recurring combinations of red and green sneakily evoke the scarlet of the Cotswold hunt and its territory.

Brown, I read, is a vegetarian and an animal rights activist. So are there subversive ambitions at work here? Is this posh appearance at Blenheim a cover for a sustained prodding of England’s inglorious past? Yup. That’s exactly what’s going on. Under the cover of a posh appearance in a grand stately home, Cecily Brown is sticking it to the man.

Having had a go at the hunting history of the Marlboroughs, she aims next at their taste for warfare. Again in the Green Drawing Room, a marvellous fuzz of whites, greens, blacks and reds — called There’ll Always Be an England — manages somehow to describe a frenzied encounter between the white cliffs of Dover and the flag of St George without showing either. You know how iron filings follow the direction of a magnet passing under a table? It’s something like that.

She’s at her best in the small to medium-sized pictures that have moved furthest away from their sources. The more abstract she is, the better. Her least convincing moments are her most literal ones, where she paints overly big pictures in an effort to match her surroundings. The largest one here, a huge rework of the Triumph of Death in the Palazzo Abatellis in Palermo, in which a furious skeleton from the Book of Revelation rides a white horse into the apocalypse, is too literal to soar. The scale defeats her.

Yet elsewhere there’s more good than bad. Having accepted a daunting challenge, she manages to succeed in much of it. We learn a lot about her methods. And, best of all, she turns out to be an angry dog, snapping at the hand that feeds it. Which is what the better artists have always been.

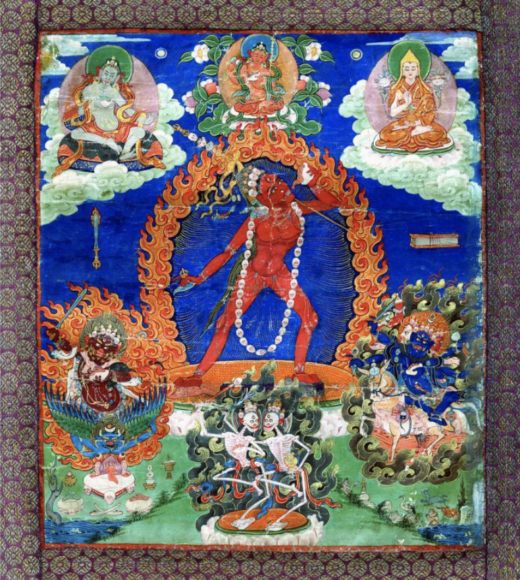

Still on the subject of transgression, Tantra at the British Museum is concerned with little else. If something disgusts, frightens, appals, obsesses or unbalances you, tantra’s message is: do it. Indeed, do it twice, thrice, as many times as you fancy. Because transgression is the route to power.

This is sure to come as a surprise to those of us who know next to nothing about tantra, except that it’s some kind of esoteric eastern belief allied to Buddhism, and that when Sting does it he can keep pleasuring his wife for seven hours at a stretch.

This fascinating show expands in every direction from these shoddy crumbs of knowledge. Tantra, it turns out, was a profound philosophical reboot that flourished in the eastern world from the beginning of the first millennium and weaponised the doubts and inequalities of its believers. Tantra was a threat to power because it empowered others, especially women.

The show argues all this with art objects, maps, installations and soundscapes that begin with a film, produced by Mick Jagger in 1969, whose psychedelic dreaminess leaves us in little doubt that the copious smoking of a chillum was involved in its conception. Taking drugs and having lots of sex were tantric rules that appealed mightily to the 1960s. But these beliefs need to be understood in different ways, the show insists.

What tantra seems really to have been saying was that the gods governed everything — including the basest human behaviour — and that by accepting this baseness, and plunging into it, tantric believers could free themselves from the power of others.

Some of the resulting sculpture, especially the tributes to Kama, the tantric god of desire, may well kill your granny, so I advise you not to bring her. Unless, of course, you wish, tantrically, for her passing. In which case, here’s a belief system that will forgive you.

Cecily Brown, Blenheim Palace, until Jan 3, 2021; Tantra, British Museum, until Jan 24