A couple of eternities ago, before the Great Lockdown slowed time to a crawl, I saw a remarkable exhibition at the Jewish Museum in London. I should have reviewed it there and then, but important events were opening all around and I missed the slot. It happens. Weirdly, though, the missed show has continued to nag at me, while the covered ones have mostly fallen silent. It’s as if the Great Lockdown has given it extra agency and power.

The show featured the work of Charlotte Salomon, who died at Auschwitz in 1943. She was 26 when they gassed her, five months pregnant with her first child. Born in Berlin in 1917, she had dreamt of being an artist, brought up by cultured Jewish parents to be musical, creative, confident in her aesthetics, thoroughly middle class. Salomon was supposed to be one thing, but turned into another. The last thing anyone expected of her was that she would become a murderer.

When the war broke out, she was sent to the south of France for safekeeping, where she lived with her maternal grandparents in a posh villa near Nice. Things had grown darker in Berlin, but on the French Riviera they turned a corvid black. By the time she was gassed, she was capable of writing that it was not “Herr Hitler” who “symbolised for me the people I had to resist”, but her grandfather. He’s the one she murdered.

We know about all this because, between 1941 and 1943, cooped up on the Riviera, Salomon created something extraordinary: a cascade of pictures, words, music, that she called Life? or Theatre? (Leben? oder Theater?). Unfolding across 769 pages, this torrent of images and words has the subtitle: Ein Singspiel. A Song Cycle. Think of it as a graphic novel that can be read while listening to a Spotify playlist. A generous selection of drawings, along with helpful biographical notes, was shown at the Jewish Museum.

We’ll come to the murder in a moment, but another reason why Salomon’s pictorial autobiography was so potent was its relentlessness. From beginning to end, it’s a car crash waiting to happen. In the text, she uses joky pseudonyms for the main characters, including herself, but it’s obvious who they all are. Or is it? A further reason I cannot get Salomon out of my mind is because I’m unshakably uncertain what to believe about her.

Her mother had a dark mental past. After several attempts at suicide, she killed herself in Berlin when Charlotte was eight. The family told the little girl her mother had died from influenza. Her father soon remarried, an opera singer called Paula Lindberg, who organised singing lessons for her stepdaughter with a cranky music master, Alfred Wolfsohn, an unbalanced lothario who fancied the stepmother, but on whom Charlotte developed a fierce crush. In Life? or Theatre?she calls him Amadeus Daberlohn. He’s her first lover, and the focus of a large chunk of this paper happening.

The rise of the Nazis — summarised brilliantly in rapier-swift tumblings of images and words — halts her artistic career, and she’s sent to France. It is in the house of her grandparents that she discovers her real past. And the crows start to circle.

It turns out that the maternal branch of her family is riddled with mental darkness. Her grandmother tries to hang herself in the bathroom while Charlotte is there. When that doesn’t work, she poisons herself and finally throws herself out of a window. Her grandfather begins tormenting her with grim truths about her blighted genes and, perhaps, subjecting her to sexual abuse. Life? or Theatre? isn’t clear about it. Charlotte finds out about her mother’s suicide, and also that her aunt, her great-grandmother, her great-uncle and her grandmother’s nephew killed themselves as well.

While this dark family history is being heaped on her, the present is giving her a kicking. She’s sent to a camp in the Pyrenees. She gets out. Returns to Nice. Meets and marries a German-Jewish refugee. Gets pregnant. And murders her grandfather with an omelette laced with the barbiturates her grandmother had been stockpiling.

Not all these details are in Life? or Theatre? The poisoning of her grandfather was a family secret, only revealed in 2015. But with Salomon, facts, images and imaginings have a tendency to blur. Working with quick- drying gouaches that respond immediately to her speediest thoughts, she combines cascades of imagery with dense overlays of superfast text. Images and texts have the kind of relationship that exists between speechmakers and signers; one is an instant response to the other. As the work progresses — as her life and history spiral — the interplay grows more frenetic.

Interestingly, she was a fan of German expressionist cinema, and the jagged rhythms of her tumultuous life are tangibly reminiscent of Fritz Lang or The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. The way everything happens at once. The feeling you have hopped into another dimension. The underpinning of darkness. The dreamy unreality.

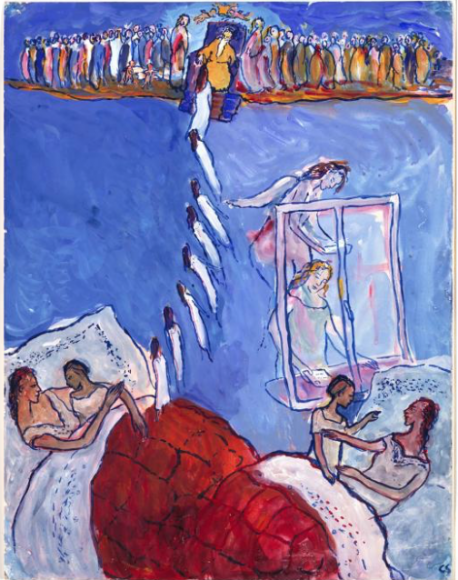

A good example is an image in which Charlotte shows herself in bed with her mother, who is telling her daughter about Heaven and promising her that when she dies she will return to earth as an angel and will describe everything to her daughter in a note she will leave on the windowsill. It’s all in the drawing: the two of them in bed; the mother going to Heaven; Heaven as busy as a station platform; the angelic return to earth; the windowsill; the note; the bed. All these timescales and dimensions have somehow been concertinaed into a single image that feels simple rather than frantic, innocent rather than complex. Only when you begin to apply the overlays of text does it grow darker and denser.

These are fascinating methods. The Jewish Museum was keen for Life? or Theatre? not to be included in the sad category of Holocaust art, and to be recognised as something loftier, so it was presented as a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art in the manner of Wagner. Salomon had suggested specific pieces of music to accompany her images and words, and the Jewish Museum had obliged.

But Life? or Theatre? doesn’t need any beefing up. The drawings are furious, inventive, exciting. The storylines weird and involving. The mix of truths, half-truths and imaginings a constant test. And it’s all so slippery. I’ve been trying to pin down why the damn thing has been haunting me, and I think it’s because Salomon’s humanity feels like an intimate gift from a passing stranger. As if she’s slipped her inner life into our pocket when we didn’t ask for it. Her isolation speaks to our isolation. And right now, I am in the mood for compelling whispers.