What a clever idea for a show. By focusing on couples rather than individuals, Modern Couples, at the Barbican Art Gallery, has found a new way to arrange and understand modern art. This noisy event reshuffles the pack and invents a whole new game of poker: “OK, Slim. I’ll see your Picasso. And I’ll raise you a Dora Maar…”

The old storyline the show wants to rip up is the one that sees the progress of modern art as a relay race for male geniuses. First there was Matisse, then Picasso, then Kandinsky, and so on. It’s a progression whose origins can be traced back to the opening of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, in 1929. As the world’s first museum of modern art, MoMA came up with the first paradigm, and it has held sway, more or less, until now.

Here, though, it is attacked from every angle in the circumference — on gender lines, on ethnic lines, on class lines, on political lines, on psychotherapeutic lines, on the lines of sexual orientation. Whatever your line, you can be certain that someone at this Babylon of contemporary positioning is pursuing it.

By focusing on couples, and occasionally on threesomes — heterosexual, homosexual, sapphic, platonic, plus assorted amalgams — the exhibition writes a new plotline for modernity. Featuring more than 40 artistic pairings — Rodin and Camille; Frida and Diego; Pablo and Dora — it’s a Love Island of a show that celebrates artists as social beings and presents their interpersonal relationships as the wellspring of their art. Oh, and there’s a big dollop of Strictly thrown in, with some hair-raising tales of bed-hopping, betrayal and transgressive snogging. The result is an event with its finger so firmly on today’s pulse, I’m surprised it didn’t make the cover of this week’s Hello!.

I’m being cheeky. Although the focus on couples is trendy, it proves also to be genuinely revealing. The relationship between Rodin and Camille Claudel has generally been understood as a classic example of the “old man takes young girl” preference of the patriarchy. Rodin was in his forties when he met Claudel; she was 20. He was an established “genius” of modern sculpture, she was his talented victim.

To its credit, however, the present event refuses to rush to condemnation. On the contrary. By confronting us with intimate examples of their shared output — entwined couples in the main, with enough erotic charge to light a skyscraper — the opening display directs our attention away from the inequality of the relationship towards its artistic explosiveness. He may have been old, she may have been young, but both lit big fires under the other. “I go to bed naked every night, to make me think you’re here,” she writes to him in one of the exhibition’s many startling letters. “I kiss your hands, my sweetheart — next to you my soul can exist,” he replies. The British Museum’s recent Rodin show, huge though it was, had nothing in it as revealing as the brief exchanges gathered here between Camille and Auguste.

Thus, the overarching theme at the Barbican — love conquers all — reaps immediate rewards, and continues to do so for the dozens of relationships examined in the spaces ahead. All the couples, or threesomes, get a booth to themselves in the fashion of an American diner. Every booth mixes examples of their work with appropriate lashings of documentary information — letters, photos, biogs, keepsakes.

In most instances, it’s an approach that proves transformative. Marcel Duchamp, imprinted so firmly in our artistic imaginations as a stick-dry conceptual presence, turns into wobbly love jelly in the company of the Brazilian sculptor Maria Martins, who took him, then left him. Having cast Martins’s naked body for his final masterwork, Duchamp turned intimate bits of her — the imprint of her crotch, the crease beneath her breast — into fetishistic sculptures he could carry in his pocket and fondle.

Virginia Woolf, an inevitable heroine, makes her first appearance as the lover of Vita Sackville-West. “I am reduced to a thing that wants Virginia,” drools Vita in one of those sizzling letters. “I feel like a moth, about to settle in a sweet bush,” drools back her bedmate, “— would it were, ah but that’s improper.” The next time we encounter Virginia, she is the loyal wife of Leonard Woolf, and together they are altering the course of modern British literature by founding and running the Hogarth Press.

