Spellbound, an exhibition about magic, ritual and witchcraft that has opened at the Ashmolean Museum does not need to try very hard to persuade us that magic, ritual and witchcraft remain pertinent in the modern world. On the contrary. The evidence for a global collapse of reason is overwhelming.

I don’t just mean all the sword and sorcery that continues to clog our TV and cinema screens, with its Hobbit-Hugging and its Gaming of Thrones. The modern hunger for unreason is every bit as evident in the tattooed iguana curling up the neck of that bank executive sitting opposite you on the Tube, or in the giant block of warrior surrealism etched into the front and back of David Beckham. Someone give the poor man a slot on a cage-fighting bill before he tattoos himself into invisibility!

I don’t just mean all the sword and sorcery that continues to clog our TV and cinema screens, with its Hobbit-Hugging and its Gaming of Thrones. The modern hunger for unreason is every bit as evident in the tattooed iguana curling up the neck of that bank executive sitting opposite you on the Tube, or in the giant block of warrior surrealism etched into the front and back of David Beckham. Someone give the poor man a slot on a cage-fighting bill before he tattoos himself into invisibility!

Personally, I would throw in the current taste for bushy beards as further proof of a growing appetite for the irrational. What is a beard if not a display of ersatz primitivism, a siding with the barbarians against the Romans? As for our politics — the facts are glaring. America’s preposterous en-Trumpment only becomes explicable if we recognise it as the casting of a blind spell by a society that has taken to nailing vulture wings to the barn door. The same goes for Brexit. In sensible terms, it makes no sense whatsoever.

Spellbound does not mention any of these things, but the show’s mood is informed by all of them. Indeed, the very fact that witchcraft is being examined in a serious exhibition at the Ashmolean Museum, in Oxford of all places, feels like further evidence of the triumph of unreason. We know already that contemporary art is chiefly in the business of supplying mystery and senselessness to a society starved of both, but now the historical shows are at it as well.

Not that Spellbound is an examination of anything overly tangible. It’s more hotchpotch than journey, a cauldron of bubbling artefacts, cursed with varying degrees of spookiness, thrown into a subfusc mix that feels stubbornly random. One moment you’re staring at a dried toad stuffed with thorns, and the next it’s a padlock removed from a bridge in Leeds on which Sam has pledged his unbreakable love for Kirsty. Previous epochs did it with eternity rings. We do it with padlocks from Homebase.

As the rationale for this event, the show’s organisers, Dr Sophie Page and Professor Marina Wallace, propose that we are living through an epoch that places greater trust in our emotions and the messages of our “interior lives”: in what we feel, rather than what we know. This makes us a sympathetic audience for a broom ride into the magic and superstition of the past, because magic and superstition are instinctive responses to the “key emotions of love, fear and rage”.

The opening point, that our magical past survives in half-remembered superstitions and dimly observed rituals, is made cheekily by a ladder under which you duck to enter the twilight. The display beyond hurries through the various forms of superstition and thaumaturgy that thrived in the medieval world and continue to have a contemporary resonance. You certainly don’t need to be Mystic Meg to recognise that the beautiful examples of medieval cosmology gathered here in glass cases survive in bastard form in the daily horoscope.

Here and there, specially commissioned bits of contemporary art loom up from nowhere in an effort to connect now with then. Thus, a large astrological weaving covered in skulls and zodiac signs, made by prison inmates in 2018, is the latest example in the show of an insistent awareness that we are but tiny specks in the giant workings of the cosmos; and that magic is our hopeless attempt to affect forces greater than us.

It’s probably true. But the way the exhibition makes this kind of point, in clunky wall texts that oscillate uncertainly between baby talk and evening-class jargon, left me hurting inside, as if I’d eaten a sheep’s heart stuffed with pins. Is this the level of understanding to which the academic mind in Oxford is currently aspiring? The return to unreason is depressing enough. The concurrent championing of a lifestyle-supplement magic, gluten-free and packed with goodness, had my toes curling.

I wish Dr Page and Prof Wallace had not opined on the first catalogue leaf I opened that “just as the image of a pipe is not a pipe, as the surrealist Henri Magritte demonstrated, magical thinking confuses reality with dreams”. I want my professors and doctors to excel at scholarly exactitude, and never to confuse Henri Matisse with René Magritte. Indeed, it’s what I expect of them.

By far the best thing about this show is the occasional genuinely spooky exhibit that pops up to remind us what strange minds we humans have, or had, and how far from the path of reason we have recurrently strayed. A pretty little glass bottle, silvered inside, collected in Brighton in 1915, was said by the old woman who owned it to contain a witch, and “if you let un out there’ll be a peck o’ trouble”.

Certain substances turn out to be inherently magical. Rock crystal, frozen water as the medieval world understood it, had all manner of magic uses. A beautiful ceremonial sword that may have belonged to Henrietta Maria, the Catholic bride of Charles I, has a rock crystal hilt, inside which nestle the protective bones of a saint. The notorious Elizabethan alchemist John Dee owned a crystal pendant that he said was given to him by the angel Uriel. Dee’s black obsidian mirror served also as a portable home for spirits.

While magic in the Middle Ages still feels loosely connected to the pursuit of knowledge — indeed, it strikes you as a version of it — by the time we reach the 17th century, the bottom has fallen out of reason and a proper creepiness has set in. The grotesquely stuffed cat and rat found walled up in a chimney in Norfolk were probably intended as a magical form of vermin control. The house owners were trying to ward off rats on a cosmic level.

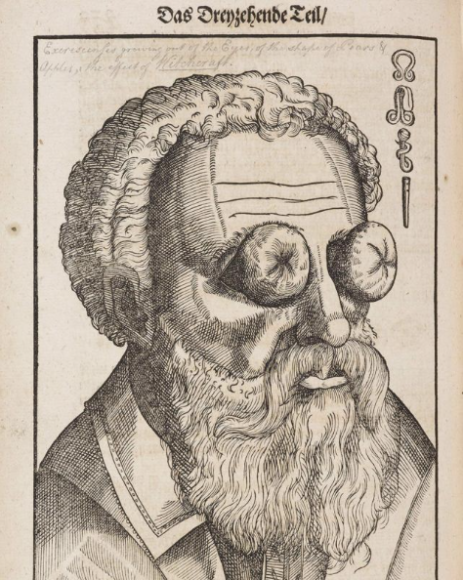

The final section deals with witches. It’s where the best art is found, especially among the German Renaissance prints of scary hags ensuring our fall with a deadly mix of eroticism and necromancy. The show sees the history of witches, and the terrible cruelties visited on those suspected of being witches, as the demonisation of women and an outrageous expression of masculine fears. I’m sure that’s right.

But an event that pursued knowledge more actively than this one might have gone on to examine how the #MeToo witches were descended from the biblical presentation of Eve as the first transgressor, and how the sinful awareness of our expulsion from paradise enlarged the fear of satanic women. But that would have made this a genuinely scholarly effort, and, in the modern world, scholarship is something you shove up the chimney.