Aftermath is a word that carries a tangible emotional clout. There’s something immediately dark about it, a mood without a light switch. The Rolling Stones used it as the title of my favourite album by them, the one with Mother’s Little Helper on it, and Stupid Girl and Under My Thumb, songs with an insistently bitter edge. And now Tate Britain, in a rare success in the nomenclature department, has used it to describe the best theme show mounted there in recent years.

To be honest, I was not expecting to admire Aftermath. Not because a display with that title was bound to be dark and gluey. In my book — the book of a sentient contemporaneity — dark and gluey is always appropriate. This, though, was yet another event prompted by the centenary commemoration of the First World War and, frankly, there have been a lot of those. Ever since the red poppies flooded the grass around the Tower of London — back in 2014! — show after show has sought to find new ways to remember what Michael Gove, in his pre-Brexit education moment, described as “a uniquely horrific war”. So yes, reader, I was suffering from First World War exhibition fatigue and casually assumed everything possible on the subject had been said.

But no. What had not been dealt with was the aftermath: the disfigured faces, the amputated limbs, the deranged minds, the emotional vacuums, the blown-up towns and families, the wretched hunger for normality, the extraordinary madness that descended on ordinary places and, perhaps most tellingly, the twisted and violent transformation of sex into an act of barbarity. Here, love-making becomes hate-making. When war scrambles humanity, it does so at the core.

The second thing the show does differently is to travel beyond the boundaries of Britain to include artistic responses to the conflict in France and Germany. I have, in the past, scolded Tate Britain for appearing to loathe its national obligations to art. Ever since it became Tate Britain, it has been obvious that this tricky branch of the Tate empire was embarrassed by the whole idea of Britishness and wanted desperately to avoid it. I suppose that is what is going on here, too. In this show, Germany’s role is to be the biggest victim, not the biggest enemy.

For once, Tate Britain’s out-of-step-ness with the national mood reaps some positive results. To put it bluntly, in matters of art, the German aftermath was more plangent and powerful than our own. A war as sick and unlovely as the Great War was no place for British reserve or artistic subtlety. What was needed was a response that threw itself among the corpses and tore up the rule book. And that is what German art provided.

We begin with the war itself, and picturings of its horror by friend and foe. The previously underestimated William Orpen, whose stock has risen notably during the Great War commemorations, makes another compelling appearance with a poignant view of the trenches into which you need to stare carefully to discern the homemade grave planted among the broken trees and the orphaned helmets.

The discarded helmet turns out to have been adopted by all sides as a stand-in for the departed soldier. A vitrine of rusty headgear — German, French, British — makes the notion touchable. But the most plangent painting here is Felix Vallotton’s view of the military cemetery at Châlons-sur-Marne. It features row after row of neat crosses, and although we have seen such views before, often, the wheatfield of death never fails to pluck a heartstring.

The show then begins its intriguing meander through war’s aftermath. The first of the windings takes us on a brief tour of the memorials erected after 1918. If the Cenotaph in Whitehall had not been commissioned immediately from Edwin Lutyens, where would we have been able to prompt the collective grief of the nation every November?

However, is the very British blankness that Lutyens settled on — an abstract block of stone, with no descriptive passages on it — the best way to do these things? Or does the opposite approach of Charles Sargeant Jagger, another artist whose star has ascended in the era of the war show, give us more to be tearful about? Jagger’s gripping Royal Artillery Memorial in Hyde Park, evoked here with smaller preparatory sculptures, makes war feel like a brutal human moment, where Lutyens’s Cenotaph presents it as something theoretical and shapeless.

Until now, the show has felt informative and helpful, but not yet rousing. That changes with a thematic room devoted to Traces of War, where we are suddenly splattered with gory doses of horror. It commences with Henry Tonks, the British war artist who had trained initially as a surgeon. Tonks presents us with a set of portraits of British soldiers disfigured in the trenches. Mouths torn open. Eyes bleeding. Cheeks disappeared. It’s a harsh visual reminder of what we are really examining here: the aftermath of war.

It is also now that the German contribution starts to enlarge. (The French presence spends most of the exhibition feeling faint and added on.) Tonks recorded his torn-up faces for documentary reasons, but when German artists address these same issues of disfigurement and human damage, they barge us brusquely into the darker realms of symbolism and surrealism. Heinrich Hoerle’s Cripple Portfolio, from 1920, is a shockingly effective set of images of the sufferings, physical and mental, of blown-up German soldiers. The most haunting scene, called The Man with the Wooden Leg Dreams, shows a stumpy figure, with no arms or legs, sitting in an inappropriately elegant chair, staring with horror at a cluster of flowerpots in which a heartless crop of gesticulating fingers and toes has sprouted. Nothing in British art matches the sheer savagery of Cripple Portfolio.

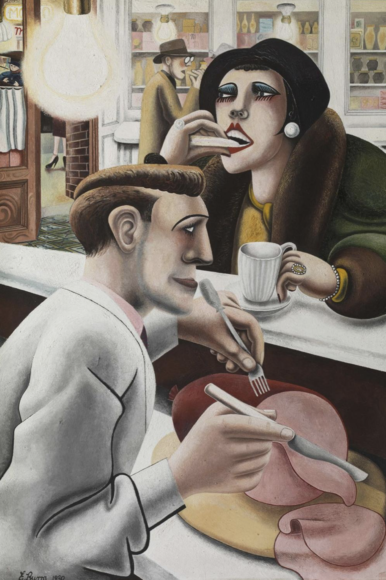

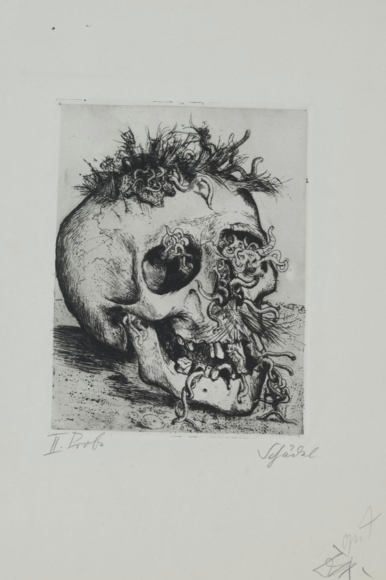

From here on, the show makes evident that the complication of Germany’s postwar situation — the debt, the sense of failure, the moral disintegration, the financial imbalance, the class warfare, the preponderance of mutilated victims — was rocket fuel for great art. George Grosz, Otto Dix, Max Beckmann, Käthe Kollwitz bombard us with scary picturings of the consequences of conflict. Dix, the show’s most uncomfortable presence, comes up with images so grotesque and transgressive, even in the Middle Ages that inspired them they would have felt as if they were going too far. A one-eyed soldier with half a face steps out with a scrawny whore. The picture is titled Two Victims. A skull on a battlefield overflows with writhing maggots. Sometimes the situation calls for neither dulce nor decorum, but for something much, much darker.

Aftermath, Tate Britain, London SW1, until Sept 23