Thus the fluidity of sexual taste sends the exhibition scarpering in all directions. Having expanded the scope of the relationships it seeks to feature — from heterosexual to sapphic, from artistic to literary — it begins now to introduce us to creatives of whom most of us will not have heard. Either because their partners stole the limelight — Emilie Flöge and Gustav Klimt; Benedetta and Filippo Tommaso Marinetti; Unica Zürn and Hans Bellmer — or because their contributions fell outside the old territory of modernism.

The cocky American threesome known collectively as PaJaMa — Paul Cadmus, Jared French, Margaret French — were pioneering photographers whose torrid homoerotic images were produced against an interwar backcloth of repression and illegality.

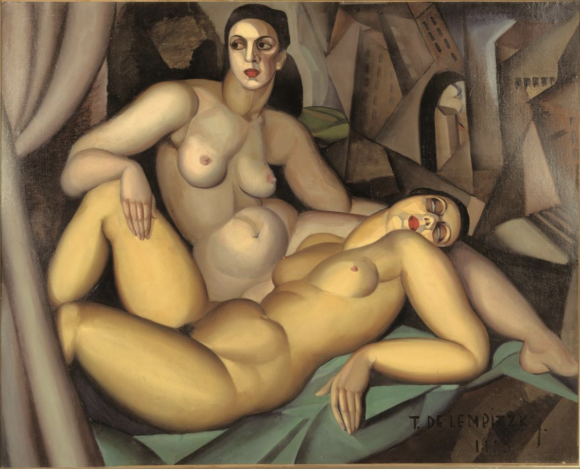

In Paris in the 1920s, Natalie Clifford Barney held naughty Friday-evening salons — called the Temple of Friendship — specially for lesbians. Barney’s American lover, Romaine Brooks, is represented by a couple of elegantly grey female portraits, while Tamara de Lempicka, being Polish rather than American, gets straight to the point with a huge cubistic portrayal of two nudes in a bed. One of the girls has slumped into exhausted sleep, and it’s not from watching the telly.

Desire and artistry seem here to be joined at the hip. All the couples we encounter — Sonia and Robert Delaunay; Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera; Lucia and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy — seem to profit from each other’s presence. Another excellent outcome of this inventive slicing of the cake is the unpredictable route it forces the display to take. One minute we are among French cubists. The next it’s Viennese secessionists. Czechoslovakia’s sadomasochists will shock you. Quick hop and you’re in revolutionary Mexico. Every jump is a surprise.

What we really have here is 40 pint-sized shows disguised as a single journey. Inevitably, some work better than others, but the good ones are spectacular. The love booth devoted to the cuddling Russians — Alexander Rodchenko and Varvara Stepanova; Vladimir Mayakovsky and Lilya Brik — is worth the admission price on its own. To organise all this must have been horrendously difficult. The curators deserve a medal for bravery as well as for effort.

At the Whitechapel Art Gallery, Michael Elmgreen and Ingar Dragset are another lovey-dovey couple enjoying a notable success. Although Elmgreen & Dragset are no longer lovers, they remain collaborators, and their Whitechapel show skips nimbly from idea to idea.

Their main shtick is to create fake ambiences, and to present them so accurately that we mistake them for the real thing. The opening sight here is a decrepit swimming pool that takes up the entire ground floor and seems to have been abandoned. The paint is peeling. The skylights are cracked. There are slugs on the timbers.

A caption tells us that the Whitechapel Pool was built in 1901, that it served the local community for a century and even inspired the first of David Hockney’s pool pictures. Alas, it has now been sold to a foreign developer and will reopen as a bijou hotel.

It’s all lies, of course. But lies with a ring of truth to them. This particular pool may never have existed, but its real-life cousins have and do: the storyline may be false, but there is nothing false about the harsh economic truths it seeks to convey. Goodbye, local community. Hello, Oleg Oligarch. Will that be Krug or Cristal, sir?

Modern Couples, Barbican Art Gallery, London EC2, until January 27; Elmgreen & Dragset, Whitechapel Gallery, London E1, until January 13