I only saw Michael Jackson once. Unfortunately it was at the Brits in 1996. At the time, I was briefly head of music at Channel 4, and going to the Brits was part of the package. Jackson was receiving a special “award” as Artist of a Generation, but the real reason he was there was to re-sculpt the awful publicity that had been swirling around him since the levelling of sexual abuse charges against him by the family of Jordan Chandler. The Brits appearance was supposed to be a corrective. All it did was make everything worse.

Pop stars love to leave their fans begging hopelessly for their idols to appear, and on that particular night Jackson must have broken some sort of world record for irritating foreplay. On and on we waited. Eventually, the opening throbs of Earth Song began vibrating through the smoky air and, up in the heavens, a shadow stirred. Suddenly, there he was, descending to earth on the arm of a wonky crane, trying desperately to appear messianic. It was ludicrous. But what happened next was worse.

On the stage, a crowd of beggars, lepers, rabbis, frightened-looking women in biblical robes and, above all, lots of children dressed like tragic ragamuffins in a Murillo painting, began skulking out of the dark. When Jackson finally descended from the clouds, posed as Christ, complete with outstretched arms and backlit halo, the lepers and ragamuffins began to touch him and hug him, one after another, like invalids at a miracle.

It was at that point that Jarvis Cocker ran on and showed him his arse, a valid and conspicuously British response to the monstrous salvational pantomime being enacted for us on the stage.

I remember all this because the Michael Jackson exhibition that has opened at the National Portrait Gallery is a hagiographic event that should certainly have included more questions. Portraiture is not the same thing as flattery. Proper portraiture handles bad news as well as good. This show, curated personally by the director of the NPG, Nicholas Cullinan, is transparently a fan’s show that tells us more about the adoration of its makers than it does about Michael Jackson.

That said, the adoration of idols is as significant a phenomenon today as it was in the biblical epochs imagined so crassly at the Brits in 1996. And, even though this is more often a portrait of Michael Jackson’s idolaters than of him, there is plenty here to evaluate and note. Indeed, in its mirrored fashion, it’s surprisingly revealing.

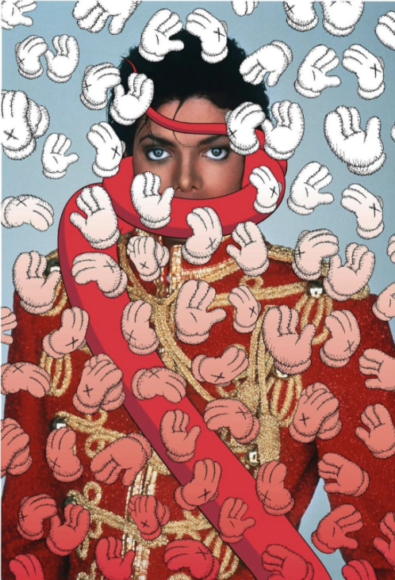

No pop star has inspired as much art as Michael Jackson. Or so we are told. Painters, photographers, video artists and installation makers have all turned to him for subject matter and inspiration. Their tributes pack the exhibition galleries of the NPG, while an insistent soundtrack of his music completes a busy experience.

Actually, of the 48 artists included here, a hefty number were commissioned to make work specially for the show. Paying tribute to the singer was the NPG’s idea, not theirs. It doesn’t make their contributions less interesting, but it is an insight into the mechanics of gallery hype. Michael Jackson may have been interested in art, but he wasn’t as interested as the reputation-shapers are now seeking to persuade us.

The slippages in reality that define him, and this show about him, are made quickly obvious by the huge equestrian portrait that looms up in the first alcove. Painted by Kehinde Wiley and completed in 2010, a year after Jackson’s death, it’s a straight steal from Rubens’s portrait of the Spanish king Philip II and shows the King of Pop on a white horse, riding through a field of battle in gilded armour, while two hovering putti crown him with laurels. The Rubens was about 8ft by 7ft. The Wiley is about 11ft by 10ft.

It’s a preposterous picture. The artist, who later painted Barack Obama sitting in a hedge, has a dry, characterless touch that makes his enlargement of Rubens feel like a giant magazine illustration. Yet for all its lack of subtlety, there is something poignant about the divergence between Jackson’s image of himself and the pitiful reality it masked. Wiley, to his credit, has amplified the sadness by adding his own symbolism. The horse now stands on the edge of a precipice. And the bouquet of red ranunculus that has sprouted in front of it is being eaten by a snail. It’s a vanitas detail borrowed from Flemish still lifes, intended as a comment on the transience of youth.

In every corner of the show ahead, Jackson finds himself showered with artistic love. Often with ludicrous results. David LaChapelle, a photographer entirely unfamiliar with the notion of restraint, is guilty of the biggest slippage of taste and sensibility, in a series of giant photographs that cast Jackson as Christ. They culminate in a Pieta in which he lies dead in the arms of a long-haired Jesus lookalike who has taken the place of the Virgin Mary.

Just as silly, though less expected, is Isa Genzken’s golden collage in which images of the dancing Jackson are compared to Stefan Lochner’s sublime Renaissance altarpiece of the Adoration of the Magi in Cologne Cathedral. In the next picture, Genzken attempts a second absurd comparison with Michelangelo’s David!

Anyone looking for further proof that Jackson triggered strange mash-ups of desire and motherliness in older women artists need only look at Lorraine O’Grady’s wall-load of sepia-tinted pin-ups, in which his dreamy likeness alternates with that of Charles Baudelaire. Even Maggie Hambling, of all people, seems to be hugging him as much as painting him, in a sad portrayal of a tragic waif lost in a fantasy world. Not even Bernard Buffet was as sentimental as this.

But the show isn’t all wall-to-wall kitsch. David Hammons, so often a voice of maturity at this kind of event, gives us a telling installation, “Which Mike do you want to be like?”: three microphones at different heights are tasked with standing in for three black American heroes: Michael Jordan (tallest), Michael Jackson (second tallest), Mike Tyson (shortest). What can a young black man aspire to be today, the sculpture seems hopelessly to be asking. A singer, a basketball star, a boxer?

Jackson’s problematic blackness is also the focus of a set of wall reliefs by Todd Gray, who used to be his official photographer, but who has since moved to Ghana. By combining recent Ghanaian imagery with photographic fragments of Jackson in his prime, Gray seems insistently to be comparing fact with fiction: the humble truth with the ornate fantasy.

So one thing Michael Jackson definitely did was breathe new life into the old meaning of the word “idol”. There was me thinking he had overplayed the messianic bit at the Brits, but at this show, exhibit after exhibit seems to confirm our continuing hunger for divinities to look up to and iconic fantasies to believe in.

Michael Jackson: On the Wall, National Portrait Gallery, London WC2, until Oct 21